Interview,

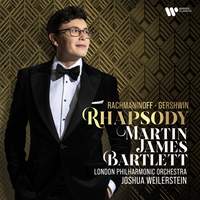

Martin James Bartlett on Rachmaninov and Gershwin

BBC Young Musician winner Martin James Bartlett has a long relationship with the luscious works of Rachmaninov and Gershwin for piano and orchestra - both composers have featured in major milestones in his fast-moving career.

BBC Young Musician winner Martin James Bartlett has a long relationship with the luscious works of Rachmaninov and Gershwin for piano and orchestra - both composers have featured in major milestones in his fast-moving career.

It must have seemed natural to pair the two composers up on an album, but in doing so Bartlett found that the links between them ran far deeper than he'd realised, creating an album "of two halves" that captures not just the differences of mood between these works but also the profound similarities that they share. He also digs into the legacy of the other musicians who formed a bridge between the two great composers - band-leaders, arrangers and virtuosos at the keyboard.

I spoke to Martin about this album, entitled simply Rhapsody, and the web of connections that holds it all together.

Given that they were only composed a decade apart, do you see any similarities between the two Rhapsodies that form the main works on this album?

I think certainly there are similarities between the works; an especially interesting element is that they’re both rhapsodies and are very episodic, with many different sections and relationships between them. If you think of the famous Variation 18 from the Rachmaninov, with the clever inversion and augmentation (and transposition into a different mode and key) of the original motif, I think that is related to the Gershwin in that the latter’s middle section has a slow melody that is again a different “take” on a musical idea from elsewhere in the piece. So in that sense they have a clear compositional similarity.

What makes them even more similar is the Grofé orchestration of the Gershwin, which makes it very sweeping and luscious, full of symphonic depth. In that sense it’s different to the jazz band version. One of the things that I loved about this album was the connections between all the composers – Rachmaninov was a big fan of Paul Whiteman, the bandleader for whose band the Gershwin Rhapsody was originally written, and he attended the premiere, so he heard the first performance of with Gershwin himself at the keyboard. Then, ten years later, he composed his own Rhapsody.

There’s also Earl Wild, who is the joining-point of these two works – a great virtuoso pianist himself and also a transcriber, who I discovered had transcribed not only Gershwin but also Rachmaninov. You wouldn’t believe how delighted I was to find that he’d done both, because it tied in so perfectly with the plan. And it was Earl Wild who gave the premiere of the second of Grofé’s two orchestrated versions, with Toscanini conducting. Earl Wild, in turn, knew Rachmaninov; he’d been to his song recitals and had heard him play these songs.

So in that sense, in New York at this time, it was this meeting-point of all of these different influences, especially with jazz. That’s how I tie it together, and the midpoint is the Rachmaninov polka. This isn’t a transcription – it’s the original version – but the wonderful thing about it is that it’s dedicated to Godowsky, of course another great Russian-American transcriber and virtuoso pianist, and it’s at that point that the album moves from the Rachmaninov – heavier and deeper and so on – towards the slightly lighter whimsical jazz side leading to Rhapsody in Blue.

Rachmaninov was at the first performance of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue; is there any evidence of direct influence of that experience on him, or even simply of how he reacted to it?

I don’t actually know the answer to that – all I know from the literature I’ve come across is that he was there. Whether he smiled or grimaced – I can’t tell. But personally, I’m sure that he would have found it terribly good fun, especially with the Paul Whiteman Band. I would love to have been a fly on the wall in that kind of situation.

These are both important pieces for you personally, that you performed in the BBC Young Musician final and in your Proms debut; has your perspective on them shifted since you were very young?

Yes, the Rachmaninov was the piece that I won BBC Young Musician with. I would say I’ve grown with these pieces a lot; I have a very strong fondness for the Rachmaninov as the piece that kick-started my career, and naturally as I’ve got older I’ve played it slightly differently. Tempos and things shift as a piece evolves with you. And the Gershwin most definitely – since playing it at the Proms I’ve discovered all the recordings of Gershwin himself playing it with the jazz band. It takes it in a very different direction from the big symphonic sound – something that’s not quite so luxurious and decadent. A bit more cutting, if that’s the right word; it’s a case of striking the balance between the symphonic element and the need to keep it “real”, so to speak. It’s a jazz piece with a lot of impetus and momentum. And that’s what we aimed to do with Joshua Weilerstein, who’s conducting on the album – to get that sense of perspective on both recordings.

Do you have a strong jazz background yourself?

I very much have a love of jazz; I’ve spent a lot of time in Ronnie Scott’s listening to jazz bands, I have it on a lot in the background at home. And of course I love musicians like Art Tatum and Oscar Peterson. Personally I don’t play any jazz, but what I love is the coming-together of the jazz and classical genres, and making sense of it. It’s quite a hard thing to pull off, like when opera singers move into singing musical theatre. Someone who does that terrifically is Renée Fleming, and I take quite a lot of inspiration from her in terms of how to keep this classical structure and style, but also get the witticism that jazz is full of.

Do you fancy the idea of a solo recital of rhapsodies - what might feature in such a programme?

Potentially yes, you could do a solo recital of rhapsodies; one thing that’s wonderful is the solo transcription of Rhapsody in Blue, which is an amazing feat as you have to incorporate all the orchestral elements. And there are the Liszt Hungarian Rhapsodies, and so many others. But an idea that really appeals, which I’ve done a bit of already, is a programme of transcriptions, which are something I love, and especially operatic transcriptions. So again there’s Liszt’s transcriptions from Tannhäuser, from Rigoletto, from Tristan und Isolde, and things like Grainger’s Ramble on Love, based on Der Rosenkavalier. One could definitely do a programme not so much entirely of rhapsodies as such, but centred on rhapsodic pieces as a concept.

Gershwin, Rachmaninov and Earl Wild were all superb virtuosos - does their writing for the piano give any hints as to their different technical strengths and preferences?

I think so. You can tell, perhaps, from the Rachmaninov that he was a very nervous pianist. There are many stories about him being nervous, and famously the reason that he wrote the beginning of his Second Piano Concerto in that way – first slow chords, then passagework that’s concealed by the string melody – was to warm up his fingers so that when the part became exposed, he would be ready! And it’s the same in the Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini; partly because the piece just has to be constructed that way. The clever thing there is that he builds up the variations very gently. It starts with the theme in a form you could play with just one finger: A, E, E, A. Then you add in some of the filigree in-between, and it gets complicated from there on. This is also why everyone can play the first two pages of his Third Piano Concerto – and it’s for the same reason. A nice way for him to ease into a concert.

This is something I like to do myself; I love starting concerts with Bach transcriptions that are quite beautiful and gentle, because it’s a way of warming your fingers through. And you save the Prokofiev or Ravel, say – the big, virtuosic works – for the end. So in that sense you can definitely see the pianists’ influence.

Likewise with Earl Wild, you can definitely see from the way he distributes the material between the hands that he was an incredibly virtuosic, but also clever, pianist. Someone who knew how the physiology of the hand worked and how to make things fit beautifully under the fingers. Gershwin is slightly more awkward, but I think it’s that way because of the improvisatory style in which he wrote it. He wouldn’t necessarily have felt the way it feels under the hand, as it would have been more spontaneous at the time. But you can tell that all three of them were immense musicians.

Do you have any direct connections back to either composer, in terms of the people you’ve studied with?

I do. My second teacher (after my mother, who first taught me) was a lady called Emily Jeffrey, and she had spent some time playing for Jorge Bolet, the brilliant Cuban pianist. He was very much of the same kind of virtuosic school as Rachmaninov and Earl Wild, and he’d studied with Godowsky (to whom Rachmaninov’s polka is dedicated), who had in turn studied with a pupil of Czerny, who of course had studied with Beethoven. So that’s a lineage I can trace – in a way, it’s almost terrifying to think about it!

Why did you choose these particular solo pieces to complement the two major Rhapsodies?

Some of them I’ve been playing for quite some time; The Man I Love has always been an encore for me. This album is actually dedicated to my grandmother, who died in the middle of recording – and she loved Gershwin and these kinds of things, so every time I used to visit her I would play The Man I Love. I wanted to include some solo works on the album, and I played Earl Wild’s Embraceable You, which I’ve been playing for a long time too – and it was through discovering more about Earl Wild that I realised he’d also done these remarkable transcriptions of Rachmaninov, and it seemed like the perfect meeting-point in the middle of the album to have these two great composers transcribed by another fellow American who has been an inspirational pianist to me for a long time.

And I think the album flows quite nicely through from that terrific opening of the Paganini Rhapsody that instantly grabs you - six notes from the orchestra and the piano comes in with a huge crashing bottom A in octaves. It's such an awakening, and yet the way the piece ends is so cheeky. And then we go into the Vocalise, which is just such a different sound-world, and through to Where beauty dwells, and the Polka is the point at which things start to be a bit "funnier", after which the second half is lighter. Not lighter in weight, of course, but in the sense of brightness. When I found the transcriptions, I thought how perfectly it worked - bookending the album with these two Rhapsodies, and in the middle having all of these great, fun pieces that I love in their own right. They're a bit like a section of encores.

Did you ever think about doing the two Rhapsodies in the other order?

There was lots of thinking and planning of the elements in this album, but that idea of going from East to West was important (mirroring the direction Rachmaninov himself travelled), and from classical to jazz at the same time. I don't want to sound too flippant, but "serious" to "humour" was an important journey. We even tried to encapsulate that in the album-cover - the front cover is relatively strait-laced, and I have the normal bow tie and jacket, and then on the back the bow tie is undone, the shirt is slightly unbuttoned and I'm laughing and looking a bit more relaxed. So the whole album - from an artistic as well as a musical point of view - was trying to show that journey.

Martin James Bartlett (piano), London Philharmonic Orchestra, Joshua Weilerstein

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC, Hi-Res+ FLAC