Interview,

Ruby Hughes on Clytemnestra

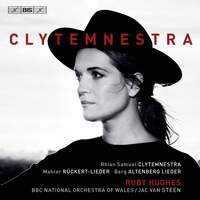

Released on BIS at the end of January, the British soprano Ruby Hughes’s first solo album with orchestra for the label takes its title from a remarkable monodrama by Welsh composer Rhian Samuel, which was written for Della Jones in 1994 and receives its world premiere recording here; setting the composer’s own adaptation of text from Aeschylus’s Oresteia, the piece depicts Clytemnestra’s murder of her husband Agamemnon on his return from the Trojan War, ten years after his sacrifice of their daughter Iphigenia in order to placate the goddess Artemis on the journey to Troy.

Released on BIS at the end of January, the British soprano Ruby Hughes’s first solo album with orchestra for the label takes its title from a remarkable monodrama by Welsh composer Rhian Samuel, which was written for Della Jones in 1994 and receives its world premiere recording here; setting the composer’s own adaptation of text from Aeschylus’s Oresteia, the piece depicts Clytemnestra’s murder of her husband Agamemnon on his return from the Trojan War, ten years after his sacrifice of their daughter Iphigenia in order to placate the goddess Artemis on the journey to Troy.

Ruby and I spoke recently about Samuel’s vivid depiction of one of Greek mythology’s most complex and conflicted characters, and the relationship between the piece and the two song-cycles by Berg and Mahler which are also featured on the album.

In comparison with other strong women from mythology, Clytemnestra’s been given relatively short shrift by composers over the centuries – why do you think this is, and how is her story structured in this piece?

I have no idea why more composers haven’t been inspired by her, because she’s such a fascinating character - Strauss gives her a fantastic scene in Elektra, but that’s about it! It would be wonderful if one day Rhian might be commissioned to write an opera about the myth.

At the beginning of the piece she’s waiting for Agamemnon to come back, lamenting his absence and watching out for the beacons that have been lit on top of the mountain to signal his return. When he eventually appears she’s delighted to see him, but she’s also mourning the death of their daughter: she’s very emotionally conflicted, because on the one hand she still loves him but she also can’t bear the fact that he's sacrificed Iphigenia, so it’s a truly tragic situation. The orchestra depicts him riding back in state on his chariot, and the music's full of pomp and a sense of occasion – but underneath all of that you can feel her barely suppressed anger. She’s probably quite alienated from him, even leaving aside the terrible act he's committed: in Aeschylus's story he’s the all-conquering, celebrated warrior and it feels as if she’s trapped in a hierarchical, patriarchal society where perhaps women have very little power.

Rhian’s structured the piece so that Agamemnon’s return leads attacca into ‘The Deed’, which to me suggests that the murder is quite a spontaneous thing. The voice drops out altogether here, and it’s depicted in a fairly short orchestral section which is extremely dramatic and horrific – there’s a lot of percussion involved, and the strings and wind and brass are all going hell-for-leather. Rhian also adds an electric guitar to the mix at this point, so you get the really high piccolo and flutes set against the very low twangy electric bass, which for me symbolises the net which she uses to strangle him. The decision to leave The Deed to the orchestra works brilliantly on several levels: it’s so gruesome that anybody singing at that point would detract from the action, and also if the piece was staged operatically it would work very powerfully for Clytemnestra to be in action rather than singing.

The following section is called ‘Confession’, where Clytemnestra sings about what has passed, and it’s pretty devastating: she says ‘It was all words, careful words, and I unsay them all through what I’ve done/I wove the net of doom for my darling, my king’, so here we get a clear sense that she still loves him despite what she’s done.

And though she doesn't actually sing during The Deed, the retrospective description of the murder is fairly explicit...Do you feel that there's any intersection of sex and violence here?

She talks in quite graphic detail about how his blood spattered her like dew – in a way it’s a bit like Handel’s Brockes-Passion which I recently recorded, which is not only a reflection on the Passion of Christ but also of the civil war in Germany that was happening shortly before the text was written. It doesn’t hold back on the violent imagery, and in that respect Clytemnestra is similar – Aeschylus’s text is very visceral and it doesn’t leave much to the imagination! But I don’t feel that there’s any sort of Freudian element, where sex and violence are intertwined: we know she’s been apart from her husband for many years, but to me she’s motivated by utter desolation and revenge. (If anything I'd imagine she'd feel repelled by any sexual advances from him, and perhaps that could even be what prompts the murder). Even ‘revenge’ doesn’t feel like the appropriate word, because she acts out of sheer desperation rather than getting any kind of thrill or satisfaction from The Deed. She probably doesn’t know how to live with him any more in the knowledge of what he’s done.

Did you have much direct dialogue with the composer while you were working on the piece?

Yes, we had a lot of contact – she was really very proactive and fantastically helpful. The first time I heard about the piece was while I was a New Generation Artist at the BBC and Tim Thorne who was a producer there asked me if I’d be interested in performing it; he told me a bit about the history, that it’d been premiered by Della Jones in the 1990s and then lay dormant for the best part of twenty years. I looked at the score and thought it was absolutely fascinating, but it took me a while to decide to do it because it really pushed me out of my comfort-zone; it felt like it was within my capabilities range-wise, but it’s sometimes really exposed and very virtuosic.

Once I’d agreed to take it on, though, I didn’t look back: I was lucky enough to have three or four months to really work on it technically, and I had both the vocal line and a piano reduction recorded separately so that I could learn it very precisely. I also studied it a lot at the piano myself, just getting the vocal line really ingrained into the body – and once you’ve got Rhian’s music sung in, it really does stay put! She has her own unique harmonic language which includes some twelve-tone elements but is essentially tonal, and because of that it feels ‘sung in’ quite quickly - unlike some very cerebral contemporary music which you can study for months on end and still need to count furiously and stare at the score! Before the recording we did one concert in Bangor, and I absolutely loved performing something so direct and visceral: it paints an incredibly vivid picture of her as a very vulnerable woman as well as a powerful one.

Do you feel any stylistic affinity between Rhian's musical language and the Berg and Mahler song-cycles on the album?

I spoke to Rhian in quite a lot of detail about her inspiration and which composers she particularly loved, and she talked a great deal about Berg and the Second Viennese School and how much influence that had had on her, as well as her love for Mahler. I’ve always been a huge Mahler and Berg fan too; before we made this recording I’d performed both of these cycles with the BBC Philharmonic and knew I loved them. The Altenberg-Lieder in particular have something very special about them, because they’re so pivotal to twentieth-century music in that they form a bridge between late Romanticism and serialism. I feel Berg has a way of navigating that which is very unique: he still keeps one foot in the world of late Romanticism even as he dabbles in twelve-tone techniques, and for me that balance of heart and head is absolutely perfect. The way he orchestrates around the voice also reminds me very much of both Mahler and Rhian; as I was learning Clytemnestra I saw very clearly how Rhian has looked to Berg and Mahler for inspiration in terms of balancing massive orchestral textures with passages where everything is pared right down, and it results in some quite extraordinary colours.

It’s also somehow bound up in folk music, and even very early opera: the dirge at the end of the piece has a power that has echoes of a lament like Dido's in that on paper it’s incredibly simple, but it has a directness that makes your hair stand on end.

You've made a point of incorporating music by living composers on your recordings for BIS - can you divulge anything about your plans on this front?

I love championing contemporary music and I've collaborated with Helen Grime and Huw Watkins alike. Helen is currently writing me a piece for string orchestra and voice, which will be premiered in 2021 – I think the working title is Songs of Joy, but I don’t know too much more about it at the moment. She also wrote me and Joseph Middleton a beautiful cycle called Bright Travellers a couple of years ago, which is all about new life and pregnancy and birth; Joe and I have already recorded that for BIS, and it’s coming out in January 2021.

Ruby Hughes (soprano), BBC National Orchestra of Wales, Jac van Steen

Available Formats: SACD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC