Interview,

Franco Fagioli on Adriano in Siria

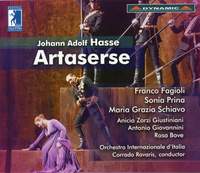

Over the past couple of years the stupendous technique of 'heldencountertenor' Franco Fagioli has played no small role in the resurrection of previously neglected operas written as showcases for the great castrati Farinelli and Caffarelli. To date, he's recorded compelling accounts of the villainous Medarse in Hasse's Il Siroe Re di Persia, Arbace in Vinci's Catone in Utica (both of these for Decca), and the character of the same name (it's a popular one in early eighteenth-century opera!) in two settings of Metastasio's Artaserse: Vinci's version on Virgin and Hasse's on Dynamic, released earlier this year. Now it's the turn of Pergolesi's Adriano in Siria, written just two years before the composer's untimely death at the age of 26 - the recording, released last month on Decca, was one of our Top 100 Discs of the Year.

Over the past couple of years the stupendous technique of 'heldencountertenor' Franco Fagioli has played no small role in the resurrection of previously neglected operas written as showcases for the great castrati Farinelli and Caffarelli. To date, he's recorded compelling accounts of the villainous Medarse in Hasse's Il Siroe Re di Persia, Arbace in Vinci's Catone in Utica (both of these for Decca), and the character of the same name (it's a popular one in early eighteenth-century opera!) in two settings of Metastasio's Artaserse: Vinci's version on Virgin and Hasse's on Dynamic, released earlier this year. Now it's the turn of Pergolesi's Adriano in Siria, written just two years before the composer's untimely death at the age of 26 - the recording, released last month on Decca, was one of our Top 100 Discs of the Year.

Ahead of his concert performances of the opera with Parnassus Arts (the brainchild of his fellow countertenor Max Emanuel Cencic, the company's provided much of the impetus behind getting these works back on stage after centuries in obscurity) in Paris and Vienna, I spoke to Franco over the phone last week to discover more about the opera's salient features, his approach to baroque performance-practice, and his affinity with music written for the notorious star castrato Gaetano 'Caffarelli' Majorano: he's every bit as animated and expressive in conversation as he is in performance...!

Tell me a little about your character in Adriano in Siria, the journey that he takes, the musical challenges...

The part I’m singing is the prince Farnaspe – it’s a heroic role, and as we all know, all good baroque heroes are about suffering and about loving, about trying to pursue all the virtues at the same time! And the role was composed for a very crucial figure, Caffarelli (the great castrato who was the subject of one of my recent solo CDs), so let’s say Farnaspe is one of those typical Caffarelli heroes, pursuing love and virtue. There’s no dark side to him at all, really - he’s like a lot of the Romantic tenors!

And one of the arias from Adriano actually appears on that Caffarelli discs, I think…?

Yes, ‘Lieto cosi talvolta’, which is a very beautiful cantabile aria with oboe obbligato; it comes at a crucial moment in the opera, in the middle, when Farnaspe expresses all these emotions using the metaphor of the nightingale [represented by the oboe]. Now Adriano is not like many Baroque operas in which the main characters have lots and lots of arias: Pergolesi wrote just three arias for Caffarelli, but all of them are incredibly demanding and I think what makes this aria so memorable is that combination of beauty and technical difficulty (it has very long phrases as well as a very expansive register, going from a D to high B natural, so it’s very challenging to sing). We could compare Farnaspe’s music in this opera to a sonata in which the first aria/movement is fast and florid, the middle is one very slow and beautiful, and the last aria is also another fast one.

The opera’s a treasure-trove of virtuoso arias, but what really stuck out for me is that beautiful duet you have with Emirena (Romina Basso) towards the very end…

It’s indeed very beautiful, and the interesting thing about this duet (and duets in general are not heard that often in Baroque opera!) is that the male character (as never before, possibly?) is singing above the female character; that’s because the part of Emirena was written for a female alto and the part of Farnaspe was of course written for Caffarelli, who had a soprano range. This again is very demanding for me because I have to be in a quite high tessitura, but it’s a such a great effect to throw in towards the end of the opera, because it’s so unexpected!

As you mentioned earlier, you sing a lot of the music written for Caffarelli and have done a great deal over the past couple of years to put him 'on the map': do you feel a strong connection to his repertoire in particular?

Caffarelli and I first 'met' ten years ago when I did a lot of research about him and about the operas that were composed for him, because I was preparing this homage to him for the recording. Until I recorded some of these Caffarelli arias there was not much about this singer on the market - there was lots about Farinelli, or Carestini, or Senesino, but not Caffarelli. The thing with Caffarelli is that it seems he was a supremely talented singer with really extreme technical abilities – the music that was written for him is always so very demanding, but even though it’s so challenging I think it’s such a good fit for my voice, so it was more about feeling that technical connection rather than a more emotional or personal one! But I certainly feel a great deal of respect towards him: he seems to have been a very great singer…there’s an anecdote that his tutor, the great singing-teacher and composer Nicola Porpora (who was the subject of another of my solo CDs), told him he had nothing left to teach him! So ultimately my relationship with him is about respect and about learning something more each time I’m preparing to perform an aria that was written for him, because I think it's honestly some of the most difficult music I’ve ever seen – the operatic arias in particular are extremely taxing!

Am I right in thinking that Farnaspe's music sits particularly high, even for a role written for Caffarelli?

Yes, absolutely! He has a very, very expansive register from low notes to high notes: in this opera you are singing a lot of high Bs, but at the same time after you sing the high B, you go directly to sing a B in the lower register – two-octave jumps. It’s really extreme writing for the voice, I must say. For me it’s challenging, but it’s so good to do it, because you learn how to really manage your instrument

What's your approach to ornamentation and cadenzas? Do you research what the castrati themselves might have done, write your own material, collaborate with the musical director on the project...or is it a combination of all of these things?

Ornamentation is a mix of many little details. Of course we read a lot, and learn a lot about how castrati used to ornament it themselves, and we also know that they were fully prepared musicians - not only about singing technique, but also about harmony and theory and about playing an instrument. Before I became a singer I did a lot of piano studies: I was very fond of it, and I must say it’s a very good background when you first become a singer. In my case, what I do is try to get knowledge about how they used to practice in Baroque times, and after that I take my turn! I have to do the ornamentation that will work with my voice, of course, but then after that I’m still very concerned with the ornamentation tuning into the emotion in the aria. Of course, we are performing music that was written several centuries ago, but at the same time I try to do something in between acknowledging historic performance and also recognising that we are in the twenty-first century – we are performers of today, so personally I don’t feel obligated to do ornamentation all the time if there isn’t an emotional reason to do it.

One of my inspirations for ornamentation is to serve the text, to serve the lyrics, but also to serve the emotional moment: it has to happen from inside of you, otherwise it looks very artificial and that’s not my idea of ornamentation. You must create an effect so that people that listen to you, so that when you sing that word or phrase or melody for the second time, you’re recreating that text for the audience. That’s why, for me, ornamentation always happens at the end of the process: especially when you are doing a staged performance of an opera, the ornamentations are related to what’s happening dramatically. You start it, you sing it many times and then you start to find the mood of the aria, the emotions that are going through the characters at the time - so that, for me, is what produces the magic and the inspiration needed to write ornamentation. Then, of course, in the context of live stagings, you can always improvise further...

There are over sixty settings of this particular libretto by Metastasio: what do you think made it so attractive to so many composers, over a period of 150 years?

Personally, I can’t say that I find anything really special in this libretto: it certainly sticks to the theatrical conventions that you can see all the time in operas of this period, which may have made it make it especially convenient for Pergolesi, because he was a composer who was very prolific in a very short time. But what I do see here is this attraction of a libretto in which the main character, the loving hero, is not the title-character (in this case Adriano’s actually is a bit of a bad guy!) – it’s the same situation in Artaserse, which is really all about Arbace! Later on it’s the other way around: the operas are named after the the hero, the character who is suffering.

Pergolesi's Adriano in Siria, with Capella Cracoviensis directed by Jan Tomasz Adamus, was released on Decca last month.

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

You can view Franco Fagioli's complete available discography here.

Recordings referenced in this interview

'It's a jaw-dropping disc. Fagioli is one of today's great vocal technicians, and the ease and almost superhuman agility with which he attacks some of the big bravura numbers are simply staggering.' (The Guardian).

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

'Fagioli forges his own powerful execution out of practices that Porpora helped invent. Ornaments of fiendish length, tempo and range spur Fagioli onto ever-greater displays, racing ahead of the band. He is intense, yet precise.' (BBC Music Magazine).

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC

Also available on DVD.

Hasse: Artaserse (1730 Venice Version)

Anicio Zorzi Giustiniani (Artaserse), Maria Grazia Schiavo (Mandane), Sonia Prina (Artabano), Franco Fagioli (Arbace), Rosa Bove (Semira), Antonio Giovannini (Megabise)

'[Fagioli] is a magnificent artist, whether spinning out a gorgeous melodic line in “Se al labbro” in Act 1, with real legato and beautiful trills, or attacking the almost terrifying “Parto qual Pastorello”, with its 20-second, messa di voce opening note, [and] thousands of up and down cascades.

Available Formats: 3 CDs, MP3, FLAC