Video Interview,

Joyce DiDonato on EDEN

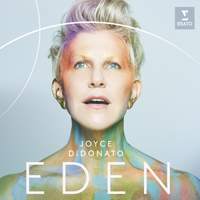

Featuring music by composers including Ives, Cavalli, Handel, Gluck and Wagner (plus a new commission by Rachel Portman), Joyce DiDonato's eclectic new concept-album with Il Pomo d'Oro constitutes what the American mezzo describes as 'an invitation to return to our roots', and is supported by an international education programme which aims to inspire participants to 'plant seeds of hope for the future'.

Featuring music by composers including Ives, Cavalli, Handel, Gluck and Wagner (plus a new commission by Rachel Portman), Joyce DiDonato's eclectic new concept-album with Il Pomo d'Oro constitutes what the American mezzo describes as 'an invitation to return to our roots', and is supported by an international education programme which aims to inspire participants to 'plant seeds of hope for the future'.

During a break from rehearsals for the inaugural concert of the EDEN tour last Thursday, Joyce joined me via video-call from her dressing-room in Brussels to discuss the genesis of the project, how she finds time and space to connect with nature amid her busy performance-schedule, the many and varied perspectives on the natural world which feature on the programme, and the joy of collaborating with composer Rachel Portman and poet Gene Scheer on The First Morning of the World (which she commissioned specially for the project).

Due to a mid-interview Zoom malfunction at our end, we unfortunately have no video-footage of the second part of the conversation in which Joyce answered a selection of questions submitted by Presto readers - however, we've provided a transcript of her responses below. which we hope is some consolation! Many thanks to all who responded, and apologies that time didn't allow for us to incorporate all submissions!.

'The EDEN engagement is fantastic and I would love to get involved. I'm a university teacher, but unfortunately not an artist. How can non-artists get involved?' (from Kristina Maul)

Thanks for the question – this is a really exciting element of EDEN which is going to evolve as the project goes on. We already have our EDEN website up and running, and on that we’re going to start listing curriculum that’s being done in the workshops and the engagement elements of each city: we have ‘Root’ cities with deep-dive workshops, and ‘Seed’ cities with one-day workshops. We’re looking to develop curriculum as we go along, and the idea is that this can be implemented by anyone across the world: you can take some of the ideas and develop your own. ITAC [International Teaching Artists Collaborative] are our Education & Engagement partners on this, and they are always looking for great educators to contribute and participate, so checking out connections with them is another avenue to explore.

'What are some personal choices that you have made, saying “I would love to use/enjoy that, but my EDEN conscience/consciousness will not let me do it…”?' (Anonymous)

It’s all about making little changes and doing the best that we can. I can’t drink bottled water any more: I have a fantastic water-bottle that was given to us at the Edinburgh festival a few years ago, and that’s my go-to. I also found a shoe line called VIVAIA, who make the cutest washable ballet-flats from recycled material; that may not sound very glamorous, but they’re super-comfortable and I’ve never been known for my footwear anyway! And one of the things we’re looking at with EDEN is using different routings for the tour, taking much more ground transportation than we have in the past as opposed to air travel.

’One of the pieces on the new album is “As With Rosy Steps” from Theodora. For many music-lovers, the music is inextricably associated with the haunting voice and incendiary interpretation of Lorraine Hunt Lieberson. How do you work to bring your own feeling and phrasing to pieces where the shadow of great predecessors looms large?’ (from David Jones)

That is such a good question. I’ve actually spoken about this with a lot of my mezzo colleagues, and so many people said ‘No, no, I would never sing that role!’. Lorraine Hunt Lieberson’s Irene in that production was such an epic combination of artist, role and moment: I think probably in the top five incarnations of any artist and role ever, certainly in our times. I’m not sure I would have had the courage to do it, say, ten years ago: I think this role came at just the right time for me. As opera-singers we’re always competing against the ghosts of the past in a way: you don’t sing Mahler and not have the ghost of all those great interpreters behind you. Or Mozart - I remember reaching out to Frederica von Stade when I was starting to do Cherubino and saying ‘Flicka, I can’t do it: this is YOUR role!’. Her reply was ‘Oh hon, just have fun with it!’.

So it’s a challenge for every role, but this one in particular is so revered, and in my opinion rightly so. The way I worked through it was to put myself in Miss Hunt Lieberson’s position: I never had the pleasure of meeting her in person, but I heard she was all about the art, and I couldn’t imagine a scenario where she wouldn’t want this piece to continue to be heard and experienced. I think she’s somebody who clearly connected to it in a really profound way; I am convinced that she would have wanted it to reach as many people as possible, and in order for that to happen it needs to continue to be performed.

And so that’s the place that I came from – I listened to the Glyndebourne recording, and I saw the video of ‘As with rosy steps’, but then I realised that I couldn’t watch the whole video. So I’ve never seen the Glyndebourne production of Theodora, because I’m a bit of a chameleon and I knew I would take on characteristics unconsciously. Instead I thought ‘I’m going to trust the power of the piece – I’m going to trust my experience and my connection to the role, and I’m going to approach it where I am at this moment in time, and I’m going to do as much honour and justice to it as I can’. That’s how I got through it, but it wasn’t easy!

'As a ballet student I have often heard criticisms framed as "tough love". How do you distinguish between criticism that is constructive and criticism that is destructive?' (from Jutta)

My heart just pours out to people asking that and living that challenge, because it is a real challenge. Part of the deal of going into the performing arts is that you make a pact that you’re going to be open to constant criticism and scrutiny. When you’re a student it comes from your instructors, it comes from your colleagues, and it comes from your competition; then if you’re lucky it starts to come from an audience and from critics, and even if you go on and you live your dream of performing on the world’s great stages you’re still under constant criticism in this industry.

The real work – and it’s hard, it’s demanding, it’s gut-wrenching and it’s excruciating, but it can also be liberating – is that you have to find a way to remove the emotion from the feedback. Feel the emotion, have a good cry, then get back to work like you’re the CEO of your business: become a little bit detached, not in your attitude to performance but in your response to criticism. Formulate it like you’re the CEO of Apple and you need to look at the bottom line and say ‘Give me the truth: how are sales? What are the figures looking like? What’s the problem with that model?’. We need the truth, and we need real feedback to show us how to improve, how to break through things that are limiting us and limiting our expression - and we have to realise that it's not personal.

So through discernment, start to figure out who really knows what they’re talking about and who’s trying to get under your skin for other reasons - that’s important to know. You need to find people that you can trust: take those difficult things to hear on board, then work on them and use the experience to become better.

At the same time, the other work that you need to be doing is to be constantly coming back to why you’re putting yourself out there and what it is that you want to say, and for that to become your highest priority. If your highest priority is: ‘Do they like me? Am I good enough?’, then you’re never, ever going to have satisfaction. You’re always going to be disappointed, and always going to be chasing somebody else’s approval – that’s exhausting, and it keeps you from being your own authentic real artist. Look at the great artists that you admire, and I would bet that 10 times out of 10 they’re being true to who they really are. So while you’re incorporating all of this feedback and criticism and information, I think your real work is to discern who you truly are as an artist and how to get that message out clearly into the world.

'Is it more difficult to be on the road again after staying in your house during the Great Pause?’ (from Annamieke)

It’s a big question, and I hesitate a little bit to answer, because I think the reality that artists are facing right now is brutal – and I don’t like to dwell too much on the brutal things in life! It’s so much harder now, and it’s always been challenging to be on your own away from home, to be under that constant scrutiny and critical eye. I don’t talk too much about it, because I figure that’s part of what I signed up for: I put myself in that position, and every job has its pros and cons. But the truth is – and I experienced this a lot in London recently – that when you look around and everybody’s singing rehearsals with the most uncomfortable masks, breathing and all of that equilibrium of using our body is destroyed. It’s necessary, but we can’t pretend it’s not disruptive. And travel right now is very challenging too: there’s a lot of anxiety that comes into play around the constant testing.

I don’t think there’s ever been a more critical time for the world to continue to cultivate the arts – it’s been devastating to feel how the arts have been viewed as disposable, but also as the one thing that people have really turned to (and have expected to get for free). Artists produced so much content over these last two years because we had to - having that expressive vehicle removed from us and having it all stuck inside and not having an outlet at such an acute time had deep effects on so many artists that I know. It feels like artists were required to put themselves on the front lines, but without the recognition from society at large: we were expected to produce but we weren’t supported, and that’s taken a lot of toll on a lot of people. And yet here we are, because it’s in us: we have to do it.

Joyce DiDonato (mezzo), Il Pomo d'Oro, Maxim Emelyanychev

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC