Further Reading

1st May 2015

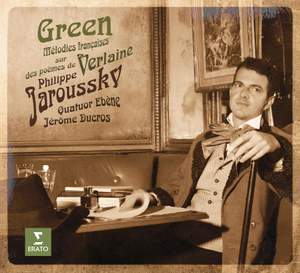

Katherine talks to the countertenor about his latest disc exploring settings of the great French symbolist poet.

In his second album of French song from the 19th and 20th centuries – following the ground-breaking Opium, released in 2009 – countertenor Philippe Jaroussky explores settings of poems by Paul Verlaine (1844-96). One of France’s most revered fin-de-siècle poets and a pioneer of the decadent and symbolist movements, Verlaine famously declared his philosophy in the first line of Art poétique in 1874: ‘De la musique avant toute chose’ – ‘music before all else.’ In his poetry, the sound and the shape of each line carries meaning and expression, adding resonance to the words, which often evoke a twilit world of ambiguous emotions.

Verlaine has duly inspired many French composers – from his contemporaries, such as Debussy (whose piano piece Clair de lune draws on the poem of the same name and features on this album), Fauré, Saint-Saëns, Massenet and Chabrier, through the following generation (Honegger and Varèse) to songwriters from the 1940s-1970s, including Georges Brassens, Charles Trenet and Léo Ferré.

The album takes its title from one of the poems in the collection Romances sans paroles (‘Songs without words’ – the musical connection again). Verlaine himself gave it an English name, ‘Green’, and there are no fewer than three settings in Jaroussky’s recital – by Debussy, Fauré and André Caplet, the latter best known for his orchestrations of Debussy piano music.

Jaroussky, speaking of a Verlaine setting by Reynaldo Hahn, has said that poet and composer “conveys a feeling of both moonlit abstraction and of the allusive, but very sensual caress of the beloved. There is always a sensual element in Verlaine’s writing.”

That languorous yet understated sensuality belongs to a different world from the Baroque repertoire most closely associated with Jaroussky. When he recorded Opium with pianist Jérôme Ducros (who returns for the follow-up), he said: “Many people will probably wonder why a countertenor should sing these songs, but if you think about it, the countertenor voice as such has no repertoire of its own, except the modern music written specifically for it. For the most part we sing music written for castratos who – as we know – had very different voices from ours. So why not venture into other musical worlds if we feel they are suited to our voices?

“I’ve always felt a special affinity for French song,” he continues. “Even if a singer has to master a number of languages, his own language always retains a special flavour – especially French, which has so many vowels and secret nuances ... In Debussy, Massenet or Reynaldo Hahn, it’s all a matter of shades of colour.” It is this sensitive, insightful approach that Jaroussky brings to Green.

If the essence of this kind of French song can be elusive, Forum Opéra praised Jaroussky for capturing it in Opium: “His attention to diction, bringing it close to spoken language, draws out all the meaning of the poems. Thanks to his musical intelligence and long-breathed phrasing, each of these songs is spun out to the fullest effect ... They haunt the memory ...”

For Green, Philippe Jaroussky and Jérôme Ducros are joined by some distinguished guest artists: the contralto Nathalie Stutzmann (on whose Handel album Heroes from the Shadows, Jaroussky sang in duet), and the Ebène Quartet, whose award-winning recordings of French chamber music form a pillar of the Erato catalogue.