Interview,

Edward Gardner on Walton

Edward Gardner and the BBC Symphony Orchestra have been wowing the critics for several years with a succession of recordings of orchestral works by William Walton. Previous instalments (the two Symphonies and the Violin and Cello Concertos) have shown Gardner's affinity for this repertoire, and now the final volume has been released - with the Viola Concerto, the Partita for Orchestra and the Sonata for String Orchestra. It's clearly an area that holds an immense fascination for Gardner, so I took the opportunity to quiz him further about this music, its historical context, and what it means to him personally.

Edward Gardner and the BBC Symphony Orchestra have been wowing the critics for several years with a succession of recordings of orchestral works by William Walton. Previous instalments (the two Symphonies and the Violin and Cello Concertos) have shown Gardner's affinity for this repertoire, and now the final volume has been released - with the Viola Concerto, the Partita for Orchestra and the Sonata for String Orchestra. It's clearly an area that holds an immense fascination for Gardner, so I took the opportunity to quiz him further about this music, its historical context, and what it means to him personally.

Hindemith, who first performed the Viola Concerto, was a prominent advocate and composer for this often-neglected instrument, and the booklet-notes allude to motivic hints of Hindemith within the music. How much influence do you think he had on Walton’s musical style?

There's something there, yes. There's this brilliant quotation about Walton that "you can never quite take him out of Oldham" [Walton's birthplace] - and for all his love of Italy and its exoticism and sensuality, there's always something craggy about his music, something under the surface that's a little bit gnarly. Of course that's taken much further with Hindemith, with music that is often so uncompromising, but equally with Walton there's something of that nature.

Walton never studied with Hindemith but there's a shared flavour on some level. I don’t mean this to sound pejorative, but for me Hindemith is more dogmatic and tightly-structured (emotionally as well as musically) whereas with Walton there's more freedom – that flavour is more of a layer under the surface. Of course the three concerti are all very different, but out of all of them the Viola Concerto is the one that has the most of that quality about it.

The Sonata for String Orchestra is, of course, a rearrangement of the earlier String Quartet, made by Walton with the help of Malcolm Arnold. How far do you think the character of the piece has changed in this new form? Do you think it constitutes a “new” work in its own right?

Well, I think there's something wonderful about the quartet version. That's how I first heard it and fell in love with that harmonic language - the wistfulness of the opening melody but also the rhythm of the scherzo. Of course there are still solo quartet passages within the Sonata itself, so that sense of chamber-music lyricism stays. But the rhythmic section, I feel, has much more in common with the First Symphony (especially its first movement), which is a piece I just adore. The coda of that first movement sits side-by-side with the scherzo of the Sonata, and there's something much more muscular about having this big string section performing it.

The ‘30s and ‘40s were a very rich period for string concertos, with Barber, Bartók, Britten, Korngold and Walton all producing successful examples. Do you think this is mere coincidence, or was there some common factor that drew composers of this period towards this particular form?

What you find, right up to contemporary music, is that there's a trend of one composer feeding on another and so forth. It takes us back to Berg's Concerto in 1935, really. In a way that piece is a reinvention of what the violin concerto can do on every level - emotionally and structurally, and with this huge orchestra. All the others are in comparison, or contrast, with that piece. There's something about both the Walton and the Britten that's unbelievably closely connected to the Berg, both in terms of reacting to it and in terms of its emotional content. Take the endings of both those concerti - they almost refuse to lie down, and that's so much like the extraordinary ending of the Berg. The wistfulness of the violin, maybe, was the voice of the era in some way.

Some performers have commented that string concertos of this period often pose a challenge in terms of lush orchestration potentially overwhelming the soloist. Did you find Walton’s revisions and parings-down of the Concerto’s scoring helped with balance in this respect, or was it never an issue?

You know, I grew up being told that the Viola Concerto is hard to balance - but in reality I think you have to just stick to what he wrote. It's extremely well written. The thing in this piece which is difficult to gauge is the tuttis: if they're overwhelmingly huge, sometimes when you come back to the soloist it can feel rather small-scale in comparison.

That's certainly not a problem with James's performance: both I and the orchestra were completely wowed by the quality of his playing. What you're hearing on the recording is real - it's not been closely miked or anything. He really can ride above the orchestra. But sometimes that is the very thing you have to be careful of: you want to embrace the mellow quality of the viola. It's about the colour of the piece, as much as anything.

You’ve recorded quite a lot of Walton in recent years – are you intending to carry on down this route, perhaps with Belshazzar's Feast or something similar, or is a change of direction in the pipeline?

Belshazzar's Feast is not one of my favourite pieces, actually! It's incredibly well-written but it doesn't lend itself to interpretation; it simply does its thing. It's not a piece that I can develop in myself by doing it over the decades. The lighter stuff isn't really for me; we've done all the concertos and the symphonies, and there are other people who can key into the atmosphere of the light works much better than I can.

My journey with this music really started with the First Symphony, with that great recording with the London Symphony Orchestra and André Previn. I can remember the first time I heard it - and it's been a voyage of discovery through that prism, really, which has led to many new musical finds for me. I knew the Viola and Cello Concertos but in fact the Violin Concerto was new to me until quite recently, and I really love it: when it's given the right flavour it has a very unique wistfulness. I'll always be performing his music, but in terms of recording it's probably come to a close.

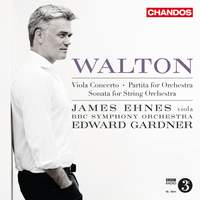

Walton: Viola Concerto, Partita for Orchestra & Sonata for String Orchestra

James Ehnes (viola), BBC Symphony Orchestra, Edward Gardner

The third volume of Edward Gardner’s Walton series was released on Chandos on 6th April.

Available Formats: SACD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Previous releases in the series

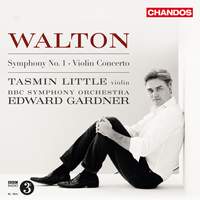

Walton: Symphony No. 1 & Violin Concerto

Tasmin Little (violin), BBC Symphony Orchestra, Edward Gardner

'Gardner and the BBC Symphony Orchestra profile the symphony’s turbulent syncopations, brassy dissonances and expressionist brilliance – a truly exhilarating performance. In the concerto, Little finds the nexus between sultry lyricism and rapturous virtuosity.' (Financial Times)

Available Formats: SACD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

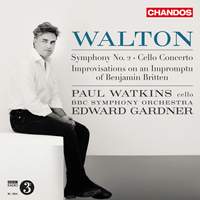

Walton: Symphony No. 2 & Cello Concerto

Paul Watkins (cello), BBC Symphony Orchestra, Edward Gardner

'On balance the greatest recorded performances of these three demonstrable masterpieces it has been my pleasure to hear…there is nothing egotistical in these splendid interpretations, and the result is a set of consistently satisfying performances of the highest musical grasp and understanding. I cannot imagine anything finer.' (international Record Review)

Available Formats: SACD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC