Interview,

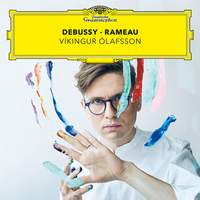

Víkingur Ólafsson on Debussy and Rameau

Ever since his 2017 debut album for Deutsche Grammophon of music by Philip Glass, Icelandic pianist Víkingur Ólafsson has made a name for himself as one of today's most intelligent and thoughtful performers. This Friday sees the release of perhaps his most accomplished album to date: a fascinating pairing of music by Debussy and Rameau. I recently spoke to Víkingur to ask him about the inspiration behind the album, and whether there are any characteristics that the two composers have in common.

Ever since his 2017 debut album for Deutsche Grammophon of music by Philip Glass, Icelandic pianist Víkingur Ólafsson has made a name for himself as one of today's most intelligent and thoughtful performers. This Friday sees the release of perhaps his most accomplished album to date: a fascinating pairing of music by Debussy and Rameau. I recently spoke to Víkingur to ask him about the inspiration behind the album, and whether there are any characteristics that the two composers have in common.

How did you first hit upon the idea of pairing these two composers, and what do you feel they have in common?

In March 2019, I found myself at home waiting for the birth of my son. I was supposed to be in Paris but then my son decided to wait two extra weeks before entering the world, so what I did was to get the complete keyboard works of Rameau in order to get to know this music. It was one of the most interesting days of my life, because I found incredible pieces of such quality that I could hardly believe. As I was exploring all these pieces, my mind kept turning to Debussy, and to the many parallels I found somehow with Rameau’s music. So that’s where the seed for this album came, and then I started to do some research and found out that Debussy was absolutely in love with Rameau. I knew the Hommage à Rameau from Images, so it was not a complete surprise to me, but the level of the connection was still a surprise. He was working as a music critic into his forties, and there is a beautiful review he wrote in 1903 of a performance of Castor et Pollux where he writes that Rameau seems to be our contemporary. That line stuck with me and that’s when I started to think about an album that would be like a conversation between the two composers, despite almost two hundred years separating their births.

I’m not trying to prove that Rameau was an Impressionist or that Debussy was Baroque, but there is a strong musical identity between the two in that they were relentlessly individual when it came to finding their own ways with music, and I would say that they’re also outsiders who came onto a scene that they found to be quite tired: Rameau came relatively late in the French Baroque, and Debussy arrived on a scene filled with things that he thought were uninteresting. We might not agree with him but he found that Saint-Saëns, Fauré and the French school of the day was lacking in invention, so he said “I will change the whole thing”, and I find this intellectual drive they both had to be very appealing.

What the two also have in common is an intensely poetic and theatrical nature. First of all you have these titles (Le rappel des oiseaux, L’Entretien des Muses, La poule, etc), and you have similar but more extreme things from Debussy like La Cathédrale engloutie, Jardins sous la pluie, those kind of incredible one-line poems. They’re painting these hues in sound, so the more I played the more I found a brotherhood between the two. It seems to me that Debussy’s roots are deep in the French Baroque, and that Rameau as a harmonist is so out of his time - he does things that could almost be written by Mahler. My transcription of The Arts and the Hours from his last opera (Les Boréades) is filled with suspensions and elevenths in the harmony that really belong to the late nineteenth century, not the middle of the eighteenth. So it’s about Rameau’s futuristic vision and Debussy’s receptive quality.

How helpful do you find those descriptive titles? I'm thinking especially of pieces such as "La Rameau" from the 1741 Pièces de clavecin: is it worth spending time working out whom that might refer to?

There’s probably never going to be an answer unless we find some documents somewhere. That doesn’t change the fact that it’s an immensely interesting enigma, just like all music is. I think it could refer to himself, his wife, or his household, but the fact remains that regardless of whom it refers to, it doesn’t take itself seriously - it’s the happiest, jolliest, most non-self-congratulatory portrait you can imagine. It’s not trying to paint a perfect picture of domestic life like Wagner’s Siegfried-Idyll or Strauss’s Symphonia Domestica: it’s saying ‘We are here to have a good time, we are the Rameaus’. These things are cryptic, but that doesn’t change the fact that to go into those questions adds a new dimension to the possibilities you have when you interpret it. I find that in a lot of French repertoire, their way of tackling existence is through the joy of the everyday, and I love that very much.

You have previously recorded an album of a contemporary of Rameau's, J S Bach: are there similarities that you found between the composers?

I think there are similarities but maybe they are coincidental. One of my favourite pieces on this album is L'enharmonique (from the Nouvelles suites), which is one of the most chromatic pieces Rameau ever wrote, and highly connected to his theories of harmony: if you compare it with the big slow variation of the Goldbergs, one of the great, intensely chromatic Bach laments, there are harmonic progressions there that you find strikingly similar - but whether that has to do with one composer bowing his head to the other, or simply the time they found themselves living in, that’s hard to say. It’s a bit like when I play contemporary composers: I’ve just done John Adams’s new piano concerto, and I’m now doing Thomas Adès’s older concerto. There are similarities there but I don’t think for a second that one was looking at the other while that happened: it’s something to do with the soundscape of our time.

There are many more differences, though. Rameau is more direct: he’s giving us a narrative and whether you like it or not you have to travel with him. Bach on the other hand gives you a more open alphabet and you can navigate your own way to a completely different point. It’s more enigmatic, and Bach is telling more than one story at a time. Bach is more intensely polyphonic, whereas Rameau tends to be more Schubertian: you have a lead actor and then the supporting scenery. I feel very much when I’m doing Rameau that I’m in the theatre: to me the E minor suite is like a scene from an eighteenth-century French village, whereas I would not say anything so specific about the suites of Bach.

Regarding the chromaticism of L'enharmonique; did it come as a surprise to you that the author of such a celebrated treatise on harmony ends up playing fast and loose with the rules?

Rules are there to break, I think, especially in art. Moving from Rameau to Debussy, the latter takes all the rules and throws them out the window, but he does so lovingly. It’s a bit like if you want to commit a bank robbery: you have to know every corner of the bank from the inside, and preferably to have worked there! A similar thing happens in performance: if you’ve really worked on a piece, meaning you take it much further than just being able to play it note-perfect, and you spend more time on it than you imagine you needed to, you can go on stage in front of a full house and completely change everything on the spot. Maybe you give the performance of your life not following any of the rules that you have so carefully decided for yourself. I believe very strongly in this, and I think that every time Bach wrote parallel fifths and octaves, he did so on purpose, to find the extra spice that it allows. They’re never a mistake, and if you remove them then the music suffers; they’re always there for the better, and the more “correct” way of doing it is worse. It’s the same with technique: you have to study your hand position in order to be able to completely forget about it on the spur of the moment in the concert hall. For me, art is all about this intense relationship between freedom and discipline, and that’s why I’m so drawn to the music of Rameau and Bach.

One of the things that struck me most about your album is how beautifully structured it is, darting back and forth between the two composers. Could you speak about how you decided upon the ordering of the album?

I tend to think of my albums almost like conversations, so it does take me a lot of time to decide which pieces to record. I had about ten different track orders in the course of making this album, and to make it work I tried to find bridges between the two composers. For the Prelude from the cantata La Damoiselle élue, I made a conscious decision not to use the ending from Debussy’s own transcription: he more or less reproduces the piece exactly, but at the end he pastes the final measures of the cantata. I’ve taken the liberty of not doing it like that, but simply going back to Debussy’s original ending. It’s as if we were in the theatre: you have the Prelude ending on this uncertain open E sonority, and then the curtains are drawn and you find this village scene from Rameau.

Just like the theatre, I thought of the album in two halves, with my transcription, The Arts and the Hours, as the beginning of the second half. Then the Hommage à Rameau is an afterthought, with a lot of silence before it appears, like a nostalgic reflection on the whole album. It’s been immensely interesting and my biggest challenge to date; I hope it’s more daring than other things I’ve done!

One of the things I did was to put Des pas sur la neige in the middle of the D minor Rameau suite, partly because it is similarly stuck around D minor, but it’s also very much the same sentiment as L'Entretien des muses, which precedes it. It’s like Rameau is telling Debussy everything that there is in the D minor suite, but Debussy chips into the conversation with his Footsteps before Rameau takes over with La Joyeuse. I thought of it like two guys having a conversation, just like you and me: one says something, the other one listens, and then takes that thread and spins it on.

You mentioned Debussy’s Hommage à Rameau which concludes the album. Clearly Debussy wasn’t attempting any actual pastiche, so what do you think it was about the essence of Rameau's music that he was trying to capture? Or is that too literal a way to think about it, and it's a much more intangible connection?

I think this is arguably the greatest homage in the history of music, and I don’t say that lightly. The beauty of it is exactly what you said: it’s an enigma, vaguely in the Sarabande form but not really, and it certainly does not sound like Rameau. This is one artist taking a bow to another: if you’re a student of a great master the greatest compliment you can pay your master is by finding your own voice. What the two had in common was that they didn’t imitate anyone else, they found their own way and they asked their own questions. Debussy has left us with this extraordinary homage to Rameau whom he revered, and it’s touching that it is so independent and strong. It shows the grandeur of Debussy that the only way he can pay homage to Rameau is by being entirely himself and showing how deep these roots go.

Víkingur Ólafsson (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC, Hi-Res+ FLAC

Víkingur Ólafsson (piano)

Available Format: 2 Vinyl Records

Víkingur Ólafsson (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC