Interview,

Mark Simpson on Mozart and 'Geysir'

Since bursting onto the musical scene in 2006, when he became the first person ever to win both BBC Young Musician of the Year as a clarinettist and BBC Proms/Guardian Young Composer of the Year, Mark Simpson has continued to weave a dual career combining performance and composition.

Since bursting onto the musical scene in 2006, when he became the first person ever to win both BBC Young Musician of the Year as a clarinettist and BBC Proms/Guardian Young Composer of the Year, Mark Simpson has continued to weave a dual career combining performance and composition.

His work Geysir, commissioned for the Britten Sinfonia in 2014, is scored for the same forces as Mozart's Gran Partita (with which it makes up a new release on Orchid Classics, out on 20th November 2020) – a twelve-piece band of reed instruments and horns, underpinned by double bass. Simpson draws on his own experience as a wind player, and indeed of playing and leading the Gran Partita itself, to create a work that echoes the rich textures of Mozart's while at the same time expanding its sonic palette.

Geysir is a fascinating work – immediately accessible and yet also concealing hidden depths. It combines a taste for piquant orchestrations with a pointillistic approach to melody, with fragments exchanged throughout the ensemble. I spoke to Mark about how this piece took form, and the relationship it has to Mozart's Partita.

The title of this piece refers, of course, to the iconic and awe-inspiring hydrothermal phenomenon seen in Iceland, Wyoming and elsewhere. It’s a vivid and inspiring image to draw on – but how did you first settle on this as the theme of the work?

Like any new piece, the gestation period is often filled with many false starts. The original idea for the piece was to have the ensemble placed in a semicircle and divide it into two wind sextets (oboe, clarinet, basset horn, bassoon, two horns) with double bass in the middle, reflecting each other, mirror-like. This mirror-like concept forced me to explore the possibility of palindromic material. However I got nowhere with this avenue of enquiry. I went back to the Mozart and simply listened to the sound of the ensemble again with that glorious B-flat major chord that opens the piece. I reconnected myself with the feeling of breath and tried to develop something that had a physical, bodily connection to the sound. (The physicality of music is very important to me as a performer/composer. When I write it has to feel as if it emanates from body in some way.)

After I felt like I had connected with the sound of the ensemble again I was able feel my way through the piece and let it take its course. As always, this is done between piano and paper at the desk. At the end it turned out to be this melting pot of swirling colour with a powerful forward moving energy. Once I had finished the piece, I showed it to the dedicatee, the composer Simon Holt, who remarked that the musical structure, with its relentless build up of energy and subsequent explosion very much resembled that of a geyser. This struck me. He was right, and I quite liked that visual imagery. So the title and imagery came after the piece was written. I think people have this notion that ideas/imagery/concepts for pieces exist as a solid framework before a note is written and everything flows naturally from that source. In my experience this is never the case. The ambiguity, the ‘not knowing’ is part of the process.

The wind textures Mozart uses in the Gran Partita have clearly had an impact on the construction of Geysir; who would you say were the main influences on your compositional style in a broader sense?

My earliest and most formative musical influences were Thomas Adès, Mark Anthony Turnage, George Benjamin, Julian Anderson and Simon Holt. In that respect I would say that I would sit firmly in an ‘English’ tradition. My music does sound ‘English’ when it’s performed abroad. It may have an American flavour to it too. John Adams was a big influence too. They’re all in there I think.

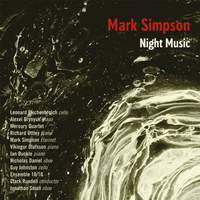

Around the release of your album of chamber music on NMC, Night Music, my colleague James wondered whether your twin roles as clarinettist and composer might weave together into the form of a clarinet concerto; is this something that’s still on the cards, or do you prefer these larger, more “textural” ensemble works?

I actually wrote a clarinet concerto last year and it’s up for the large scale orchestral award in the Ivor Novellos this year! I’m in a string of concertos at the moment, having written a cello, clarinet, and currently working on a violin concerto. I was working on one for electric guitar concerto too but that was postponed due to the Covid crisis.

You mention wanting to give the horns a bit more prominence in Geysir, since they are quite self-effacing in the Gran Partita. But Mozart was no stranger to writing idiomatically and soloistically for the horn, as his four concerti and chamber music attest. Why do you think he didn’t give the horn players in the Partita so much to do?

Interesting question. I think probably because of the nature of the melodic writing. There’s no way he could have had the fluency or continuity that he achieved if the horns were front and centre. He was probably aware of the difficulty of playing for extended periods of time too. He was also probably thinking of the wind soloists who would have performed for him – Anton Stadler, the famous clarinettist he wrote the concerto and quintet for, for instance. The first known performance of the piece was at a benefit concert for him.

The Gran Partita may have evolved out of commodified “light music” to be played in the background for social events, but so arguably did the string quartet – today considered a prestigious musical genre. Why do you think the fate of the wind band was so different?

The homogeneity of the sound. The sounds just don’t blend as well as a family of string instruments. Considering how many different clarinets were being developed during that time and after, I’m surprised the clarinet quartet didn’t take off! But strings have a lot more flexibility and the wind instruments were cumbersome and yet to be fully codified.

Geysir may be a representative of the long and noble tradition of commissions seeking to create companion-pieces that share the orchestration of an existing one, but it’s clearly much more than that – and the sonic possibilities of that thirteen-player ensemble are enticing. Do you see yourself writing more works for these forces in the future?

When I was revisiting the piece for the recording I did wonder if it should have a few more movements representing other natural phenomena perhaps? But I think it does stand on it’s own too. You need to consider the effect of playing a full concert on the lips of the wind players. The Mozart alone is a mammoth blow. You always get to the last movement and think ‘Oh god, we have to play this now.’ having played continuously for 50 minutes. So this piece is designed to open a concert in the first half, with something lighter after it, with Mozart following after the interval. Maybe in the future I might add a few others, but not now.

Mark Simpson, Fraser Langton (clarinet), Nicholas Daniel, Emma Fielding (oboe), Amy Harman, Dom Tyler (bassoon), Olver Pashley, Ausias Garrigos Morant (basset horns), Ben Goldscheider, Angela Barnes, James Pillai, Fabian van de Geest (horn), David Stark (double bass)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Leonard Elschenbroich (cello), Alexei Grynyuk (piano), Richard Uttley (piano), Mark Simpson (clarinet), Ian Buckle (piano), Víkingur Ólafsson (piano), Nicholas Daniel (oboe), Guy Johnston (cello), Jonathan Small (oboe), Mercury Quartet

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC