Interview,

Clare Hammond on Mysliveček

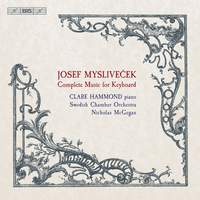

British pianist Clare Hammond’s small but distinguished discography is dominated by twenty-first century music, but for her fifth solo recording (released on BIS at the end of March) she’s stepped back almost three centuries to explore the complete keyboard music of the Czech composer Josef Mysliveček (1737-81); comprising two piano concertos and two collections of solo pieces for beginners, the album has already been praised for its ‘deliciously unfussy poise’ (The Times) and ‘sparky grace’ (The Guardian).

I spoke to Clare about Mysliveček’s friendship with the young Mozart, his colourful personal life, and the reception of his music in the twentieth century…

British pianist Clare Hammond’s small but distinguished discography is dominated by twenty-first century music, but for her fifth solo recording (released on BIS at the end of March) she’s stepped back almost three centuries to explore the complete keyboard music of the Czech composer Josef Mysliveček (1737-81); comprising two piano concertos and two collections of solo pieces for beginners, the album has already been praised for its ‘deliciously unfussy poise’ (The Times) and ‘sparky grace’ (The Guardian).

I spoke to Clare about Mysliveček’s friendship with the young Mozart, his colourful personal life, and the reception of his music in the twentieth century…

What set you on the trail of Mysliveček in the first place?

I was working with the flautist Ana de la Vega who had recently performed his flute concerto with the English Chamber Orchestra. She mentioned that there was a keyboard concerto languishing in manuscript form in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris and my interest was piqued!

Mysliveček was born and studied in Prague, and spent some years working in industry in his native country before relocating to Italy in the 1760s – do you see any traces of his Czech heritage in the music, or do Italian influences dominate?

I would say that Italian and German influences dominate in the keyboard music. The music that I have played, at least, adheres very much to a ‘pan-European’ aesthetic and I wouldn’t be able to identify anything that is inherently Czech. There is certainly no evident influence from folk music.

Following on from that, it was in opera that Mysliveček really made his name (and indeed much of the revival in interest in his music in recent years has focused on this body of work) – are there any operatic elements in his keyboard music, and is it fair to say that the operas eclipsed his work in other genres during his lifetime?

Again, I wouldn’t say that operatic influences are dominant in his keyboard music. There are more symphonic textures in some of the keyboard sonatas, where he uses rapid, loud octave figuration in the left hand, for example, but there isn’t the stylistic overlap that you get with Chopin, say, and his love of bel canto. Myslivecek’s operas were certainly the most successful of his works during his lifetime whereas the keyboard concertos do seem to have been neglected.

Mysliveček’s friendship with the teenage Mozart (and subsequent estrangement from the family) is well documented – do you see any traces of his influence over the young composer in Mozart’s own early keyboard writing?

Certainly, particularly in his two sonatas K. 309 and K. 311 which Mozart composed shortly after visiting Mysliveček in Munich in the autumn of 1777. You can hear that he has borrowed ideas from Mysliveček’s solo keyboard pieces and that the older composer was an important influence on him at this time.

Is it possible that the more scandalous aspects of Mysliveček’s private life contributed to the later neglect of his music, or were there wider political issues at play?

It is possible that his music was more swiftly forgotten after his death than might otherwise have been the case, but various factors have contributed to its neglect since then. In the mid-twentieth century, there was a drive among musicologists to revive less well known classical composers. Musicology itself was a relatively new discipline in the university environment and was based very much on a Germanic model, both in Europe and the States. As a result, there was a bias towards composers with German heritage, such as JC Bach and Gluck, while those from Eastern Europe were overlooked. Later on, with the rise of the Iron Curtain, it became more difficult for Czech scholars with an interest in this music to travel and disseminate their ideas. It is only really since the fall of the Iron Curtain that it has been possible to bring international attention to his music. It is certainly gaining ground now.

What sort of state were the manuscripts in, and how much work was there to do to render them performable? (I’m wondering about orchestration for the concerto in particular..)

The manuscripts were largely well preserved and legible, though there were a few missing corners here and there. I did have to reconstruct a bar or two when the ink had been smudged or the paper damaged. The main challenge, however, was deciphering his shorthand. While the scores contained almost all the information I needed, the notation was minimal and it took me a while to become familiar with the abbreviations he uses.

Clare Hammond (piano), Swedish Chamber Orchestra, Nicholas McGegan

Available Formats: SACD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC