Interview,

Florian Sempey on Rossini

Rossini's wheeler-dealing Barber of Seville has become something of a signature-role for the French baritone Florian Sempey, who's flourished Figaro's razor at opera-houses including Covent Garden, the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma, the Opéra de Paris and the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro over the past decade. It's fitting, then, that his first solo recording (an all-Rossini affair, released on Alpha Classics at the end of April) opens with the hairdresser-cum-fixer's ebullient 'Largo al factotum' - but as I discovered when we spoke via Zoom last month, he's come to believe that Figaro's apparent joie de vivre is underscored by a melancholy not unlike that which haunted the composer himself...

Rossini's wheeler-dealing Barber of Seville has become something of a signature-role for the French baritone Florian Sempey, who's flourished Figaro's razor at opera-houses including Covent Garden, the Teatro dell'Opera di Roma, the Opéra de Paris and the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro over the past decade. It's fitting, then, that his first solo recording (an all-Rossini affair, released on Alpha Classics at the end of April) opens with the hairdresser-cum-fixer's ebullient 'Largo al factotum' - but as I discovered when we spoke via Zoom last month, he's come to believe that Figaro's apparent joie de vivre is underscored by a melancholy not unlike that which haunted the composer himself...

What’s your first memory of hearing Rossini’s music, and when did you realise it would play a central role in your career?

My very first encounter with Rossini was at my grandpa’s house when I was a little child: they had a bust of him on their piano, and I remember asking ‘Who‘s that guy over there?!’ and being told ‘Oh don’t mind him, he’s just Rossini!’. I still didn’t really have any idea of who he was, but I figured he must be pretty special for them to have a statue of him sitting in their drawing-room!

I started my musical studies as a pianist, but when I switched to singing I realised that ‘that guy over there’ was an extremely famous opera-composer! I think the first piece of his that I heard was the Sinfonia for L'Italiana in Algeri, which is still my favourite Rossini to this day. And the first time heard Il barbiere di Siviglia I just fell in love with the character of Figaro and the music: it’s so sparkling, powerful and joyful.

Which singers - past or present - do you find especially inspiring in this repertoire?

That first Barbiere I heard and saw was the Schwetzingen Festival production, with a very young Cecilia Bartoli in her debut as Rosina and Gino Quilico as Figaro. Then of course I heard Maria Callas’s recording of Il Turco in Italia: it’s such a pity that she didn’t record more Rossini, but what we do have is wonderful! A little later I discovered one of my favourite singers of all time, especially in this repertoire: Marilyn Horne. I was very lucky to work with Alberto Zedda shortly before he passed away, and he told me that if you want to know how to sing Rossini just listen to Marilyn. It was sound advice! I like pretty much any big Rossini singer you care to name – but it was through listening to Horne and Bartoli that I really came to understand Rossini and bel canto style.

And which stage-directors have really influenced your thinking on Figaro’s character?

For me there is Barbiere di Siviglia and Figaro BEFORE Laurent Pelly and there is Barbiere di Siviglia and Figaro AFTER Laurent Pelly! When I did his new production at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysée in 2018, he came up to me on the first day of rehearsals and said ‘Look, I’ve seen you in Barbiere and you were great and everything…but I want to let you know that I think that Figaro is actually not all that joyful, and not all that kind to others’. And I agree, because when you read the Beaumarchais play and the libretto it becomes clear that Figaro is really motivated by greed: sure, he agrees to help people meet and to keep their secrets, but the first thing he wants is money. It was very interesting to work on that with Laurent, and then my Figaro became something…not exactly dark, but a bit jaded and fed-up. There are too many people coming to him wanting things, and that life isn’t something he’s enjoying any more.

Only last week I messaged Laurent from Toulouse where I’m doing Barbiere now: I sent a picture of my face as Figaro saying ‘You know where I am, and what kind of production I’m doing - even with a very different production, your Figaro is always very close to me’. Of course I have to adapt my acting to what the director wants - I can’t just do my own thing! - but I always keep Laurent’s ideas in my mind. Even if it’s only through the eyes, I like to express that this is a man who’s desperate for cash and just wants to be left alone. In the next part of the story, Le nozze di Figaro, you see Figaro becoming more political and really clashing with the Count, but for me you already have the seeds of that French Revolutionary spirit right there in Barbiere.

You’re currently singing Count Almaviva in Le nozze di Figaro - does the experience of playing Figaro himself feed into the way you approach that character?

I don’t really dwell on that too much, to be honest: it’s the same story and same characters, so it’s just a case of taking off my Figaro hat and putting on my Count hat! I’ve had to switch between the two very quickly this month, but I’m lucky enough to have done this production of Le nozze di Figaro quite a lot since 2015 so I’m used to the role and the staging. One thing I do have to remember is to move my hands less as the Count: Figaro makes a lot of big gestures and the Count is much stiller, so I tend to put my hands behind my back to avoid the temptation!

L’Italiana in Algeri is quite a problematic piece to stage these days in terms of the way it depicts the clash between two different cultures - but as you said earlier the music's glorious! Do you think the right director can still make it work?

I hadn’t actually considered that with respect to L’Italiana, but I asked myself the same question when I was doing Così fan tutte recently: when you look at the libretto in the wake of the #MeToo movement, you can’t help but think ‘how can we still play this piece today?’. But at the end of the day I’ll always be the defender of the theatre against criticism, because the thing is that it’s only theatre - sure, it’s for making people think a little about society sometimes, but first of all it’s three hours of joy and forgetting your problems. That’s what the theatre and we artists are there to provide.

The excerpts from the big three comic operas here will probably be quite familiar to most listeners, but the arias from La scala di seta and L'occasione fa il ladro perhaps less so...what's special about these pieces for you?

I chose them because they’re never done, and because they’re very difficult to sing – you can find them each year in one or two theatres maybe across the world, but you need very good singers and musicians to achieve that, more so even than for the 'big three'. And I also wanted to acknowledge that Rossini isn’t only about that joy that we all love him for: he suffered from what they called melancholy in those days, but today we would probably call it burn-out. Perhaps it was triggered by the death of his mother, perhaps he simply became depressed, but we know that after Guillaume Tell he stopped composing - after that he wrote nothing apart from the Petite Messe solennelle and the Péchés de Vieillesse.

We hear that melancholy in Guillaume Tell, of course, but it’s also there in parts of La scala di seta: those big long sustained lines in ‘Amore dolcemente’ could be by Bellini or Donizetti, and that’s a part of Rossini’s style too. I wanted to show that Rossini is not only buffo (like we see in Barbiere and L’Italiana), it’s bel canto too. Teresa Berganza used to say ‘Rossini’s my master’, and I feel the same way, because if you can sing Rossini more or less correctly then you can sing pretty much everything else - it helps you understand how to manage your breath and place your sound to make it beautiful.

Tell me a little about your relationship with your two guests on this recording…

They’re both very good friends. I’ve known Karine for ten years now, and she’s sung Rossini everywhere in the world, including at the Metropolitan Opera, so when I needed a Rosina and Isabella I called and said ‘Please tell me you’re available!’. (She wasn’t, but she managed her schedule to free it up!). I was very happy she could join me for this project, and I couldn’t imagine anybody better: our vocal colours mix perfectly, and so do our personalities. We both love life and champagne, and Rossini’s all about that - not just the pleasure of singing but all the pleasures of life!

Nahuel is a lot of fun to work with, too: we’ve done Le Comte Ory together and some concerts and a gorgeous production of French baroque repertoire, and we get on so well. He has a beautiful bass voice that’s just ideal for big Rossini and serious repertoire, so he was another perfect choice for me.

Speaking of big Rossini and serious repertoire, might Guillaume Tell figure in your future?

I’m still too young for Guillaume Tell, but it’s a very beautiful role and I hope to be able to sing it in maybe ten years. I’m already singing French repertoire like Valentin in Faust and Zurga in Les pêcheurs de perles, but I think casting-directors still see me as Figaro. To be honest I’m fine with that, because I love the role and the opera: it’s not like coloratura sopranos who sing so many Queens of the Night that they grow to hate it! But sometimes it’s good to remind people that I do sing some serious repertoire too - even if I’m not a very serious person in real life…

Florian Sempey (baritone), with Karine Deshayes (mezzo), Nahuel Di Pierro (bass)

Orchestre National Bordeaux Aquitaine, Marc Minkowski

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

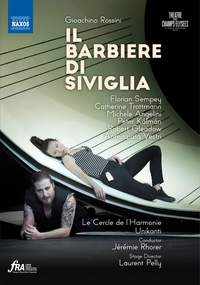

Florian Sempey (Figaro), Catherine Trottmann (Rosina), Michele Angelini (Almaviva), Péter Kálmán (Bartolo), Robert Gleadow (Basilio), Annuziata Vestri (Berta)

Le Cercle de l'Harmonie, Jérémie Rhorer, Laurent Pelly

Available Format: DVD Video