Interview,

Kirill Gerstein on The Gershwin Moment

As you may have noticed if you’ve glanced through this month’s Presto Editor’s Choices, Kirill Gerstein’s classy new album The Gershwin Moment has been occupying one of the top spots on my playlist for the past few weeks – until this recording landed on my desk in January, I’d associated the pianist with heavyweight Russian repertoire and Liszt rather than jazz or Americana, but the young Gerstein studied jazz in parallel to his classical training and his affinity with this music shines out in every bar of this thoughtfully conceived recording.

As you may have noticed if you’ve glanced through this month’s Presto Editor’s Choices, Kirill Gerstein’s classy new album The Gershwin Moment has been occupying one of the top spots on my playlist for the past few weeks – until this recording landed on my desk in January, I’d associated the pianist with heavyweight Russian repertoire and Liszt rather than jazz or Americana, but the young Gerstein studied jazz in parallel to his classical training and his affinity with this music shines out in every bar of this thoughtfully conceived recording.

I had a chat with Kirill recently about his own background in jazz, his thoughts on changing perceptions of Gershwin in the United States and further afield, and the composer’s remarkable facility for absorbing the sound-worlds of both popular music of the 1920s and 30s and the late Romantic and Second Viennese School composers whom he so admired.

Which particular jazz musicians inspired you when you were young, and when did you first start exploring Gershwin’s music?

I listened to a lot of jazz recordings from an early age: the one that I specifically recall is the Oscar Peterson and Dizzy Gillespie duo album [from 1974], but the rest is lost in a jumble of childhood memories! But in some way that early exposure made me resist playing it myself for a long time: when I started building up my own background in jazz, I consciously decided to save Gershwin for later! I think the Rhapsody was something I learned about ten or eleven years ago and the Concerto five years ago, but the idiom certainly feels comfortable.

You studied jazz formally in parallel with your classical training: how much does your background in this music feed into your approach to classical repertoire, and vice versa?

Who knows?! Certainly in terms of the current recording, very much so. I think it’s also true more generally but in ways that are hard to identify or specify: in a sense it’s like trying to think about how much speaking German feeds into the way I speak in English and Russian. But having had exposure to such a significant musical language and idiom definitely seeps into other things that I do – there’s a certain way of working with harmonies which jazz brings, a certain feeling of freedom. I think it’s very important to experience the feeling of music not necessarily just coming from the written page, not being something that you just read and learn: that’s more about improvising than about jazz specifically, but I’ve mainly experienced improvisation within the jazz idiom. The other important thing is that within the jazz style there’s a certain expectation of bending musical time, a sense of flow of time and accents within the music. And that level of metric pleasure should also be felt in a Beethoven or Rachmaninov or Bach piece; that’s something that was very clearly illustrated to me by jazz, but also by my Hungarian mentor Ferenc Rados.

Do you see any kinship between Rhapsody in Blue and other early twentieth-century works for piano and orchestra?

I certainly do. On the one hand Gershwin is trying to bring together so-called ‘classical’ and so-called ‘popular’ music - and he was one of the most successful ones, because this marriage of the two doesn’t always work out so seamlessly. But in another way, he’s very much showing that he is familiar with all these other examples of grand Romantic pieces: I find there are moments where he is mentally in Tin Pan Alley and writing something that could be for a Broadway play, and then he’ll turn and say ‘But I know how to write in the style of Tchaikovsky! I know all the piano figurations of Franz Liszt, and I know Rachmaninov’s music…’ I find that very charming, very endearing: it adds to the impression that this is really a piece by a young man who not only wants to show how excellent he is, but also how excellently he can write in the style of other people.

I think by the time we get to the Concerto in F he is very much paralleling some developments in the 1920s and 30s in terms of writing for piano and orchestra. We know that Gershwin was interested in the music of Alban Berg and Arnold Schoenberg, so in some ways it’s just how you turn the angle of the kaleidoscope: there are moments where you think ‘Well, this could come from jazz, or it could come from his love of the contemporary European composers’. It’s also important not to underestimate how influential Liszt remained in terms of the way people were writing for the piano during this period; by the 1920s and 30s you have Ravel, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Rachmaninov and Gershwin all putting their own individual stamp on what are still essentially Liszt’s inventions and innovations.

How different is the jazz-band version of Rhapsody in Blue (which we have on the album) from the Grofé orchestration, and do you have a preference for either arrangement?

On the CD we have the band version, which is far less frequently recorded than the orchestral one (even though the piece was actually premiered in the band version). I think it is quite different, because it’s tighter, it’s jazzier; I find it allows for more freedom in terms of rubato and phrasing, so I much prefer this version to the full symphonic one.

Do you feel that perceptions and reception of Gershwin’s music have altered within your lifetime?

I think the general perception has changed (as Joseph Horowitz stresses in his booklet-essay, which I like very much), especially in the United States; I think in Russia he’s always had a steady popularity and exerted a certain attraction, partly because it’s seen as an American thing. But in America things have shifted really quite recently: I am told that the Rhapsody in Blue, the Concerto in F and An American in Paris weren’t programmed on the main subscription series until the late 90s and early 2000s at major US orchestras such as the Boston or the Chicago Symphony! There’s become less of a stigma around programming Gershwin as a so-called ‘serious’ pianist-composer, with a major orchestra; I think twenty years ago that was something you’d see rarely, and forty years ago even more so. It’s interesting to look at the discography of the Piano Concerto and Rhapsody in Blue, because you don’t see that many American pianists featuring the piece between 1930 and 1970 or 80 – there’s Earl Wild, and Oscar Levant and a couple of others.

Could you tell me a little about your history with your two guest collaborators, Gary Burton and Storm Large?

Gary has played a seminal role in my life because I met him when I was 12 really by chance: I was backstage at a jazz festival in St Petersburg and I was the only one there that spoke English, so I ended up translating for him. (He wondered as to what a 12 year old was doing backstage at a jazz festival after midnight?!). He asked me to send a recording of my playing, and to cut a long story short I ended up coming to Berklee at his invitation, because Gary was the Vice-President of the Berklee College of Music as well as being an internationally renowned jazz performer. So he was really the one who brought me to America and I was fortunate enough to have the most incredible lessons with him. When I went off and continued my classical career we stayed in touch and did some projects together: there is a piece which I commissioned from Chick Corea with my Gilmore funds [Gerstein was the recipient of Gilmore Award in 2010] and we premiered that together, and then there was a concert that I did at Berklee (returning to one of my alma maters) where we played the Chick Corea piece as well as Oscar Levant’s “Blame it on my youth”(which is on the new album).

I met Storm Large when she was at the Gilmore Festival some years ago, singing with the Pink Martini band. Before one of their songs they announced from the stage ‘Oh, we need somebody to play the opening melody of Schubert’s F minor Fantasie’, and nobody was volunteering, so eventually someone pointed the finger at me… I got up on stage and got to sit in with the band on that arrangment, and that was how the two of us met! Then when I was performing in Portland Oregon, which is where she lives, I called Storm and said ‘Now I’m turning the tables! I’m playing Rachmaninov with the Oregon Symphony, you’re in town… we’re going to do a surprise encore!’ (At least I noticed her before the concert!). So after the concerto I took the microphone and said ‘Well, I will do an encore - but I’ll need some help from somebody who lives in your town…’ When Storm came on stage, the place went crazy because she’s a local hero, and we did Summertime together. That evening gave us the idea of putting together a whole cabaret programme of songs, and in fact the Summertime on the album is from a live set we later did at the Gilmore festival.

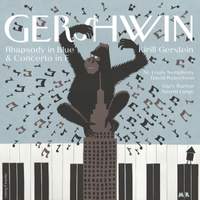

The Gershwin Moment

Kirill Gerstein (piano), Storm Large (vocals), Gary Burton (vibraphone), St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, David Robertson

The Gershwin Moment was released on Myrios on 23rd February

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC