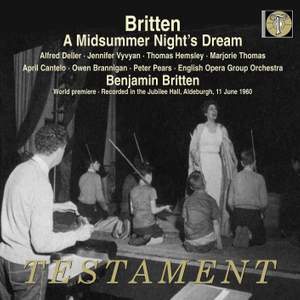

World premiere, recorded in the Jubilee Hall, Aldeburgh, 11 June 1960 First ever release.

At first glance, Britten’s discography of his own operas leaves little to be desired. His recorded legacy covers practically his entire output in recordings under his own direction, with his favourite artists, produced to still-legendary standards. And yet, as magnificent as the official recordings are, many do not feature the singers who created important roles; and sometimes even when the interpretations do come from the source the published versions are from a few crucial years downstream. A Midsummer Night’s Dream is no exception. It was composed at breakneck speed for the reopening in 1960 of Aldeburgh’s Jubilee Hall, a tiny theatre by operatic standards, seating just over 300. It would soon move to the rather more capacious Covent Garden (and for that matter within the following year to Hamburg, Zurich, Berlin, Pforzheim, Milan, Vancouver, Gothenburg, Edinburgh, Schwetzingen and Tokyo) – finally reaching a commercial recording in 1966 under very different circumstances from those in which it was created. Perhaps the greatest single asset of the 1960 recording, though, is the chance to hear Alfred Deller’s very earliest performance as Oberon. Deller’s inclusion in the cast was one of Britten’s most original inspirations: nowadays counter-tenor roles are an essential part of the operatic palette in old and new music alike and gifted singers to sing them are plentiful, but just a few decades ago a counter-tenor was an exotic beast indeed. Sir Michael Tippett wrote of first hearing Deller’s voice: ‘In that moment the centuries rolled back’. For us, half a century and more already rolls back when we hear Deller in A Midsummer Night’s Dream: Deller’s voice is ironically now a historical phenomenon in itself.

Britten’s own interpretation of the opera would broaden over the years. Here the ink on the score is barely dry and some passages are unforgettably urgent: Oberon and Tytania’s opening duet has a compelling sweep, and the Act II quarrel of the lovers has an extra tinge of danger. The glorious choruses which end the second and third acts would certainly be given more time in later performances, but not always either to their benefit or to the advantage of the whole: ‘On the ground, sleep sound’ is all the more poignant if it, as here, never becomes static, and Puck’s epilogue can sound a little tacked-on if ‘Now until the break of day’ is allowed to wallow. Fortunately, there is no need to choose. We are all the richer for having two such distinct approaches to the opera in its early history at our disposal and since they both come direct from the composer himself, perhaps the not always helpful concept of a ‘definitive recording’ can usefully be called into question.

Artists

Alfred Deller (Oberon), Jennifer Vyvyan (Tytania), Leonide Massine II (Puck), Kevin Platts (Cobweb), Robert McCutcheon (Mustardseed), Barry Ferguson (Moth), Michael Bauer (Peaseblossom), George Maran (Lysander), Thomas Hemsley (Demetrius), Marjorie Thomas (Hermia), April Cantelo (Helena), Forbes Robinson (Theseus), Johanna Peters (Hippolyta), Owen Brannigan (Bottom), Norman Lumsden (Quince), Peter Pears (Flute), David Kelly (Snug), Edward Byles (Snout), Joseph Ward (Starveling)

London Symphony Orchestra, Choirs of Downside & Emanuel Schools, Benjamin Britten