Interview,

Vasily Petrenko on Rimsky-Korsakov

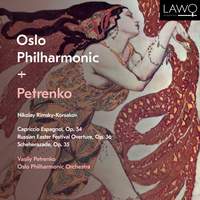

It’s always a privilege to gain insights on a Recording of the Week from source, and for today’s Rimsky-Korsakov triptych from the Oslo Philharmonic I went directly to the horse’s mouth (thanks to our friends at IMG and Valerie Barber PR) in the form of Russian conductor Vasily Petrenko, who’s poised to depart Oslo before taking up a new position with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra later this year. We spoke at the end of last month about his contingency-plans for music-making after lockdown, his upcoming recordings from Oslo and Liverpool, and the special challenges which Scheherazade presents to both conductor and orchestra.

It’s always a privilege to gain insights on a Recording of the Week from source, and for today’s Rimsky-Korsakov triptych from the Oslo Philharmonic I went directly to the horse’s mouth (thanks to our friends at IMG and Valerie Barber PR) in the form of Russian conductor Vasily Petrenko, who’s poised to depart Oslo before taking up a new position with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra later this year. We spoke at the end of last month about his contingency-plans for music-making after lockdown, his upcoming recordings from Oslo and Liverpool, and the special challenges which Scheherazade presents to both conductor and orchestra.

Where and how are you spending lockdown?

I’m in Liverpool, and will be for the foreseeable future. I’ve got plenty of different things to be getting on with: as well as revising scores there are various upcoming releases of recordings with both Oslo and Liverpool to be edited, and I’ve also started a series of lockdown talks with key people from the most affected industries, such as Simon Reinink who manages the Concertgebouw building. One possibility I’m keen to explore is the idea of introducing temperature-checks in major venues, as is happening in airports, to reduce risk for players and audiences…Aside from that, I’m growing tomatoes - and my beard!

What’s the repertoire on those upcoming releases?

From Liverpool we have Petrushka and Respighi’s La Boutique fantasque coming out first, followed by Zemlinsky’s Die Seejungfrau. After that there will be two pairings of Prokofiev and Myaskovsky from Oslo, on LAWO: Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5 and Myaskovsky 21, and Prokofiev 6 and Myaskovsky 27. The two composers were friends and almost direct contemporaries, and each pair was written in the same year but they have very different approaches. Myaskovsky wrote 27 symphonies, and some of them are incredible; 21 is a short work, but a very powerful one. He was actually a pupil of Rimsky-Korsakov; he grew up in the age of ‘The Glorious Russia’, and because of that I think his music has less edge, less terror than you see in later composers like Shostakovich.

What are the main challenges of Scheherazade for you?

First and foremost, the beginning and the end! Those opening and closing sequences of chords (which are almost identical) are notoriously challenging and difficult to tune: obviously in recordings you get a few chances, but in concert it’s one of those moments where most conductors just pray! It’s very challenging for each individual instrument to find the right tone, and it’s so transparent and exposed that even if you adjust very quickly it’s already too late. And there needs to be a micro-caesura between each chord, so ending each one is also tricky. Those chord sequences set the mood for the whole piece and also calm all of the turbulence and storm at the very end, where it’s almost like a transfiguration. And of course at the end the solo violin is also involved. As I said to the orchestra in rehearsals, it always feels to me that when the Sultan releases Scheherazade and she’s free to return to her homeland she still feels a certain sorrow, because those 1001 nights were probably the most intense and dramatic in her life; there’s a sense of nostalgia, not just about where she goes back to but also about what she’s leaving behind.

In the first movement the challenge to me was to create a real sense of the sea and the waves – and that’s where you have to insist on this famous ‘Russian sound’ from all the strings, not least in the accompaniment. The difficulty is that the opening is very repetitive, particularly for the cellos and basses who are essentially playing the same arpeggios for a couple of minutes, and I like them to think of themselves as the pilot who’s steering the ship: every bar needs to have interest and direction, as if you’re ploughing into each individual wave and leaning back out. That’s exhausting, especially in a recording where you have to insist that each take has the same intensity, but it’s essential to set the scene for this story about a sea journey that’s coming up.

In the second movement there are so many interconnected solos, often coming from different sides of the stage (and maybe in our socially-distanced future that will be even further apart!); my job is to predict when one solo will finish and figure out how to pass it to the next player. The idea of story-telling is especially important in the middle two movements, and in the third one you need to find enough natural momentum to keep the narrative flowing but not rushed: that will allow you to tell the story of the Prince and Princess without making it into some slow, grand epic. It has to unfold like a fairy-tale, not a Dickens novel!

The finale is not an easy movement for me or the players – the writing is so virtuosic, and as a conductor you mustn’t be in the position of trying to close the stable door after the horse has bolted! Orchestras everywhere have a tendency to rush here, because of the way it’s written: they see pages of demi-semiquavers and think they need to play faster than they actually do. You need to pace it just right so that you don’t lose the very special effects which Rimsky-Korsakov deploys: using the trombones and percussion together, having the strings playing one of the Shahryar melodies with all downbows on the G-string…all of that requires your attention. But probably the most difficult thing is how you approach the shipwreck. It’s very tempting (and very easy) to play too loud too early, which means you lose the sense of the climax when the ship crashes into the cliffs. I won’t name names, but sometimes when I’ve watched live performances it’s felt like conductor and orchestra were in constant competition as to who can get there faster!

You touched earlier on one element of the fabled ‘Russian sound’ – what are its other key ‘ingredients’?

As well as getting the upper strings to embrace the G-string colour, I think another of the characteristics is paying attention to the centre of the note: the middle of the bow-stroke has to have the same intensity as the initial attack and the end, and that also has to be matched in the left hand. It’s challenging to do this with any orchestra, because again it’s so physically tiring. The fundamental difference with Russian orchestras is that most of the string-players are trained as soloists: the conservatoires are busily preparing new Oistrakhs or Kogans or Slavas, and it’s only perhaps within the last five years or so that they’ve started to create education programmes specifically for future orchestral players. Of course because very few of them made it as soloists they ended up sitting in a string-section where every single player can absolutely nail their Tchaikovsky concertos. The difficulty for a conductor is how to gel fourteen or sixteen players who each has a very distinctive timbre, as well as their own strong opinion about how to play the music (which they generally aren’t afraid to express to their colleagues, or to you)! But if you can find a way to bring unity to a section like that then the depth and richness of the sound is incredible.

What are your personal highlights from your time in Oslo?

So many things! But the various cycles we did together stand out: it was very important to me to make a contribution to Scriabin, whose music deserves so much wider recognition. He was constantly in search of novelties throughout his short life, not only in terms of the relationships between music and colour but also in his harmonic language; it’s astonishing to see how he went from the very classical approach of his First Symphony to what he does in Prometheus, where the language is still tonal but completely non-classical.

Our cycle of the Strauss tone-poems (almost all of them!) was also special: that happened relatively late in my tenure, and I was so proud of what the orchestra achieved there in terms of textures and vividness, and also of how magnificent they could sound in the rather challenging acoustic of the Oslo Concert Hall. There were a lot of celebrations around the orchestra’s centenary last year, but what could have been one of the most memorable concerts was sadly something that didn’t happen – I was supposed to finish there last month with Mahler’s arrangement of Beethoven 9, which fell victim to lockdown. But we plan to maintain a close relationship: I have at least two programmes scheduled for 2021, and I’ll be returning every year for the foreseeable future.

I’ve yet to meet my successor, Klaus Mäkelä – Chief Conductors have never been involved in the appointment of their replacement in Oslo - but I think he’s a very bright emerging talent, and there’s great potential in the collaboration. They were specifically looking for someone in that age-bracket, someone with a fresh and different approach; there will be a bit of a generation-shift in the orchestra over the next couple of years, with various players retiring and new replacements coming in, so it’s a good time for them to grow together with a young new conductor.

Could you expand a bit on the challenging Oslo acoustic?

The main issue is the shape of the back of the stage. There’s no wall behind the brass and percussion: they have quite a massive space behind them, so they don’t hear enough from the front of the orchestra, which naturally provokes them to play louder. And there’s also the difficulty of playing together: because the hall is basically a rectangle, the sound travels around and bounces from the walls several times, and again that affects the players at the back of the stage because the string sound reaches them a little late. I think over the years we all learned where the downbeat should be, but at the beginning it was a challenge!

The auditorium, too, has its quirks: the sound on the platform (anywhere on the platform) is so different from what you hear out in the hall, and the left side is also very different from the right. Over the years I spent a lot of time listening to other people’s concerts, or just walking around the hall while we were rehearsing; they can play without you for a while (!), and you can use that time to explore the sound in the auditorium. It’s nearly impossible to find a good balance for everyone, so you have to compromise and find something that works for the majority of the audience and players.

Audience comfort is another issue. It’s a very wide hall, and the auditorium isn’t curved - so if you sit in the corner and want to look towards the centre (as most people naturally do) you have to keep your head turned, and it’s not really comfortable to sit like that for an entire symphony! I’ve been campaigning for a new concert-hall in Oslo for years (as Mariss Jansons did before me), but with the world headed for an economic recession I don’t know how much budget there will be, even in a comparatively rich country like Norway. But I’d love a new hall to be built in Oslo, and their relatively new opera-house is a great example: it’s an incredible building which has become a tourist destination in its own right as well as taking the opera company itself to very different heights.

What’s coming up in terms of your move from Liverpool to the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra?

We announced my last season in Liverpool on Zoom, and ended up with the maximum 400 attendees! One of the highlights should be Mahler Eight at the Albert Hall in October, which is a joint project between the RLPO, the RPO, and four major choirs. It’s a glorious prospect, and a very fitting piece to do in that venue - but of course we’re all planning in the dark at the moment, so we have a Plan B and a Plan C depending on how many people are allowed in the hall, what kind of social distancing will be in place, and whether there will be a vaccine or tracing by then…With the RPO I’m planning Mahler symphonies and then a focus on British music the following season, alongside more standard repertoire at the Festival Hall. But perhaps we’ll have to do more chamber concerts rather than big symphonic works…it all depends on where the world’s going!

Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, Vasily Petrenko

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC, Hi-Res+ FLAC

Vasily Petrenko & Oslo Philharmonic Scriabin Series

Vasily Petrenko & Oslo Philharmonic Scriabin Series

'Petrenko is the ideal interpreter for this ripe overheated music…The Oslo Philharmonic responds with brilliantly incisive ensemble' (BBC Music Magazine on Symphony No. 2 and the Piano Concerto)

Vasily Petrenko & Oslo Philharmonic Strauss Series

Vasily Petrenko & Oslo Philharmonic Strauss Series

'As Petrenko’s tenure in Oslo begins to wind down, he revels in the standards of orchestral virtuosity he has attained with this excellent band in two Strauss tone poems that challenge all instrumental departments...the Osloers shine brilliantly' (The Times on Also Sprach Zarathustra & Ein Heldenleben)