Interview,

Elizabeth Llewellyn on Heart and Hereafter

One of the stand-out new releases from May for me was British soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn's remarkable debut album Heart and Hereafter, which features a whole host of world premiere recordings of songs by the Anglo-African composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912) and includes some particularly striking settings of poems by Radclyffe Hall and Christina Rossetti. It was a great pleasure to speak to Elizabeth (who's currently preparing to sing Alice Ford in Falstaff at the Edinburgh Festival) about the process of discovering and selecting the repertoire for the album, the reception-history of Coleridge-Taylor's music, his affinity with texts written by women, and her personal favourites from this rich, diverse programme...

One of the stand-out new releases from May for me was British soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn's remarkable debut album Heart and Hereafter, which features a whole host of world premiere recordings of songs by the Anglo-African composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912) and includes some particularly striking settings of poems by Radclyffe Hall and Christina Rossetti. It was a great pleasure to speak to Elizabeth (who's currently preparing to sing Alice Ford in Falstaff at the Edinburgh Festival) about the process of discovering and selecting the repertoire for the album, the reception-history of Coleridge-Taylor's music, his affinity with texts written by women, and her personal favourites from this rich, diverse programme...

What sparked your interest in Coleridge-Taylor’s songs?

The seed was planted in 2013, when I was asked to jump in for Radio 3’s Schubertiade in lieu of a colleague who’d been invited to sing the Marschallin on the continent. There was just the slight obstacle that I didn’t actually know any Schubert…so I got in touch with Simon [Lepper] and said ’You’re going to have to give me an idiot’s guide to singing this music, QUICKLY!’. He very kindly coached me on the lieder I’d been asked to sing, and at the end of that session he showed me some songs of Coleridge-Taylor which he had on the piano and said ‘Have you heard of this guy? We really must bash through some of these’. That came at a very busy time in my career – everything kind of snowballed, but as I wasn’t being asked to do recitals it wasn’t really on my radar to do anything about it. Then in around 2017 I was doing some research on possible song-repertoire and thinking about putting them in a historical context, and on the back of that I called Simon up and said I thought a Coleridge-Taylor project had legs – there was enough material not only for an album, but perhaps even for a double-album! Then we gave our Wigmore recital last year, so it’s been a long time coming!

It’ll be interesting to see how people receive this album, because you could argue that I’m not a recitalist: the Wigmore concert was only my second professional recital, so I just had to take what I’d learned as an opera-singer and apply it to these songs. I learned to scale down what I was doing to suit the medium of song – but that said, you’ve still got to sing with your own instrument and voice, and everything that you bring to the table as an artist.

How did you go about tracking down the material?

It essentially involved whole days in the British Library, taking out ten tomes at a time and spotting poets that attracted me or things I particularly liked in the piano-parts, then going to the scanner and emailing them to myself! It’s really exciting – you feel as though you’re digging up buried treasure, and I couldn’t wait to get home to sit at a piano and see what they sounded like under the hand. There’s more detail on the discovery-process in this episode of my video-series.

Were any of the songs written with specific performers in mind?

There are various dedications, either to his wife or friends or children of friends, but as far as I’m aware none of them were written for specific singers. The one exception is ‘The King of Thule’, which was written as incidental music for Goethe’s Faust at Her Majesty’s Theatre and was performed by Marie Löhr, the very famous actress who was playing Marguerite.

How much information is out there about the performance- and reception-history of the songs?

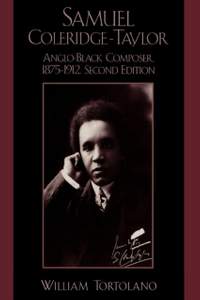

It’s all a little bit patchy, although I’m currently reading a biography by William Tortolano which goes into more detail. We know that Coleridge-Taylor made a few trips to the States: the performances there were mainly of his larger-scale works, but on one occasion they couldn’t get their ducks in a row so he put on a programme of some of his songs and smaller chamber works at the Mendelssohn Hall. Wigmore Hall recently invited me to look into curating a series of Coleridge-Taylor recitals, and I’d love to recreate that concert from November 1906: it included two singers (a baritone and a soprano), some piano transcriptions of the Negro spirituals that he’s famous for, and some of his works for violin and piano too.

It seems that during his lifetime people generally tended to prefer his larger works: obviously he was more famous for things like Song of Hiawatha, The Death of Minnehaha and the Violin Concerto, but the reason I wanted to do this album was that there are some real gems among his smaller-scale pieces. And his song-writing was well-appreciated - if not necessarily by critics (because they weren’t often performed), then certainly by performers. In the 1930s he was clearly a composer that singers liked to include in their recital-programmes: we’re talking about singers like Webster Booth and Dorothy Maynor, and in the 1980s Stuart Burrows. Some of the very scant recordings I’ve found on YouTube are from these singers: they’re sung in quite an old-fashioned way, but also very beautifully, responding sensitively to the text and not over-gilding the lily.

Even though I haven’t seen anything written down in correspondence or reviews, he clearly had an affinity with setting poetry written by women – Christina Rossetti features heavily on the album, and there are three songs on texts by Marguerite Radclyffe-Hall. He just seems to get it right somehow, which I find really interesting. Something that didn’t make the cut but which I would really love to hear (perhaps as part of that Wigmore series) is a group of songs for mezzo, or really contralto – they’re quite low, which is why they didn’t make it onto the disc! The collection’s called The Soul’s Expression, on texts by Elizabeth Barrett-Browning: I’m desperate to see if I can get a really excellent mezzo to perform them somewhere.

How much of a role do folk influences play in Coleridge-Taylor’s songs and wider output?

One of my guests on the video series is Charles Elford, the author of a book called Black Mahler: The Story of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. That ‘Black Mahler’ tag came out of a New York Times review in 1910, and having discussed this with Simon I think it came about because he was intent on using spirituals and folk traditions - not just in his vocal writing but in his orchestral music too. I suspect part of that was because he never knew his father’s side of his family, and I’m sure that’s what precipitated him going to the States and meeting up with Black musicians and poets and abolitionists: there was this natural desire to find out more about that side of his heritage, which he wrote about quite eloquently in letters and articles.

And it wasn’t just African spirituals that spoke to him: he seemed to be interested in anything 'other', as we see in the Native Indian elements of Hiawatha, and some of the solo songs that didn’t make it onto the album. There’s definitely a fusion going on between the European tradition and music of Native Indian or African heritage. Various composers were doing a similar thing at the time, and Coleridge-Taylor was a huge fan of Dvořák, who loved the idea of the music of ordinary working-class people being incorporated into mainstream classical forms.

To what extent was Coleridge-Taylor’s career hampered by racial prejudice?

Whether he wrote about it or other people did, it was definitely there: this is Victorian Britain we’re talking about. I was saying to my brother only the other day that we’ve got to remember that this was the era where Queen Victoria was ‘gifted’ a six-year-old girl [Sara Forbes Bonetta] who’d been rescued from West Africa; she ended up being Queen Victoria’s goddaughter, which gave her a very comfortable life and the freedom to marry the person that she wanted, but there’s no getting away from the fact that she was given as a gift in the first instance. And that context makes Coleridge-Taylor’s life and career even more remarkable: his composition teacher Stanford stood up for him because he was being ridiculed at the Royal College of Music, and Stanford went on record saying he had more talent in his little finger than some of the people who were mocking him. It’s inevitable that anyone who didn’t look European was going to have a tough time, and sadly that’s still a reality for people of colour in Britain and all over the world.

Did Coleridge-Taylor go on to teach much himself?

He did all sorts of jobs alongside composing, including teaching, adjudicating, and working as a conductor for choral societies. Like most of us (especially over the past year!) he couldn’t just rely on inspiration to earn a living: in fact he had to sell the rights to Song of Hiawatha to make money and support his wife and family. The scandal around that was actually the basis of reforming the copyright laws around publishing, because it showed up how unjust it was that composers could be duped out of something that went on to be really successful.

Can I pin you down to two or three favourites from the album?

Some which almost didn’t make the cut have ended up being favourites of Simon and mine. I mentioned Christina Rossetti earlier, and one of the first songs that springs to mind is Lament, on a poem of hers that’s been set by various composers: ‘Why did you die when the corn was growing?’. It’s so poignant – it’s not over-stated, and he doesn’t overstay his welcome. Even listening back on the first edit that was one of the tracks that really got me.

I’d also pick out ‘Tears’, from the set Southern Love Songs, for exactly the same reason: it’s so still and just kind of hovers, and it’s beautifully set in the voice as well. As a soprano who sings certain sorts of repertoire, I’m aware that if I go above certain notes it’s quite hard to preserve that almost cupo sound around it, and Coleridge-Taylor just seems to get that: he keeps it in a sort of bubble, never pushing higher than a G flat. It’s that very quiet and abandoned world of a young girl who’s only just given up hope that her lover’s going to come and get her, and it’s dawn and he’s nowhere and it’s all over. And everybody loves Big Lady Moon: there’s something of the music-hall about it, and it’s just very cute, disarming and charming. He does charm very well without overegging the pudding.

I remember listening back to an early edit of one track that was quite hard to pull off, and thinking ‘Yes, we nailed it!’: that was one of the Radclyffe-Hall songs, Thou art risen, my beloved. Coleridge-Taylor isn’t immune to that slightly Gothic Victoriana vibe that we sometimes hear in Elgar, and there’s something quite corset-busting about it: it’s rather a racy song when you look at the words, and there’s a lot happening underneath the surface! The piano-part’s always heaving and moving, so there’s that breathlessness of a secret rendez-vous between lovers who should not have been meeting. We think about the Victorians as being quite tight-laced and a bit bland and boring, but this is so exciting and sensual and I’m delighted that that came out so well.

Do you think the tide’s turning in terms of Coleridge-Taylor’s popularity?

I hope so. Debut albums are often meant to showcase a singer, but this really isn’t about me: it’s about how great these songs are! I hope it proves a useful resource for people, and that we get to a point where if someone’s planning a recital of English song it becomes as natural to programme Coleridge-Taylor as it is to programme Finzi or Vaughan Williams.

A lot of his music still hasn’t seen the light of day. There was a Surrey Opera production of Thelma in 2012, and Welsh National Opera recorded Song of Hiawatha with Bryn Terfel, but none of his other large-scale vocal works have made it that far…it would be lovely to see Thelma recorded, and performed at a major festival.

Elizabeth Llewellyn (soprano), Simon Lepper (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

William Tortolano

Available Format: Book

Helen Field (soprano), Arthur Davies (tenor), Bryn Terfel (baritone); Welsh National Opera, Kenneth Alwyn

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC