Interview,

Sandrine Piau on Handel's Enchantresses

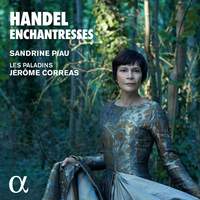

I think Sandrine Piau's spellbinding 2004 recital Opera Seria on Naive was the first all-Handel vocal disc I ever purchased, and its successor Enchantresses (released last month on Alpha) works an equally potent magic, with the French soprano's insouciant coloratura, keen characterisation and range of vocal colour remaining every bit as captivating almost two decades later. It was a rather special pleasure, then, to meet Sandrine over video-call a few weeks ago as she prepared to set off for London and Wigmore Hall, and to enjoy her warm and witty company as she discussed her rather unorthodox route to a solo singing career, the conductors and stage-directors who've informed her approach to this repertoire over the decades, why bel canto isn't for her - and how some Parisian joggers got rather more than they bargained for in a twilit wood one evening last year...

I think Sandrine Piau's spellbinding 2004 recital Opera Seria on Naive was the first all-Handel vocal disc I ever purchased, and its successor Enchantresses (released last month on Alpha) works an equally potent magic, with the French soprano's insouciant coloratura, keen characterisation and range of vocal colour remaining every bit as captivating almost two decades later. It was a rather special pleasure, then, to meet Sandrine over video-call a few weeks ago as she prepared to set off for London and Wigmore Hall, and to enjoy her warm and witty company as she discussed her rather unorthodox route to a solo singing career, the conductors and stage-directors who've informed her approach to this repertoire over the decades, why bel canto isn't for her - and how some Parisian joggers got rather more than they bargained for in a twilit wood one evening last year...

Is there a connection between Enchantresses and your previous album Clair-Obscur?

These two recordings have the same story – something beautiful created out of adversity. We recorded Clair-Obscur two days before the first lockdown in France, and Enchantresses right before the second one; we also lost two hours of recording-time because of a fire in the building, and most of the musicians couldn’t stay on because they needed to get home in time for the lockdown. Jérôme [Correas] said ‘OK, we’ll just record Lucrezia with you and continuo’; it was a very intimate, moving experience, and I think having this strong woman virtually alone at the heart of the recording works very well.

Did you originally plan to record the entire cantata?

I’ve sung the whole thing, but I couldn’t imagine it sitting well on this recording. This particular aria is so beautiful and strange: we chose to record it with a lot of dramatic silences and space around the sound, like somebody singing in the bathroom while cutting their wrists.

As with all my recitals, I try to tell my own story through different stories and characters: I’m fascinated by the contrast between light and darkness (hence Clair-Obscur), with the opposition between dreams and reality (which I explored on Chimère) and with the obsession with power, and this album draws all of that together. I don’t believe in God, and I know I’m born to die (perhaps music is one of my means of coming to terms with that), but I do believe in moments of magic and transcendence: I remember singing ‘Ah mio cor’ in a wonderful staging of Alcina and feeling as if time had stopped and we were hovering somewhere between immobility and immortality.

I sing both roles in Alcina, but I have to confess that I really warm to Morgana. We included her here because both she and Alcina are monsters in their own way, and we chose ‘Tornami a vagheggiar’ partly because Alcina sometimes steals it: we really liked the idea of this diva who has twelve arias but will still steal from Morgana who has four! It’s such a perfect representation of this particular enchantress – she’s a nasty girl!

Alcina and Morgana are quite literally 'enchantresses' in that they practise sorcery – how do the other characters on the album weave their spells?

The idea behind Enchantresses wasn’t just about magic, and perhaps that’s clearer in the French language - we spent hours debating whether the title should be in French or in English! Some people insisted it had to be English because of Handel’s strong English identity, but my preference was for the French because that means something quite different: an ‘enchanteresse’ is simply ‘one who charms’, whether that be through magic or simply through seductive powers.

So not all the characters here are magical women. Cleopatra and Adelaide in Lotario aren’t sorceresses, but they exert their own power and fascination; Almirena in Rinaldo is a victim with no power at all, but in ‘Lascia ch’io pianga’ she works such magic through music. She’s not an enchantress as such but l’enchantement emanates through her voice in that aria, and that’s why we decided to end the album with it.

Was baroque opera always something that attracted you?

No! I originally studied as a harpist, at the Conservatoire de Paris, so I rarely listened to baroque music at all. Harp students earn nothing, so I sang in Philippe Herreweghe’s choir to get money; one day I met a flautist who said ‘I know you’re earning money through singing, Sandrine, and there’s a conductor here who runs a class you might want to apply for – if he likes what you do, he might get you more work!’. That conductor was William Christie! I auditioned and was successful, and it was a very busy time; I started studying with William in 1985, and in 1989 I did my first Fairy Queen with him at Aix-en-Provence. That was also around the time of my final exams, and I remember telling him that I found singing too nerve-racking and was going back to the harp…I felt so natural being part of a choir, but thought singing as a soloist wasn’t for me. William said ‘OK, I’ll call you in a year and we’ll see!’.

The next year I went back to Aix for Les Indes galantes, and finally I felt more comfortable. I could imagine singing in this kind of opera: small parts, comic things, with nice staging so you forget you’re singing! Then we did Castor et Pollux, and in 1991 (my last year at Aix) I saw this wonderful Robert Carsen production of Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. And I cried, because I couldn’t imagine ever singing that music: because I’m French, because I’m a baroque singer… 26 years later I sang it in Aix, with Carsen, and it really was a lifelong dream. I’m a bit old for Titania now, but I thought ‘Let’s go!’.

So when did Handel enter the picture?

It was through William Christie’s class that I met Christophe Rousset, and it was through Christophe that I came to Handel; I began to study with him too and he suggested me to sing Berenice in Scipione, which was my first Handel role. The director said ‘Sandrine is a specialist in eighteenth-century French music, it’s not possible!’, but Christophe fought my corner. My first solo recording with him came a little bit later, for Naïve, and it was in the same theatre in Poissy as Enchantresses - so things have come full circle!

I immediately had the feeling that Handel was just right for me, and somebody in the audience came to me afterwards and said ‘Tu as trouvé ta voix’ - in French ‘voix’ means both ‘voice’ and ‘way/direction/destiny’. Back then my voice sat pretty high, and the French repertoire is more suited to lower-voiced singers like Véronique [Gens] – these days it works for me too, but as a young singer Handel was a better fit. And finally I felt like a ‘Real Singer’, someone who can say ‘I will vocalise and ornament just for the beauty or the sheer physical pleasure of singing!’. But with Handel you get both: the characters are wonderful physically and vocally, and also very interesting psychologically and dramatically. So voilà, that was the beginning of my story!

Is there any repertoire which leaves you cold?

The only thing I can’t imagine ever doing is bel canto: 1) I don’t have the voice for it and 2) I don’t have the mentality for it, because the whole prima la voce thing terrifies me. It’s like singing Queen of the Night, when you know that the people are waiting for those high Fs – to me that’s closer to sport than music! For me it’s much more important to sing with other people and feel a connection: I know that does also happen in bel canto, but so much of it is about being out there alone with a big aria that relies solely on your voice and talent, and that’s not my thing. Alcina is a kind of bel canto, I suppose, but there are lots of other things going on there!

Have any particular stage-directors given you special insights into the women on the album?

Pierre Audi is my guiding light: he directed the very first production I did outside France (Monteverdi’s Poppea, in Amsterdam). When you meet these kinds of people when you’re young and fragile they can absolutely change your life, because you apply what you learn from them to every production you go on to do. Whenever I feel that a director has left me to my own devices, I imagine Pierre saying ‘OK Sandrine, don’t turn like that!’. There was a sort of choreography to everything he did, and sometimes it was complicated, yes – but it’s easier to feel natural on stage that way, rather than when you’re left alone to act natural and don’t know what to do with your hands!

Robert Carsen is fabulous in a completely different way – he has you running all over the place and always keeps you busy, but you’re never alone with him either! He has a thousand ideas for one scene. Those two are really very big inspirations for me. I also love Pierre Constant, who’s a very old man now – I did my very first Pamina with him and the late Jean-Claude Malgoire, and also my first Donna Anna, in Paris. Laurent Pelly is wonderful too; all his productions have very strong concepts. What I love about all these people is that they approach opera primarily as theatre, and they come prepared with clear ideas – I don’t like it when a director turns up and says ‘Let’s improvise!’. I’m sure that can be fabulous too, but personally I prefer to feel the work and the thought behind a production from the beginning.

Are there any major Handel roles left on your to-do list?

That’s difficult, because once you’ve sung Cleopatra or Alcina it feels as if you’ve already hit the jackpot: there aren’t many roles that match them for vocal beauty and drama, and where the interest is sustained through the entire opera. In Rinaldo for example, Almirena’s ‘Lascia ch’io pianga’ is fantastic, but the role as a whole is less interesting,

I can’t say that I dream of this or that, because I’m not somebody who maps things out: hell, I never even planned to be a singer in the first place! One thing I will never sing now (and this breaks my heart because I love Strauss so much) is Sophie in Rosenkavalier; the two productions I was supposed to do were cancelled, and now I’m too old for it. I think I’m a typical woman in that I exist also for the eyes of the people in front of me, and I know I’d look ridiculous - and sadly I’m not right for the Marschallin either.

But the recording-studio is a different environment, a dream-world of its own in a way. On a recording you can do things you’ll never be able to do on stage because of the distance or the acoustics: on Clair-Obscur I had the great pleasure of singing Strauss’s Vier letzte Lieder, and OK I’m not Renée Fleming, but I think it worked. Sometimes people say ‘Oh, you shouldn’t record things that you aren’t able to sing on stage because it’s not the truth’ - but what IS the truth anyway?! Not so long ago you saw opera from a distance, and it’s only recently that we’ve had cameras in our faces; these days you can’t sing a young woman when you’re old even if your voice is still young and you’re agile, but that wasn’t always the case. Now we have this fixation on hyper-reality, but that’s just as much of an illusion as what’s gone before: a horrible selfie taken on your iPhone isn’t you, and a wonderful photograph taken in the studio isn’t you either! Life exists in-between.

Speaking of photos, where was that stunning cover-image shot?

This was so funny – it was taken in the Bois de Vicennes in Paris, and because we needed to shoot it just before the sun went down there were joggers running past while I was getting changed! The dress was made by a friend from the Conservatoire de Paris, a singer who also studied costume-design, so it wasn’t expensive at all. I asked for something warm and heavy, covering the arms, but not the usual concert-black; he came up with this old gold that seems a little bit green here because of the light in the wood.

The photographer was Sandrine Expilly, who also took the photograph for Clair-Obscur earlier that same day: I always ask her to shoot my covers if she’s free because she absolutely understands the concept and ambience of every album. Alcina is the central role on Enchantresses, and the photo really captures this image of her bois enchanté where people are enticed and become unable to leave.

Sandrine Piau (soprano), Les Paladins, Jérôme Correas

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Sandrine Piau (soprano), Les Talens Lyriques, Christophe Rousset

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC

Sandrine Piau (soprano), Orchestre Victor Hugo Franche-Comté, Jean-François Verdier

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC