Interview,

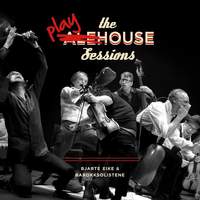

Bjarte Eike on The Playhouse Sessions

After the resounding success of 2017's roistering Alehouse Sessions, perhaps it was inevitable that Bjarte Eike and his Barokksolistene would return to the unbridled atmosphere of musicmaking in Restoration London - this time focusing on the flourishing of "pub theatres" that emerged to meet the huge demand for live performance after the fall of Cromwell's puritanical Commonwealth.

After the resounding success of 2017's roistering Alehouse Sessions, perhaps it was inevitable that Bjarte Eike and his Barokksolistene would return to the unbridled atmosphere of musicmaking in Restoration London - this time focusing on the flourishing of "pub theatres" that emerged to meet the huge demand for live performance after the fall of Cromwell's puritanical Commonwealth.

A foray into Shakespeare in the intervening time, in the form of a Norwegian production of A Midsummer Night's Dream in late 2019, has only heightened the group's appreciation for English early music and its cross-pollination with folk music.

I spoke to Bjarte about the Playhouse Sessions, his approach to genre-blurring innovation, and why this moment in musical history is so important to him.

This album follows in the footsteps of your acclaimed Alehouse Sessions from 2017. Was it always your plan to record a theatre-focused second volume?

The Alehouse project has had a lot of attention - both the recording and certainly also the live shows. The question “when is your next album coming” has been asked numerous times and I’ve been looking for a way to keep the Alehouse project alive and kicking. It’s an ever-evolving project, and more like a musical laboratory where we constantly explore new repertoire, new arrangements/compositions and different approaches to presenting the live show. All the music we perform has gone through this laboratory in order for us to come up with versions that are distinctly our own.

But at the same time, Barokksolistene and myself are doing so many other projects alongside the Alehouse, with a special interest in staged productions where we are on stage and part of the action (opera, theatre and ballet/dance). I’ve also had a special interest in Henry Purcell’s incredibly versatile and rich music - I really see him as the Shakespeare of music. So I wanted the next album to reflect on all this: to incorporate experiences and repertoire from our staged productions, with music by Purcell, and of course new Alehouse material. So, instead of merely calling it ‘Alehouse vol.2’ I wanted to expand and build on the narrative with the pub-sessions - moving from the bar area, and out into the backroom where we would enter the provisional stage and perform our show.

The promotional video for the original Alehouse Sessions

There’s clearly a strong folk influence on your approach here. Do you think there’s more of a folk element to early music than current performances tend to admit?

I’ve always seen the strong connection between what we know as folk music today and the music in the baroque era. First of all, ‘baroque’, ‘renaissance’ etc. are expressions connected to periods in time, when certain tendencies within arts, architecture etc. were predominant, and these generalisations help us modern people to classify these periods. But it’s still just a time-period, and the types of music found then were as versatile as today, and was often composed for special occasions (weddings, church ceremonies, funerals..etc…)

So, music written for church masses, vespers, coronations etc. would not be included in my Alehouse or Playhouse programs (although you’ll find lots of church music using dance rhythms, familiar (folk) tunes etc.). Instead, I will look for music that was used in theatres, for dancing, and on the streets - tunes found in collections of popular folk melodies or songs that have a particular story or narrative connected to them. As mentioned above, I also have a particular interest in Henry Purcell, and find a lot of his folk-tunes or bawdy songs are often done too properly. I think a more folky approach to SOME of his music only helps to discover just how versatile and brilliantly he moves around musical styles and influences - nobody else in music history can go from composing such splendid church music to brilliantly theatrical music to such spectacularly rude songs.

Having said that, I think it is important to point out that my, and Barokksolistene’s interest lies in how we perform and present the music in our shows. We combine own arrangements, own compositions with lots of improvisations and humor. We thrive on incorporating theatrical elements and always invite our audiences to join in on the party. Therefore, our music does perhaps become distinctly our own. So for people used to classical or early music, it might sound “folky”, whereas for folk-musicians it may sound more “classical”. I like to think there are only two types of music: good and bad. And quoting the great Louie Armstrong: “all music is folk music - hell, I ain’t seen no horse sing!”

You pose, and deliberately refrain from answering, the question “what genre is this?” Clearly no single label fits. But if you had to say what genres go into the mix, what would you say were the main influences?

I have partly elaborated on this in the previous questions, but I think a main point is that we try to create - as much as interpret - music, even if we mostly use old melodies. We take inspiration from early music rooted in historically informed performance practice (obviously), various styles of folk-music (both old and contemporary), musical theatre (type of repertoire and ways to execute the music) and a general, modern approach to music through a high level of improvisation (using your own experiences to interpret music). I will always dive into any kind of music that interests me with a playful, curious and not too serious approach.

So, what genre is it? Well, a sort of musical theatre of baroque and folk melodies pimped up to delight a 21st century audience member!

The atmosphere you’re seeking to invoke here is one of a post-Cromwellian pub theatre – informal, light musical and theatrical entertainment. How long did these theatres survive, and what happened to them?

It’s sort of blurry - playhouses were built really fast after the Restoration, but they couldn’t build them fast enough to meet the demand, and both the alehouse, and playhouse sessions continued well into the 18th century. There are four famous major Restoration theatres that arose immediately after Charles II returned. The Cockpit Theatre, Theatre Royal (Drury Lane), Dorset Garden and Lincoln’s Inn Fields. But these had major challenges in the beginning as well - not least because of the Great Fire in 1666 (!). The Lincoln’s Inn was originally a tennis court and was rather small and poorly furnished. It wasn’t really turned into the splendid version that became famous for hosting John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1727) until 1714. Of course, Lincoln’s Inn relocated to Covent Garden in 1732.

But, again, it’s important to state that our album is not a museal project, trying to recreate and present the music and how it would have been done in these public houses, but the historical events and factors create fascinating and inspirational backdrops for us to be inspired by, and to play off on.

Your ensemble is mostly made up of Scandinavians – how did this particular moment of English history become such a source of inspiration for you?

Well, we have two very British members in Steven Player and Thomas Guthrie, but speaking for myself, I’ve always been a bit of an anglophile. I lived in London for a short time, have worked in England many times and know more Monty Python quotes than many British people. I am a keen follower off the Premier League and love the idea of people giving directions based on the number of pubs (“after the third pub, turn right”…), the energy that combining politeness, sharp wit and sarcasm brings, BBC public service…

When a festival that I was curating in Norway came up with the theme “London around 1700”, it was really a lot of fun to start digging into the history. Programmes on Handel and the Italians in London emerged, as well as a Dowland project to explore the melancholic time around 1600 (and connecting that to the Nordic Noir elements found in the Scandinavian folk music), and of course I had to do something connected to what the British would call their second home - the pub. I started with a collection I had acquired some time earlier, John Playford’s “The English Dancing Master” made up of simple melodies that I started harmonising, arranging and compiling into sets. Catchy stuff. Well, then I wanted to know where these melodies would have been performed, and before long I had lots of literature on the origins of the English drinking houses. And a whole new world opened up for me… a world that I’m still exploring and keep being fascinated by today (hence the release of this album).

You’ve included the swaggering Hey Jolly Broom Man as a tutti number on this album – how much audience participation would there have been in the kinds of performances that these pub theatres hosted?

I haven’t really come across any details on how things would have been performed, but I would expect a lot of audience participation. Remember that there was alcohol involved... and that the well-behaved audience that we know from our modern classical concert halls (shushing on each other when coughing or applauding between movements) is very much a 20th century thing. But with the sheer numbers of pub songs and sea shanties etc. that have survived, there is no doubt in my mind that there would have been plenty of sing-alongs in the back rooms of the pubs.

Even after two Sessions albums, there must still be an enormous volume of music available to draw on for projects of this kind; are there more sessions planned after this one?

I have several projects in the pipeline - a few more “sessions” included. But have to say that assembling this album has taken quite a bit of effort, so I want to dwell a bit on this album - spend some time developing the live versions of the Ale-Purcell-Playhouses further. There is also a second release of this album on LP and in Dolby Atmos planned for January/February next year (the delivery time for vinyl is really slow these days).

On perusing the sleeve notes to the album, my colleagues and I were fascinated by the allusion to guitarist Fredrik Bock’s “famous emergency egg”. Can you tell us more about this mysterious artifact?

The emergency egg is famous within our band (not necessarily outside our small circle), but Freddy always picks up a hard boiled egg from the hotel breakfasts and brings it with him in case he isn’t able to find food again for more than 3 hours. So, an egg for emergencies. (Once he left the egg in his pocket and then boarded a plane… when landing it was not in the shape of an egg anymore… and unluckily, it wasn’t originally hardboiled either…)

Barokksolistene, Bjarte Eike

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Barokksolistene, Bjarte Eike

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC