Interview,

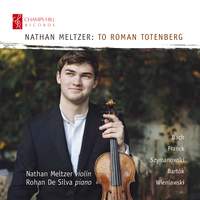

Nathan Meltzer on Roman Totenberg and a lost-and-found violin

Young US violinist Nathan Meltzer bursts onto the recording scene with an original and absorbing recital – tracing the music that was once performed on the violin he now plays, the 'Ames Totenberg' Stradivarius. As Meltzer explains, it's an instrument with a dramatic history of its own, having been stolen by a jealous fellow-violinist and been thought lost for decades. It also forms a unique link across the years between a rising violinist of the 2020s and a performer and educator of a wholly different era – a musician born in 1911, who played for the Roosevelts and performed with Rubinstein and Szymanowski.

Young US violinist Nathan Meltzer bursts onto the recording scene with an original and absorbing recital – tracing the music that was once performed on the violin he now plays, the 'Ames Totenberg' Stradivarius. As Meltzer explains, it's an instrument with a dramatic history of its own, having been stolen by a jealous fellow-violinist and been thought lost for decades. It also forms a unique link across the years between a rising violinist of the 2020s and a performer and educator of a wholly different era – a musician born in 1911, who played for the Roosevelts and performed with Rubinstein and Szymanowski.

Meltzer talks about his relationship with this instrument, and about his personal mission to broaden the listening palate of classical music fans through his Opus Illuminate initiative - an online concert series dedicated to the chamber music of composers from historically underrepresented communities.

This is a remarkable debut recital-album, revisiting some of Roman Totenberg’s repertoire on his own rediscovered instrument. Can you tell us a little about how this project first came about?

The opportunity to record my first CD was made possible by the Windsor Festival, whose International String Competition I won back in 2017. Along with a performance with the Philharmonia Orchestra, the prize included a recording session at Champs Hill Records. When I had the great fortune of being loaned this incredible violin, and after learning about its remarkable history and Roman Totenberg, I knew what I wanted to pay tribute to with this album.

Totenberg’s Stradivarius was lost for nearly four decades after being stolen from the Longy School of Music; the notes accompanying this album even refer to it having passed through the FBI’s hands at some point. How was it eventually recovered – and what made it such a unique and valuable instrument to take?

The story of the violin is both tragic and fascinating. Four decades after its theft, and unfortunately three years after Professor Totenberg’s death, the thief’s ex-wife discovered the violin with its 'Antonio Stradivari' label. She soon met in New York with an appraiser – and the FBI and the US Attorney. The instrument was returned to the Totenberg family, who wanted to honour their father’s memory by keeping it in the hands of an aspiring musician. Enter the wonderful people at Rare Violins of New York, who restored the violin and loaned it out through their 'In Consortium' program, which provides fine violins to performers with the support of generous benefactors.

Totenberg himself recorded several of the pieces you’re performing here – the Bartók Rhapsody and the Franck Sonata. Did you try to immerse yourself in his own archive performances when preparing this recital?

It was a tricky balance to strike. Of course, the album is an homage to Professor Totenberg, and thus I wanted to have elements of his musical sensibilities included in the recording. However, as any good teacher makes clear - and Professor Totenberg was a great teacher - the goal of teaching is not to create clones of your own playing. I took much inspiration from listening to Professor Totenberg’s recordings, but I was never trying to emulate his playing. Rather, I believe that the truest form in which I could have paid my respects was by applying my own artistic sensibilities to the works that Professor Totenberg championed.

You demonstrate a clear affinity for this kind of Romantic repertoire, especially in the Wieniawski Polonaise; is this period one that you’ve particularly focused on during your time at the Juilliard School?

Romantic-era repertoire was the first style of music that I fell in love with; over time, I’ve come to adore other styles of music just as much. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve learned to venerate music of the Classical and Baroque eras. And especially since my partner is a composer, I’ve become immersed in the world of contemporary music and am now incredibly fascinated by that musical language.

Your approach to the Bach Sonata is one that violinists of Totenberg’s heyday would probably recognise – unashamedly 'inauthentic' to modern ears. Do you think we’re now at a point where revisiting early twentieth-century takes on early music is now, itself, part of the world of historically-informed performance?

It’s a testament to the strength of the music of Bach that it’s able to be interpreted in so many drastically different ways. I equally love both Grumiaux’s and Rachel Podger’s Bach recordings, despite their almost polar-opposite approaches. As artists, our sensibilities are almost entirely subconsciously crafted from our surrounding influences. I’ve always found it difficult to impose a style onto my interpretation. All I can do is play the music in the way that it speaks to me, which I guess is heavily influenced by twentieth-century performances. But again that’s never something I’ve consciously considered trying to emulate.

Since the 'Homecoming' concert you gave in late 2019, the world has of course changed in profound ways, including for musical performers and students. How have your studies at Juilliard, and your music making in general, changed as a result of the unprecedented situation in which we find ourselves?

As with almost every performing artist around the globe, the pandemic left me with a lot of time to think and reflect upon what it means to be a musician. The arts have the potential for amazing and powerful influences on society, for preserving the virtues of our era and also exposing the flaws. This is an aspect of the concert-going experience of classical music that gets mostly overlooked, by myself included. Music typically programmed, while filled with genuine masterpieces, is comprised of pieces written by a limited demographic. By continuing this practice, I believe classical music will suffer. I believe by diversifying the cultural heritages of the composers whose music we play, we expand and beautify the range of what classical music can offer. And so now, where the performance of classical music has been forced out of concert halls, is a perfect time for us to expand the boundaries of what we perform.

After such a bold and original debut, can you tell us anything about your future recording plans – once circumstances permit?

Through the founding and directing of Opus Illuminate, I’ve learned so much about a whole new repertoire that, in many cases, has gone sadly unnoticed. If I have the good fortune to make another album, I will definitely be interested in making recordings, in some cases the first ever, of some of these works!

Nathan Meltzer (violin), Rohan de Silva (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC