Interview,

Simon Callaghan on Reinecke

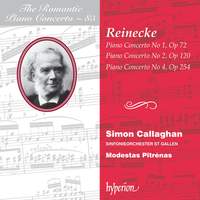

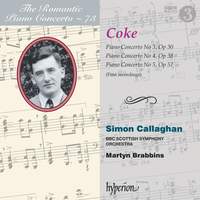

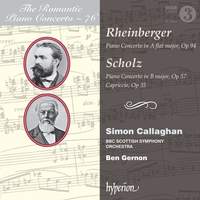

Given his passion for championing repertoire that's fallen by the wayside, it's no surprise that the British pianist and academic Simon Callaghan is becoming something of a stalwart of Hyperion's Romantic Piano Concerto series - after flying the flag for Josef Rheinberger, Bernhard Scholz and Roger Sacheverell Coke, his latest contribution to the project (released in January) features three works by the German composer Carl Reinecke (1824-1910).

Given his passion for championing repertoire that's fallen by the wayside, it's no surprise that the British pianist and academic Simon Callaghan is becoming something of a stalwart of Hyperion's Romantic Piano Concerto series - after flying the flag for Josef Rheinberger, Bernhard Scholz and Roger Sacheverell Coke, his latest contribution to the project (released in January) features three works by the German composer Carl Reinecke (1824-1910).

Having been inspired by Simon's enthusiastic advocacy for the music of Coke when we spoke during the final stages of his doctoral thesis on the composer's life and work in 2017, it was a pleasure to catch up again last month to discuss all things Reinecke - including his friendship with Mendelssohn, his roster of illustrious students, the piano-roll recordings of Mozart which he made in his 80s, and whether or not composers 'have an obligation to be forward-looking and innovative'...

Photo by Kaupo Kikkas.

How familiar were you with Reinecke’s music before you started working on this recording?

It’s fair to say that I was rather less academically well-prepared for this project than I was for the Roger Sacheverell Coke recording, which was born out of my doctoral research on the composer: Reinecke was suggested to me by the Hyperion team, and of course I was delighted to have the opportunity to make another recording as part of such a prestigious series!

The Flute Sonata Undine was the one work of Reinecke’s which I’d played a lot – around ten years ago I had a residency at the Banff Centre in Canada and was playing for a couple of their classes, including the class of legendary American flautist, Tara Helen O’Connor. Almost everyone was playing Undine and I was just delighted, partly because it has a really good piano-part and partly because I didn’t realise that the flute repertoire had this Romantic work: I knew the French and contemporary and baroque stuff, then there’s a gap in which this piece sits really confidently on its own. And I thought ‘I’ve done exactly what I criticise other people for doing: knowing one piece by a composer and really liking it, but not making any effort to look into any of the others!’.

Reinecke had an exceptionally long composing career, with forty years separating the first and fourth concertos on the album - how much did his orchestration and harmonic language evolve over that time-period?

What I find interesting is how consistent his style remains across those four decades – it’s perhaps a little extreme to say that he shifted back, but the fourth concerto feels to me like it would fit the title No. 1 better than No. 1 itself does! I was revisiting Jeremy Nicholas’s liner-notes yesterday and I came across one statement which made me cackle a bit when we were putting the recording together: ‘That the second concerto falls below the exalted standard of the first is inescapable’.

Jeremy and I had a spirited and rather funny email exchange about that at the time, because I’m always quite uncomfortable when people assert opinions like that as if they’re objective fact: I don’t mean to criticise Jeremy, but I think the two concertos are simply very different in lots of ways. The finale of No. 2 is really inventive and quite virtuosic, but also just a lot of fun! And the work does have memorable melodies – the Adagio is really gorgeous, probably my favourite movement, in fact!

Do you think that Reinecke’s tendency to stay within his musical comfort-zone has contributed to the neglect of his music since his death?

Very possibly. I remember having a similar conversation in the viva for my PhD when one of the examiners described Coke’s music as being derivative, but then questioned whether ‘derivative’ is necessarily a derogatory word…Why can’t people compose around things that have already been written and sit comfortably within an older style of writing?

It’s too simplistic to just dismiss No. 2 as a lightweight, old-fashioned kind of piece. Jeremy’s wonderful notes led me to look into what else was going on musically at the time, and I came across this really cool feature on Wikipedia where you can enter a year and find out everything that happened – premieres, births and deaths, all kinds of things. I discovered that Reinecke’s Piano Concerto No. 2 was premiered in the same year that Tosca was premiered, and Dream of Gerontius was written!

Putting it in context like that really got me thinking: was Reinecke behind the times, or was he just really happy in what he was doing? And if he was behind the times, is that such an obstacle to us enjoying his music today? Do composers have an obligation to be forward-looking and innovative, or is that something we’ve imposed on them retrospectively?

The booklet-note suggests that he was quite sanguine about the shelf-life of his music: ‘I will not indulge in the misleading hope that my works are set to endure for very long’...

Yes, except for the pieces that he wrote for young people! I was thinking just this morning about Reinecke’s purpose in composing, and how the reception of his music is now coloured by this assumption that one should write music to last forever or to surpass anything that’s gone before – whereas I sense that some of these concertos (and certainly the First) were probably just written to entertain and as a platform for him to show off his skills as a performer, rather like Mozart’s concertos. We don’t have anything from Reinecke explicitly confirming that in writing, but it’s certainly the impression I get. Again it’s easy to assume that just because the second concerto doesn’t make Jeremy Nicholas remember the melodies quite so well that there’s something wrong with it - but maybe Reinecke wasn’t that bothered about whether people remember the melodies or not!

Speaking of Mozart, Reinecke recorded some of his music on piano-roll when he was in his 80s - were you able to get your hands on those recordings, and what do they tell us about his style of playing?

There’s a fascinating website which I came across when I was preparing for the recording, which brings them all together. I’m always slightly dubious about piano-rolls, in terms of how well they’ve been recorded and whether they really reflect what was going on – but yesterday I listened to the slow movement of Reinecke playing Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23 (K488) and it occurred to me that if I was to play that recording to the people who taught me historically-informed harpsichord and fortepiano at college they would spontaneously combust!

It’s so far away from what they would say is the way that it 'should' be played – every chord is spread, the left hand and right are never together, the ornamentation is not what we know as ‘classically-informed’ ornamentation. It’s so cheesy in places, but it just made me think. Reinecke was born in 1824, just thirty years after Mozart’s death: he’s so close to that tradition, so who is to tell us that Mozart didn’t want it to be played like that?

His recording of K488 is without orchestra, so he plays the tuttis as well, and it just sounds like somebody improvising their idea of the piece in a bar after a few pints! I love that, because it has this genuine freshness: you get the impression that he just really likes the piece and is having fun in communicating that without being stuck up or held back by any inhibitions.

Given that Reinecke was so renowned as a Mozart interpreter, do you see any homage to the composer in his own music?

I don’t think so. Every biography of Reinecke talks about him being a great Mozart-player, but frankly if I hadn’t heard anybody say that then I don’t think I’d have come up with the connection solely through listening to these pieces. The concertos are all very Classically-influenced, and technically they’re kind of showy: there’s lots of right-hand filigree like you get in Mozart, but that isn’t something that’s unique to Mozart. I think it’s more a case of Mozart’s influence filtered through a number of other people over the decades, really: I guess we don’t talk so much about Mendelssohn being inspired by Mozart, but that’s something that’s been on my mind as I prepared for this conversation…

I think Mozart comes through more in his own style of playing rather than in his compositions, certainly if these concertos are anything to go by. But having said that, Reinecke wrote 280 opus numbers and I probably know six or seven, so I’d be very happy for someone who knows more of them to disagree with me!

Speaking of Mendelssohn, how strong an influence was he on Reinecke’s career and style?

I think their relationship was quite a close one; Reinecke’s debut as a concert-pianist was conducted by Mendelssohn, so they’d met a few years prior to that, and because they were both based in Leipzig they seem to have been in touch fairly regularly. And I’m fairly sure that Mendelssohn must’ve had something to do with Reinecke’s appointment as Director of Concerts at the Gewandhaus in 1860, given that he was such a mover-and-shaker in the city.

It reminds a little of the dynamic with William Sterndale Bennett, another composer who was very close to Mendelssohn and is often sidelined today as being similar in style but not quite as good! But I’ve a feeling that both Reinecke and Bennett actually influenced Mendelssohn quite a lot, because Reinecke became such a prominent figure…I wonder if part of the reason why he hasn’t stood the test of time as a composer was because he was invested in so many other things - whereas Mendelssohn was able to focus most of his energy on composition, Reinecke seems to have exerted his influenced in lots of different areas. He spent thirty-five years at the Gewandhaus, which was an enormous role in itself, and his list of students is enormous - he taught pretty much everybody who was anybody, including Grieg, Sullivan, Bruch, Albéniz and Janáček!

Do you have plans for further explorations of his music?

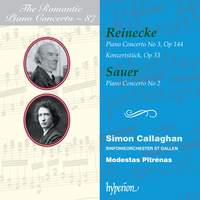

There’s also the Piano Concerto No. 3 and the Konzertstück, which we'll be recording in May. Reinecke also wrote one of the few Romantic piano sonatas for left hand alone; that would be really interesting to look at, and given that I run a chamber music series I should also investigate some of his works for piano and strings…

Simon Callaghan (piano), Sinfonieorchester St Gallen , Modestas Pitrėnas

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Simon Callaghan (piano), BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Martyn Brabbins

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Simon Callaghan (piano), BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Ben Gernon

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Simon Callaghan (piano), Sinfonieorchester St. Gallen, Modestas Pitrėnas

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC