Interview,

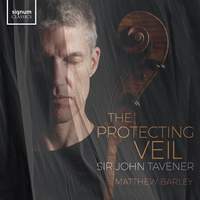

Matthew Barley on Tavener's The Protecting Veil

Cellist Matthew Barley's latest album sees him tackle John Tavener's mighty concertante work for the cello, the 45-minute The Protecting Veil – based on an eleventh-century legend about an apparition of the Virgin Mary, and reflecting Tavener's own Orthodox Christian beliefs with each movement focusing on a key event in the life of the saint.

Cellist Matthew Barley's latest album sees him tackle John Tavener's mighty concertante work for the cello, the 45-minute The Protecting Veil – based on an eleventh-century legend about an apparition of the Virgin Mary, and reflecting Tavener's own Orthodox Christian beliefs with each movement focusing on a key event in the life of the saint.

I spoke to Matthew about this monumental musical undertaking, and about the spiritual themes that Tavener weaves into his composition.

As a cellist, your concerto diet has presumably inevitably been dominated by the works of Schumann, Elgar and Dvorak, and other well-loved favourites. What first drew you to John Tavener’s music?

I remember when the piece was premiered in 1989, although I wasn’t actually at the concert, which was part of the Proms. It made quite a big splash in the music world; I was talking to someone the other day who’d been there at the premiere, and they said that a lot of the people in the audience that night had the sense that they were at the beginning of something special, that it was a very unique and powerful work. And word got around, and a couple of years later in about 1991, Oliver Knussen invited me to come and lead the cellos for the London Sinfonietta – I was just out of college at this point – and Christopher van Kampen was playing the solo part in The Protecting Veil, up at the Snape Maltings concert hall. I’d been doing a lot of work with the London Sinfonietta, working with a lot of very contemporary composers, but this was the first time I’d heard any Tavener, and I was completely blown away. It was a very extraordinary experience, unlike anything I’d played or been a part of before, and it was just so beautiful: the sheer vocal beauty of the piece just blew me away. I remember thinking that I really wanted to play this piece one day; I didn’t even dream, then, of recording it, so this is very special for me.

After converting to Orthodoxy in the ‘70s, Tavener gave expression to his new-found faith through a large number of sacred choral works, many of them drawing directly on the sound-world of Eastern Christianity. Why do you think he also chose the concertante cello as another vehicle to express his beliefs?

I never actually asked him about this, but I’m sure it must be because the cello is the closest instrument to the human voice: it’s got a similar range to the male and female voices and many people have that feeling about the cello, that it is able to sing like almost no other instrument. So I’m presuming that that’s why he chose it.

The enormous range is another asset; The Protecting Veil illustrates this very well right from the beginning, it’s right up at the very top. And it’s interesting the way John does that structurally; the beginning and end of the piece are right up in the soprano or violin register, and it sinks down into that long, meandering section in the middle, the Lament of the Mother of God at the Foot of the Cross, which is all on the C-string, right at the bottom of the range.

It’s a very unusual form; so often, pieces begin relatively quietly and work their way up to a climax at the end, or in the middle before dying down again. But this – to take it to that low point in the middle – is a very unusual thing and it’s often a point in the piece which people who’ve just heard a performance will comment on, that extraordinary empty solo passage in the middle. It’s really a song-based form; each section has a verse at the beginning where the cello introduces new material, and then at the end the orchestra joins in with these rather bell-like passages. In fact the orchestra are often playing all seven notes of the scale together, which creates these very tight clusters of notes, like rings of bells pealing away together madly. Each one of the sections follows that same shape.

The Sinfonietta Riga, who accompany you on much of this album, evidently share your own zest for musical exploration and the pushing back of boundaries; can you tell us something about your relationship with this ensemble?

This came about because I’ve been quite a regular visit to Latvia over the years, for various festivals there; the first time I played The Protecting Veil there, which must be six or eight years ago or so, that was with Gidon Kremer’s Kremerata Baltica, who were wonderful. Then there was another performance of this piece set up last year and the festival organisers suggested the Sinfonietta Riga. I was very keen; I’d heard very good things about them.

In addition, for this particular piece there’s a quality that you really need in the string players: a very deep, warm sound and extremely good intonation. And because they’re all from the Russian school of string playing, I could guarantee that I was going to get that quality. It makes a huge difference, even today. Most orchestras in Western Europe and America today, if you look down the list of names in the band, it’s like the United Nations! The players are drawn from all over the world, which has a real beauty to it. But in the Baltic states and Russia, almost all the players will be drawn from that country. In the Sinfonietta Riga I think there was one Finnish player and possibly a German, but all the rest were Latvian. The result of which is that they’ve all studied at the same school and they’ve all got that same sound; in this case it was extremely noticeable, and I loved that.

Among classical fans, who even today are still heavily concentrated in the “West”, the significance of Orthodox festivals such as the Dormition may not be immediately obvious. Do you think there’s a dimension to these deeply-felt religiously-inspired works that is lost on listeners of other faiths, or of none?

You might miss out on a layer in terms of the understanding of some of the ideas behind it. In musical terms, though, you won’t lose anything at all. Indeed, what makes this piece such a work of genius in my opinion is the way John has approached all these things and found the universal element to them. I think this is actually incredibly important; I often talk to audiences about this. When you get that solo section that we mentioned before, Mary’s lament, you have a woman on the ground in front of a large wooden cross which her son has been nailed to. You don’t need to subscribe to any religion to understand the extraordinary horror and full emotion of that situation. And it’s the same with all of these things; the Dormition is death, for instance, an endless sleep, and the Incarnation is that unbridled joy of being alive. I think it’s very very clever, the way he’s done it, because it stays true to his Orthodox faith, very much so – it really is a beautiful expression and celebration of that – and yet it’s completely accessible to all in the music. The music speaks to everybody with the universality of those themes.

John was fascinating when he spoke about these things; I did spend a very precious day with him about ten years ago, playing the piece and discussing it. I was struck by several things, one of which was how relaxed he was about the way different cellists played the piece; he really wanted people to just find their way with it. And I got the sense that he was listening much more to the spirit rather than to the actual notes – he didn’t care if this note was a tiny bit longer or a tiny bit shorter, he was listening to what was behind the note. And he said one very interesting thing: I asked him about the elements of Byzantine chant, because he wrote a footnote to the score for some of the ornaments indicating that they should be played in the style of that kind of chant, so I asked him what he actually meant by that. He was a little hesitant until I sang two options to him and asked him which he preferred; he instantly chose one of them, and I realised that it was much more like an Indian classical ornament, and John immediately said that this was exactly what he meant. Apparently he’d been listening to a lot of Indian classical music at the time when he was writing it. So I think that adds another layer to the universality of the piece, the fact that all sorts of different cultures have come into it – the end result is something that people respond to from the heart.

Are you aware of anyone else who mixes their religion with a “traditional” instrumental concertante style in this way, or is Tavener unique in drawing these elements together?

That’s quite an interesting question; the first person that springs to mind is actually Bach. He did take a few years off from composing sacred music in the middle of his career and there was that coffee-house where he used to go in Leipzig, and he wrote all those secular concertos; you wouldn’t exactly call them religious works, they don’t have those specific titles like the moments of The Protecting Veil, but I do wonder if he wrote soli Deo gloria on the scores, as with his other and more explicitly religious works.

Arvo Pärt is another one – very much a religious man who has written more secular pieces – and of course James MacMillan features very large in this area as well. I wonder how that works; the thing about The Protecting Veil is that the references to the religion are very overt, which in some ways sets it apart.

I’ve been very pleased, in my exploration of the piece, that in the end now that I’ve got to know it forwards and backwards I don’t feel that the religious aspect of it shuts anybody out at all, simply because of how it moves you as a listener.

You’ve always had an eye on innovation, whether it’s been working with Ensemble O/Modernt to draw unexplored musical parallels or performing cello recitals in unconventional venues. Where do you think your next recordings will take you?

There are three possible recording projects lined up – one is a completely solo project of all solo repertoire. There are all sorts of really interesting pieces around by composers like Brett Dean, Osvaldo Golijov, Mark O’Connor, Giovanni Sollima… probably twentieth-century, though possibly interspersed with Bach movements, I’m not yet sure.

There’s also another multi-tracked cello album bubbling away too – my first album was a multi-tracked one called Silver Swan – and the third one is going to feature cello and electronics, which is something I’m very involved in at the moment. So one of those three, I think. The electronics is fascinating: I’ve got a concert at Guildford University with some very, very beautiful pieces in it. There’s a professor from Kingston University, Oded Ben-Tal, who’s written a piece for me with quite a lot of foot-pedals involved, and effects whereby the computer is improvising with the cello; it has a microphone and the computer reacts to me in real time, and chooses its responses within certain parameters. It’s basically AI – it’s a fascinating area.

The Protecting Veil is released on 14th June on Signum Records.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC