Interview,

Christian Immler on Hans Gál

It must have been around a decade ago that an Edinburgh-based pianist friend of mine alerted me to a set of five remarkable songs by the Austrian-born composer Hans Gál, who settled in the city after fleeing Vienna in the late 1930s; fascinated by their strange beauty, I was disappointed to find that no other lieder by Gál appeared to be available in print or on record, so it was a special pleasure last month to discover that the German bass-baritone Christian Immler and his regular recital-partner Helmut Deutsch had given twenty-six unpublished songs their world premiere recordings on BIS.

It must have been around a decade ago that an Edinburgh-based pianist friend of mine alerted me to a set of five remarkable songs by the Austrian-born composer Hans Gál, who settled in the city after fleeing Vienna in the late 1930s; fascinated by their strange beauty, I was disappointed to find that no other lieder by Gál appeared to be available in print or on record, so it was a special pleasure last month to discover that the German bass-baritone Christian Immler and his regular recital-partner Helmut Deutsch had given twenty-six unpublished songs their world premiere recordings on BIS.

I spoke to Christian over Zoom last week about why so many of these songs were 'laid aside', how he and Deutsch persuaded the composer's family to grant them a new lease of life, and their plans to explore the song output of other neglected Viennese composers from the same period.

How did Hans Gál come onto your radar?

Shortly after I finished the opera course at the Guildhall I did a lunchtime recital of contemporary music at the Crush Room at Covent Garden, and afterwards Michael Haas (the former Executive Director of Decca’s Entartete Musik series) came up and offered me a recital at Wigmore Hall: he’d been tipped off that I was interested in unusual repertoire, and thought they might have something for me. That in turn led to a CD called Continental Britons (with pianist and musicologist Erik Levi) which featured music by Egon Wellesz, Berthold Goldschmidt, Karl Rankl and also Hans Gál: I was aware of Gál’s books on Schubert, Wagner and Brahms but until then I hadn’t come across his music, and it was an amazing discovery.

On the back of the CD release I was asked to do a recital at Kings Place in London, and I asked Helmut Deutsch to join me for that: it turned out he has a strong interest in this post-Romantic repertoire, especially songs which haven’t been recorded or performed. I think you really have to have this idiom in your fingers, as it requires quite a specific approach: it’s all about how you link phrases without excessive rubato, but it can’t be too dry either. Helmut is the master of 'gliding' between the keys and using their full length and depth. Our first recording project together was a disc of Korngold, Zemlinsky, Schreker and Goldmark, and we’ve been pooling our resources ever since: we’re both passionate about this repertoire, and I couldn’t wish for any better partner!

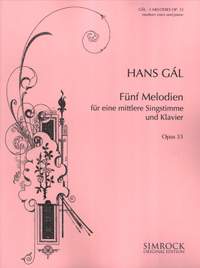

We closed the Kings Place concert with Gál’s Op. 33 songs; his daughter Eva Fox-Gál was in the audience and we got talking afterwards. Helmut and I were musing that there didn’t seem to be any other song output, and she said ‘Well actually there is, but it’s all officially laid aside and it’s all in manuscript…You’re welcome to come to our house in York and explore’. We took her up on the offer and had two wonderful days looking at the manuscripts: they were all really beautifully written, so we could read through things very easily.

How closely were the family involved in the recording-process?

At first Eva was resistant to pursuing a recording, because she was very conscious that her father had put these songs aside, and it took me literally years to talk her round. She’s committed to making sure that her father’s legacy is being seen in the right light, but now that many of Gál's big orchestral works have been recorded and the operas are being performed (and that’s what her father considered to be his main compositional output) the songs have more context. I think she never wanted to feel that she was overriding her father’s will, but Helmut’s and my stance was always ‘he could have burned them’: he destroyed hundreds of early songs (and even his first symphony, which after all had won the Vienna State Prize for composition in 1915) which didn’t meet his high standards, but these were simply put aside in a box and labelled 'requiescant in pace'.

Eventually Helmut and I sent Eva a recording we’d made on a small MP3 player at his home in Vienna, because we wanted to show her that many of these songs were at least on a par with Op. 33, and once she heard it she said ‘This is actually fantastic – go ahead!’. Eva’s husband Dr Anthony Fox-Gál helped us tremendously by putting these manuscripts into Sibelius so we could transpose things down, which helped us create coherent connections from one song to the other.

Is there any evidence that Gál planned to return to any of these songs?

It‘s pretty certain that he never wanted to come back to them: I think he’d said as much as he wanted to say in the genre in Op. 33, and then he moved onto bigger forms like the symphony and opera. About a year before Gál passed away, he did an interview with Martin Anderson at Toccata Classics where he said his ‘conscience was clear’ with regard to his older works: he was extremely conscientious about quality-control, and very proud that he never published anything he later regretted. Personally I could never quite understand the resistance about the songs, because they’re so high-quality and atmospheric, but I’d hope that he would have been pleased with what we’ve done here.

Which composers do you see as his major influences in the genre?

Definitely Schubert, Schumann, Wolf (he transcribed a suite from Wolf’s opera Der Corregidor), and above all Brahms. I think there were some reviewers who accused Gál of being a copycat at times, but I think that’s the wrong approach: we can’t chide somebody for picking things up or wanting to emulate somebody like Brahms, and Gál had enormous respect for the mastery of these earlier composers. And he internalised all of their writing skills in a very practical way – he became an excellent teacher later on and was apparently greatly admired by his pupils because he could play so much from memory.

Gál's lineage as a musicologist is also interesting: his mentor, teacher and life-long friend Eusebius Mandyczewski brought out the entire Brahms edition and the first complete Schubert edition, and Gál worked alongside him on these projects. Mandyczewski had been friends with Brahms, so there’s a direct ‘genealogy’ there, and you can see that in the way he treats the piano part in his songs. Gál was himself a very accomplished pianist, and Helmut commented many times that there is nothing against the piano – it’s extremely idiomatic and has a real pianistic finesse. Likewise the vocal lines have a beautiful natural flow! And I think that’s something he absorbed from older composers, simply by looking through and copying out their music and internalising certain chordal progressions and the like.

He was also very into early polyphonic music like Palestrina, from his early days in Vienna; right after his arrival in Edinburgh in about 1940 he set up an a cappella group for Renaissance music, and that’s another influence that I hear in some of his songs, for example the Minnelied and Morgengebet with texts by Walther von der Vogelweide. The harmonic progressions and the approach to setting text is extremely reminiscent of some early music, but it’s all done in his own style and that’s what I find so fascinating.

How was Gál affected by the two World Wars?

He was a soldier in World War One, and spent some time stationed in Northern Italy. As far as I recall he was lucky enough not to have much front-line duty due to his poor eyesight, and during this period he had several bursts of energy where he wrote songs, a bit like Schumann did in the 'Liederjahr' 1840. These bursts were usually connected to discovering the work of a specific poet (Morgenstern, for instance, was very dear to him), and I think the songs he wrote during the War do have a darker quality to them. But he never went in for all-out brutal depictions of war in the way that composers like Karl Rankl did: I have some of Rankl’s music in my library including a cycle called War (albeit composed during the Second World War), which is very jagged and ironic and includes a lot of bitter criticism of the Church in particular. That doesn’t happen in Gál at all; the undercurrents are certainly darker, but he was attracted to evocative yet 'pure' poems which would endure the passing of time. He was very struck by how all of a sudden our world order can so easily fall apart – and as you so aptly commented about Novembertag, that aspect of his songs still speaks very directly to us today.

During World War Two Gál fled Vienna for the UK, and ended up being interned in a camp on the Isle of Man as a result of Churchill’s ‘Collar the lot!’ campaign to round up refugees from Austria and Germany. He wrote a ‘Lager-revue’ there, which was basically a musical parody of a lot of things despite or rather in spite of the situation; the text was written by Otto Erich Deutsch, who did all the Schubert D numbers, so the intellectual capacity in this Lager was unbelievable. The Op. 33 song Drei Prinzessinnen (which is very sensual but also touches on the theme of exile) was performed by a baritone who was interned alongside them, and that became one of his most beloved songs.

Were any of the ‘laid aside’ songs performed during Gál’s lifetime?

Yes, most of them – it’s hard to be certain about private performances, but we do know that there were a couple of gala events, the first being in 1917 in Dresden where all six Morgenstern songs were performed. And Op. 33 was performed in 1920 in Vienna, and in Elberfeld in 1923; as I mentioned, Gál particularly loved Drei Prinzessinnen from that set and at the time of writing he had a harpist girlfriend, so there’s a version for voice and harp as well the one for voice and piano (her name was Steffy Goldner and she later became the New York Philharmonic's first woman musician). Some of the songs were likely only performed once, but it’s about time they were published and got the recognition they deserve. My hope is that this music becomes a tiny bit more mainstream, just as Korngold and Zemlinsky did.

Are there plans to publish the songs?

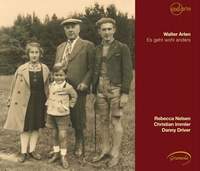

I put this to Eva and her answer is No for the moment, but she says she could imagine that if ever there was a Gesamtausgabe then that would be different. She’s very keen for anything that’s already published to be out there being performed and recorded, but I think there would be a significant amount of interest from younger singers in particular if the music was available: when Danny Driver and I recorded songs by Walter Arlen (a phenomenal composer who’s still going strong at 100!) a few years ago we were inundated with requests for the scores, and all I could do was direct people to the composer’s estate.

How many more songs did you discover, and how did you make your choices?

I can’t put an exact figure on it, but I think there are perhaps twenty or thirty more. At some point we had to make a selection, and of course we picked what spoke to us most profoundly - but for a CD you also need to think about variety of mood and pace. Sternenzwiesprach, for instance, is extremely lively and wordy, and it was great to have something like that to get the energy going during the recording-process!

We also took our cue from the Op. 33 set when we were thinking about the structure of the album. Although Op. 33 isn’t a ‘cycle’ in the sense of having internal quotations or any real narrative, it really has everything you need: nostalgia in Vergängliches, wonderment and suspense in Vöglein Schwermut (which I think is one of the most stunning songs ever, especially if the postlude is played so miraculously by Helmut), and that lighter yet more defined ballad style in Drei Prinzessinnen. The way Gál balances things is fantastic, and we tried to recreate similar small groups within the rest of the programme.

Do you have plans to record more?

This is the first in a planned mini-series which Helmut and I want to do for BIS – there’s a lot of repertoire to be unearthed in Vienna, and that will also be the focus of a doctorate I’m pursuing at the University of Montreal. Together with Professor Gerold Gruber, Michael Haas has co-founded a centre called exil.arte (the ‘Center for Banned Music’) in Vienna, and they have literally entire estates in boxes: last time Helmut and I visited, we realised that the challenge will be deciding what not to do, which is a great position to be in! For the next recording I’d like to go a tiny bit further back to a composer called Theodor Streicher [1874-1940], who was called the 'New Hugo Wolf' of his time, and it would be very interesting to see how he compares to Gál…Streicher’s music is more outwardly intense and dense – it’s really like Wolf on dope! Paul Pisk [1893-1990] is another very interesting composer, and I’m also keen to explore Karl Rankl. One does need to be pragmatic, though: great musicological finds don't necessarily make for a great recital disc. But I am confident we will find a good solution!

Christian Immler (baritone), Helmut Deutsch (piano)

Available Formats: SACD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Related recordings and publications

Nurit Pacht, Konstantin Lifschitz, Christian Immler, Erik Levi, Paul Silverthorne

Ensemble Modern Frankfurt

Available Formats: 2 CDs, MP3, FLAC

Christian Immler (baritone) & Helmut Deutsch (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC

Christian Immler (baritone), Rebecca Nelson (soprano), Danny Driver (piano)

Available Formats: 2 CDs, MP3, FLAC