Interview,

Bojan Čičić on Adriatic Voyage

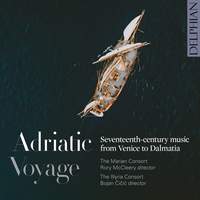

The idea of assembling a programme exploring cross-cultural connections between Venice and his own homeland in the seventeenth century had been on Croatian violinist Bojan Čičić's radar for almost a decade by the time he and his Illyria Consort joined forces with the Marian Consort and cornettist Gawain Glenton to record Adriatic Voyage; the ear-opening results proved a palpable hit with the Presto team, with the album featuring in our Top Ten Recordings of 2021.

The idea of assembling a programme exploring cross-cultural connections between Venice and his own homeland in the seventeenth century had been on Croatian violinist Bojan Čičić's radar for almost a decade by the time he and his Illyria Consort joined forces with the Marian Consort and cornettist Gawain Glenton to record Adriatic Voyage; the ear-opening results proved a palpable hit with the Presto team, with the album featuring in our Top Ten Recordings of 2021.

In a break from rehearsals for a Wigmore Hall concert shortly before Christmas, Bojan spoke to me via video-call about the lives and works of the composers featured on the album, how a seventeenth-century travel-diary provided the focal point for the project, and how he and his colleagues set about tracking down the repertoire for the recording and bringing it to life...

Could you give me a potted history of the composers featured on the album and their relationships with Croatia and Italy?

In order of appearance…Francesco and Gabriele Usper were born in Rovinj (or Rovigno), a town in Istria. With the exception of Vinko Jelić, all of these composers came from cities which were part of the Venetian Republic, and the two Uspers were closest to Venice in terms of geographical proximity to the city itself; Francesco was an organist in Venice, and there are a fair amount of opuses that were published there during his lifetime. The other Usper, Gabriele, was his nephew – in one of the collections from 1619, the vocal pieces were written by Francesco and some of the instrumental works were written by Gabriele. (Usper’s original surname was Sponga, but he took the name of his benefactor; sometimes in Croatia we put his birth-name in the programme instead, but here he’s known as Usper because of his Sonata à Otto, which is basically the one piece by him that’s often performed).

Then we move onto Gabriello Puliti, who was an Italian working in Istria. Puliti was one of the founding members of the Florentine Camerata, along with Giulio Caccini; this represented the very beginnings of baroque music, with monody being turned into song using continuo instruments and incorporating motives and themes from antiquity, and Puliti was among the composers who were trying to set up a camerata around other parts of the Venetian Republic so he travelled around present-day Istria and went back and forth to Italy.

Puliti was known to have composed a lot of parodies, including the third piece on the album: En dilectus meus, which is a parody of Palestrina’s Vestiva i colli. There’s an opening section of a few bars, then the soprano part has exactly the same line as the Palestrina; Gawain’s idea was to replace the soprano part with his diminutions by Giovanni Bassano. We started rehearsals with everybody playing and the idea was for the instruments to double the voices and see what came up, but Gawain said ‘How about we get rid of the sopranos, and I’ll be the soprano with the other four voice-parts underneath? That way we’ll have a kind of perfect polyphony with an ornamented top line’. That was a genius stroke for getting the fire from that piece.

Next we meet Vinzenz Jelich, or Vinko Jelić – he was born in Rijeka (‘Fiume’ in Italian), which is our biggest port in in Croatia. It’s a really interesting city, because like Trieste (which is only about sixty kilometres away) it was a gateway to the Habsburg empire. Jelić then went to Graz with Leopold V and ended up following him to Strasbourg, where a lot of his music was published, including these vocal pieces and this instrumental ricercare from around 1619.

Of the two remaining Croatians, one of them is very much a Renaissance composer: Giulio Schiavetto or Julije Skjavetić, who wrote this Ave Maria (which the Marian Consort sing a cappella) in the mid-sixteenth century. He’s followed by an Italian composer, Bartolomeo Sorte, who doesn’t have anything to do with Croatian lands but is very important because of the theme of Giacomo Soranzo who was the nobleman who travelled on that ‘Adriatic Voyage’ from Venice to Constantinople in 1573. One of his entourage kept a journal, just a simple diary of how far they sailed each day and where they disembarked: we know they landed in Poreć, in Šibenik (where Skjavetić came from), and in Split where Tomaso Cecchino came from a little later on. We took that as a base to follow their journey around the coastline, and that’s why Sorte’s madrigalI superbi colossi is on the programme, because it actually mentions Soranzo - three decades after he made the voyage!

The other Šibenik composer is Ivan Lukačić, a Jesuit priest who trained in Split and then in Rome. He eventually came back to Šibenik, and the works that we recorded were published in Venice whilst he was living in Šibenik.

Then we go to Tomaso Cecchino (known as ‘Il Veronese’), a composer from Verona who did things the other way round: he came from central Italy to Croatian lands and initially settled in Split. He was the organist at Split Cathedral and was friends with the archbishop Marcantonio De Dominis, who became persona non grata in the church: he was basically excommunicated by the pope for his Protestant sympathies, and Cecchino stood by him. We don’t have any details of Cecchino's life for a few years after he left Split, but later on he ended up in Hvar, one of the islands in Southern Dalmatia, where he was a kapellmeister and composed some of this music. The musicians and singers there weren’t as virtuosic as the ones they’d have had in Venice, so the music is fairly simple - but we tried to enhance it by adding diminutions and in some cases enriching the orchestration. In his Sonata No. 8 we had two sets of not just soloists (cornetto and violin), but also two sets of continuo instruments: the organ only played with me and the theorbo with Gawain, so we tried to make it as complicated as we could!

For the final track we went back to Venice and Francesco Usper with the biggest piece on the album, his Battaglia à otto for eight voices and eight instrumentalists. (We actually had five voices rather than eight, but we did have eight instrumentalists). The only other recording is by Jordi Savall, on his 1985 album Battaglie e Lamenti, but he only uses two singers. The orchestration he does is interesting: one coro is cornetts and sackbuts and the other is just viols. But that’s not actually what Usper wants: he asks for sackbuts on the alto line in both orchestras. We tried to do that, but still kept one side of the stage winds-only – their side was two cornetti and dulcian, and then my side was violin, sackbuts, viola and bass violin.

How pronounced are the stylistic differences between the Italian and Croatian composers? Is it always obvious which is which?

Maybe not so much with Usper, because he very much belongs to the soundworld of Gabrieli – if anything, the music corresponds to the Venetian music from maybe twenty years earlier in style. Perhaps you could say that Lukačić was pushing the envelope a bit by using a lot of solo voice and continuo passages in his choral works, but I wouldn’t say it was at the forefront of progressive music. Certainly it had nothing do to with the music by Castello and Monteverdi that was being published and performed in Venice at the time - and that makes sense, because these were the provinces whereas Venice was the epicentre of music publishing and travel.

I recently read a review of the album by somebody in New Zealand who complained that so much of the music on the album was church music, but the reality was that most of the educated people in Croatia at the time were priests or something to do with the church. The majority of the population didn’t have knowledge of Latin or other languages, let alone music; they could sing, probably, but composing and publishing music wasn’t happening in the provinces.

So essentially everything was a few decades behind what was going on in Venice. I’ve done some projects with Bolivian Baroque, and again a lot of that music sounds like it was written thirty or forty years before the year it was published. These guys weren’t out there hearing Hasse operas; they were just Jesuit priests who went to these places and had to set things up from scratch, and in that situation it makes sense to bring something that you know well and can perform.

What (or who) were your main sources for the music itself and for the biographical information on the composers?

The Croatian musicologist Ennio Stipčević wrote biographies of Usper and Lukačić, which were published by the Music Informative Centre Zagreb. Stipčević isn’t in the best of health, but I was briefly in touch with him when I was searching for the music of the Usper Battaglia and he was very excited about what we were doing.

I also had lots of input from Bojan Bujić, who was a lecturer at Magdalen College Oxford before his retirement. Monteverdi and Schoenberg were his areas of expertise, but having been born in Bosnia and studied in Zagreb he was also interested in this particular era: he provided a lot of the music for the album, and he was the one who suggested that travel-diary as the focus. I think it was back in the spring of 2012 that we started working together, not on this particular programme but on the idea of juxtaposing Venetian and Croatian music. I did have a programme in mind back then, but the difference was that all the vocal pieces were Croatian and all the instrumental pieces were by Venetian composers (Kapsberger, Rossi etc) who had nothing to do with Croatia. Whereas for this album we did instrumental pieces by the composers whose vocal music we also performed, so it was a bit of a discovery.

Much of the music is published: some of it (including the Vinko Jelić) is kept in Basel, so I had Gawain Glenton copying music when he went there a long time ago. Some pieces had only recently been published, or existed only in manuscript on imslp – whatever Jordi Savall used for the Usper was the only thing that was available for a long time, but as the piece does get performed fairly often it must’ve been a case of people making their own parts. I believe that this programme will show not only the rich cultural heritage which Croatia has due to its proximity to the major centres of Europe in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, such as Venice, but also the quality of music composed at the time mixed with the quality of musicians in the early twenty-first century performing it, following Illyria Consort’s guiding light: it’s not about what you perform, but how you perform it.

Bojan Čičić (violin), Gawain Glenton (cornett), The Illyria Consort, Marian Consort, Rory McCleery,

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC