Interview,

Sir George Benjamin on Lessons in Love and Violence

I can think of few works premiered within my lifetime which have had such a profound and immediate impact upon me as the operas of Sir George Benjamin: his first composition for the stage, the Pied Piper-inspired two-hander Into The Little Hill (2006), happened to be the very first piece of music theatre I ever reviewed, and the luminous, claustrophobic sound-worlds of Written On Skin (2012) and Lessons in Love and Violence (2018) mesmerised me to such an extent that I attended multiple performances of both works during their inaugural runs at the Royal Opera House and revisited them regularly when they appeared on DVD and Blu-ray.

I can think of few works premiered within my lifetime which have had such a profound and immediate impact upon me as the operas of Sir George Benjamin: his first composition for the stage, the Pied Piper-inspired two-hander Into The Little Hill (2006), happened to be the very first piece of music theatre I ever reviewed, and the luminous, claustrophobic sound-worlds of Written On Skin (2012) and Lessons in Love and Violence (2018) mesmerised me to such an extent that I attended multiple performances of both works during their inaugural runs at the Royal Opera House and revisited them regularly when they appeared on DVD and Blu-ray.

It was a great pleasure to meet up with Sir George in London recently to talk about the genesis of Lessons, the operas which have inspired and influenced him, and the evolution of his remarkable creative relationship with the playwright Martin Crimp (who has supplied the texts for all three of his operas to date).

You came to opera relatively recently, with Into the Little Hill receiving its first performance in 2006: did you deliberately hold off writing for the stage until that point in your career, or was it simply a case of the stars not aligning until then?

Both. I tried to write an opera when I was a child and must have written music for a dozen or so plays at school, so the theatre was absolutely in my blood. Then when I went to Paris to study, my musical concerns moved elsewhere, and they weren’t very compatible with music theatre. People were asking me for operas already in my mid-twenties, but I was constantly having to say no - at that stage I don’t think I was ready to collaborate with anybody, and (perhaps relatedly) despite dozens of meetings I didn’t find anybody with whom it felt right. But I always wanted to do opera, and over the decades I composed piece after piece (both with and without voice) which were preparations for writing one if the opportunity came along. I carried on meeting up with potential partners over the years, but it never, ever worked - in the end it was rather tiresome for them and for me, so I more or less gave up. Then a couple of years later I met Martin Crimp, and something just clicked.

How did that meeting come about?

I teach composition part-time at King’s College London, where one of my former colleagues is the very distinguished musicologist Laurence Dreyfus (who’s the founder of the viol consort Phantasm as well as being an exceptional musical thinker). Over lunch one day he casually mentioned that he knew a playwright who he thought was a genius, and engineered things in an extremely subtle, clever way so that when Martin and I met it was in the best possible conditions. Laurence was aware, I think, that nothing was guaranteed, but in the event it worked. There was sufficient difference between Martin and me - indeed at first our aesthetic concerns seemed rather far apart - but at the same time I sensed a mysterious imagination at work in this person, and a degree of integrity that I’ve rarely encountered. And I also liked him, which is actually not insignificant!

Tell me a little about how the collaborative process between the two of you plays out - do you work in isolation, or exchange ideas with one another as you write?

When we know that we’re going to do a project we talk for months: we read short stories, history, myth, all sorts of things, and start throwing ideas at each other. Martin’s very good at doing quick tests on projects: to write three pages doesn’t cost him very much, so for all three operas there have been quite a lot of attempts at getting something going which have been aborted when neither of us felt things were working. Eventually a subject just imposes itself, and the tendency then has been for Martin to simply disappear for nine months, and one day the complete text will arrive in the post. (I use the word ‘text’ advisedly, as Martin dislikes the word ‘libretto’ – he finds the ‘little book’ aspect patronising, as these projects are big undertakings for both of us).

I won’t start work until I have everything: I want to judge the scale, the pacing and the nature of the form according to the whole story. And then (at least in theory) I disappear for two and a half years and write the music, but the one thing that has changed over the course of our three projects together is that now I keep in touch with Martin and ask him questions as I compose. With Lessons I was quite regularly in contact, querying the placing of a word, or a character's motivation for a particular line; on the rare occasions when I ask a musical question he will always refuse to answer that, but he will give me psychological, structural and dramatic insight when I need it.

His texts tend to be very spare and economical…

Yes, and that suits me extremely well – if there’s too many words you can’t write an opera! Singing gobbles up words, and there needs to be breathing-space for orchestral passages too. The other thing which I love about Martin's texts is their ambiguity, which not only leaves room for me to subvert or twist my angle on the story in unexpected ways, but also means that the audience aren’t necessarily being told what to think and feel at every given moment. It’s no longer the nineteenth century, where good is good and bad is bad: Wagner tells you what to think and feel at every turn, and it’s magnificent, but it’s not right for today.

Do you workshop scenes during the compositional process, or work directly with your cast as you write?

No, not at all. What I do is to meet the singers before I start work, and get to know them by accompanying them in Lieder or operatic extracts, while taking notes about the specific characteristics of their voice. But I’m also extremely secretive while I’m writing: even opening up to the extent of being able to talk to Martin while I’m composing is something that would have been unimaginable for me even fifteen years ago.

All the same, I have learned to collaborate this last decade or so, and it is now something which I value immensely. To write an opera in two-and-a-half years is very fast for me if you know my usual rate of working; but composing a work that fills a whole evening is inevitably a long and isolated journey, and I don’t tend to venture far from here, beyond going for the odd walk whilst I'm turning over ideas in my head. I have people who look after me – I’ve a wonderful publisher, and a devoted agent – but no-one touches my music. It’s just me and my paper.

Which operatic composers (or specific operas) have exerted the strongest influence on your musical imagination?

I’ve grown up on opera, and I love it probably more than anything else in the creative world. I loved Strauss tone-poems when I was ten or eleven, and then I got to know Salome and Elektra and loved them too; then Wozzeck; then after studying with Messiaen Pélleas et Mélisande perhaps even more than any of those. (I must also mention Messiaen’s own Saint François d’Assise – that’s a very unconventional opera, and not the one I would write myself, but it’s nonetheless magnificent). Berlioz’s Damnation de Faust and Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov are also immensely dear to my heart and would both be very near to the top of any list of favourite operas, and of Wagner I would single out Meistersinger, Götterdämmerung, and Parsifal. And then there’s Janáček - particularly Káťa Kabanová, which I think is a perfect masterpiece, though I am also fond of Jenůfa and The Cunning Little Vixen.

Looking further back, I like Nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni very much, and Monteverdi’s Orfeo is marvellous; I’m not a great Handel fan, but when I hear it I’m always impressed by the superb vocal writing. Of French operas, I like Carmen a lot, and I love L’enfant et les sortilèges; I don’t really care for Verdi, though I do adore Falstaff. In terms of British operas I have great admiration for Billy Budd, and the two operas by my late friend Oliver Knussen [Where the Wild Things Are and Higglety Pigglety Pop!]; I also admire Harrison Birtwistle’s The Minotaur and Gawain, and Tippett’s The Midsummer Marriage and King Priam...

But if I really had to choose, my favourites would be Berg, Janáček and Debussy – perhaps with a special mention for Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi, which is so incredibly funny. But I try very much to maintain complete independence when I’m writing and don’t listen to other operas at all: I have my own sound which is very hard to imagine for me, so once I get into that world I almost avoid other music altogether. That’s rather sad, but it does mean that when I finish a big piece and go back to concerts and operas it’s really wonderful.

All three of your operas to date have drawn on medieval sources to some degree – coincidence, or is there something about this period which particularly attracts you in terms of the musical and dramatic opportunities which it opens up?

It was never a conscious decision, but it’s somehow where Martin’s and my instincts have led us. Certainly more epic, mystic stories have got me into the world of music theatre: for me as a composer, a story that feels relatively remote from the present day beckons music more readily than something that’s set fifty or even ten years ago. It says something that the majority of those operas which I mentioned as being special to me are set in the ancient or medieval world - and in fact if you look back to the very beginnings of opera, myth has always been closely associated with this unrealistic and in some ways rather strange art-form. Of course there are no hard and fast rules (from Figaro onwards there are operas of sheer genius which are set in the contemporary world), but perhaps the genre works most brilliantly when it doesn’t try to represent reality as it is lived from day to day.

One of the reasons I waited for so long to compose an opera was that I couldn’t imagine finding a way of writing that was authentic, that wasn’t ‘neo’ or ironic. But Martin’s particular way of writing, with its strangeness and artificiality masking incredibly strong powerful emotions and dramatic situations, is exactly what I needed, although it took me a long time to find it. Despite the source-material [the chronicles of Edward II], Martin and I didn’t want Lessons to be medieval (indeed Katie Mitchell’s production was set in an ultra-modern, chic Scandinavian castle), and in Written On Skin you had the contemporary world summoning the medieval story in a pseudo-realistic way – there was framing in the text as well, because of the self-narration that was involved, and without that framing I don’t think I’d have been able to write the piece. So in a sense, we’re trying to have our cake and eat it, because we set our stories in the far-distant past whilst consciously and very directly admitting that we’re telling them from today’s point of view. But who knows where we might go with that in the future?

Did you revise the score of Lessons much for the revival in Amsterdam?

I made no major changes to the substance of the music, which is normal for me – but I did make hundreds of minor changes regarding little details of tempi, notation, muting the strings or brass, and above all revising dynamics. I’m always very happy when other people conduct my work, but it’s good to be on the rostrum initially, because then I can experiment within the time-constraints and think ‘I really want that exceptionally low pedal B flat in the contrabass trombone to be heard, so I’m going to mark it up from one forte to four!’

Do you have plans to write more opera, or for future projects with Martin Crimp?

I very much hope so. I believe it’s extremely hard for composers to find a collaborator with whom they feel in harmony, and it’s by no means a foregone conclusion that someone’s writing in English will bring music out of me. I’ve been exploring some of the correspondence between composers and writers recently, and was profoundly touched by the letters between Richard Strauss and Stefan Zweig, the Jewish novelist who supplied the text for Die schweigsame Frau. Zweig was already falling victim to anti-Semitic laws in Nazi Germany by this point, and he told Strauss that their association would harm Strauss’s reputation, that it was simply impossible to mount any work that they wrote together in Germany at that time. Strauss wrote him numerous pleading letters, even going so far as to say ‘If you don’t collaborate with me again, the composer Richard Strauss is finished’. He did eventually find other people to write with, of course - but as with Hofmannsthal beforehand, he valued this relationship immensely, and that certainly resonated with me. Composing has always been difficult for me, but there’s something about a page of Martin’s words which galvanises me like an electric shock. So I think the answer is very simply ‘Yes’.

Stéphane Degout (King), Barbara Hannigan (Isabel), Gyula Orendt (Gaveston/Stranger), Peter Hoare (Mortimer), Samuel Boden (Boy/Young King)

Orchestra of The Royal Opera House, George Benjamin, Katie Mitchell

Available Format: DVD Video

Stéphane Degout (King), Barbara Hannigan (Isabel), Gyula Orendt (Gaveston/Stranger), Peter Hoare (Mortimer), Samuel Boden (Boy/Young King)

Orchestra of The Royal Opera House, George Benjamin, Katie Mitchell

Available Format: Blu-ray

Vocal score

Available Format: Sheet Music

Christopher Purves (The Protector), Barbara Hannigan (Agnès), Bejun Mehta (First Angel/Boy), Victoria Simmonds (Second Angel/Marie), Allan Clayton (Third Angel/John), Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano)

Mahler Chamber Orchestra, George Benjamin

Available Formats: 2 CDs, MP3, FLAC

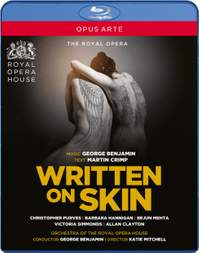

Christopher Purves (Protector), Barbara Hannigan (Agnès), Bejun Mehta (First Angel/Boy), Victoria Simmonds (Second Angel/Marie) & Allan Clayton (Third Angel/John)

Royal Opera Chorus & Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, George Benjamin (conductor) & Katie Mitchell (director)

Available Format: DVD Video

Christopher Purves (Protector), Barbara Hannigan (Agnès), Bejun Mehta (First Angel/Boy), Victoria Simmonds (Second Angel/Marie) & Allan Clayton (Third Angel/John)

Royal Opera Chorus & Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, George Benjamin (conductor) & Katie Mitchell (director)

Available Format: Blu-ray

Hila Pitmann (soprano), Susan Bickley (contralto), London Sinfonietta, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, George Benjamin

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC