Interview,

Dame Sarah Connolly on A Walk with Ivor Gurney

Many artists are marking the centenary of the 1918 Armistice by revisiting the music of composers who were directly affected by the war - some such as George Butterworth who never came back, and some such as Gloucestershire's Ivor Gurney who returned scarred and changed by their experiences.

Many artists are marking the centenary of the 1918 Armistice by revisiting the music of composers who were directly affected by the war - some such as George Butterworth who never came back, and some such as Gloucestershire's Ivor Gurney who returned scarred and changed by their experiences.

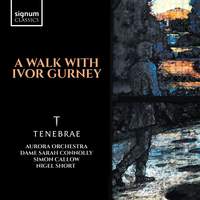

Gurney and his contemporaries are the focus of a new album that sees award-winning choir Tenebrae join forces with the Aurora Orchestra and mezzo Dame Sarah Connolly; I spoke to Dame Sarah about the fascinating mix of elegiac works on this album, and about Gurney's unique place within the history of English music in the twentieth century.

Despite the presence of some well-loved favourites, there’s much more to this album than just a selection of nice English pieces. A thread certainly links the works together, but exactly what it is is difficult to pin down in words. How would you describe the overarching theme of this album?

The thread is Ivor Gurney, his music and influence on those around him during his lifetime and now. Ralph Vaughan Williams was his professor of composition at the Royal College of Music, but he also became a good friend. Throughout Gurney’s lengthy confinement in the City of London Mental Hospital, Dartford, Vaughan Williams was one of a handful of people who consistently visited him. Several times Gurney escaped and ran to Vaughan Williams's house deeply distraught; with a heavy heart, Vaughan Williams returned him the next day. I often wonder what today’s treatment of Gurney’s bipolar disorder would be; his only wish was to be in the Cotswolds, walking day and night, and because this was disallowed, he decided never to go outside again. I find that desperately sad. The disc was made to capture some of the music performed at the Gloucester Cathedral Ivor Gurney window fundraising evening concert in August 2013 organised by myself. Philip Lancaster’s CD liner notes answer this better than I can.

You’ve studied Gurney in some depth, in particular writing your Master’s thesis on him; from your perspective, how far do you think Judith Bingham’s A Walk with Ivor Gurney succeeds in getting under his skin and capturing the essence of the man?

It wasn’t for a Master’s thesis, but an undergraduate one: it’s not too late, though! I think Judith’s collection of Gurney’s poems offers wonderful snapshots of the landscape, the topography that interested Gurney in Gloucestershire and Shropshire; there are many sites of Roman ruins and Bronze Age settlements which inspire imaginings and links to the past. Judith characterises these with modal echoed moving chords for the male voices, remote and formal, slightly ghostly sounding: "‘[T]he Romans were foreign invaders here, and we don’t feel the same sympathy for them as we do for the men in the trenches. And yet, on the tomb memorials found in Gloucestershire, one gets a sense of men stranded far from home, and of the gulf of time between them and us.’ Judith Bingham.

The solo songs were originally written with piano accompaniment, but you’re performing their orchestrated versions here. How much do you think this change of instrumentation alters their musical character?

As with all orchestrations, especially when the string sections are as fleshed out as they are here, singers tend to sing in a more legato style, broadening the voice to match the sound beneath. I think this benefits the songs which work equally well in a more direct, more ’spoken’ version with piano. Also, 'In Flanders' gets quite noisy in the orchestra, so one must give more voice to be heard! It is so wonderful that Stanford asked Howells to orchestrate these songs.

The sleeve-notes refer to the preponderance of composers brought up in Gloucestershire around the turn of the twentieth century – Gurney, Howells, Parry, Vaughan Williams and Holst, to name just the most famous. Do you think this is just a coincidence, or was there some common factor that helped nourish this particularly rich crop of musical talents?

The common factor was the wealth of poetry emerging from the First World War. British music was encouraged in many parts of the UK, and by the government. I think Stanford and Parry were hugely influential on the style of composition, and music festivals and cathedrals throughout Britain offered many performance opportunities: many of these composers earned their crust as cathedral organists at some point in their lives.

In addition to his musical compositions, Gurney was a poet of considerable eloquence; the text of Bingham’s Walk draws on several of his writings. How would you say his poetry relates to that of other, perhaps better-known, war poets (one thinks above all of Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen)?

The British poet, academic and journalist Roshan Doug writes very eloquently about this here: "Gurney did not write (like Owen) of ‘the pity of war’. He was not bitterly satirical like Sassoon, nor did he rage against the indifference of nature and landscape, as did Isaac Rosenberg and Edward Thomas. Instead, Gurney’s war poetry focuses on details and routine amid the chaos and horrors. In a letter dated 23rd February 1917, he writes of Severn and Somme, ‘I want… people to realise a little of what the ordinary life is’. References to friends, dreams, bread, butter, chocolate, smoking and other ordinary doings fill his poetry, because in the trenches it is the once familiar that is now resonant. Gurney’s focus is a counter-reaction to the destructive reality in which the soldiers found themselves. But this shift from the external to the internal world eventually heightened his awareness of his mental instability.”

A Walk with Ivor Gurney

Dame Sarah Connolly (mezzo soprano) & Simon Callow (narrator) Tenebrae & Aurora Orchestra, Nigel Short

A Walk with Ivor Gurney was released on Signum on 19th October.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC