Interview,

Robin Ticciati on Strauss

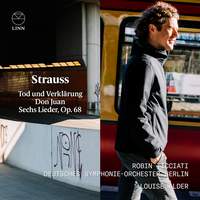

Since we first met up to discuss his Brahms cycle with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra in early 2018, I’ve enjoyed several candid and insightful conversations with the young British conductor Robin Ticciati, and the release of Strauss’s Tod und Verklärung, Don Juan, and Brentano-Lieder with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin (his sixth recording with the orchestra) earlier this month seemed a prime opportunity to renew the acquaintance.

Since we first met up to discuss his Brahms cycle with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra in early 2018, I’ve enjoyed several candid and insightful conversations with the young British conductor Robin Ticciati, and the release of Strauss’s Tod und Verklärung, Don Juan, and Brentano-Lieder with the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin (his sixth recording with the orchestra) earlier this month seemed a prime opportunity to renew the acquaintance.

We spoke a few weeks ago about the connections between the three works on the album, the orchestra’s ongoing relationship with this repertoire, how his own personal perspective on music-making has shifted in lockdown, and how that informed his approach to programming some recent open-air concerts at Glyndebourne…

Has your perspective on these works undergone any kind of ‘transfiguration’ of its own over these last few strange months?

Some of the editing for this recording actually took place during lockdown, which I found rather beautiful: it’s one thing to record a piece like Tod und Verklärung in normal conditions, but revisiting it in this context made me immensely thankful for the orchestra that I’m responsible for and reminded me just what an extraordinary thing it is that they do. When I listened I was transported back to Jesus-Kirche in Berlin: that long lingering first note from the bassoon is like a thread of life, and it prompted me to think a little more about the individual people who were making these extraordinary sounds. I wouldn’t go as far as to say that the idea of facing death itself (in a way that one would in the meditative sense) has changed much for me at the moment when I do that piece. That would take a lot longer – probably a lifetime! I still think I relate to this music on a very artistic, Romantic level.

This is the thing about Strauss: I love it and I’m beguiled by it, and I’m moved and I weep, but he’s a master-manipulator, and I am very happy to be manipulated! I don’t get drawn into the beauty of Death; I get drawn into the extase of the Transfiguration. I keep on wanting Tod und Verklärung to have been written later than Don Juan, but they are actually incredibly close in terms of composition-dates, and I think that maybe goes back to this idea of Strauss as master-craftsman: he’s a chameleon, and such a prolific writer of notes that can lead your heart down a certain alley-way. That’s not to discredit it - it’s totally genuine, but it’s also about sheer proficiency.

Speaking of proliferations of notes, I was struck by how much stillness you find in Don Juan – was that something you consciously tried to cultivate?

Yes, and I’m thrilled that came across for you on the recording! There are so many moments of stasis and reflection in Don Juan: of course it’s full of paraphernalia and fireworks, but there’s a plaintive, still-beating heart at the middle of that work. It’s not really anything to do with love or seduction - it’s about the protagonist’s profound internal sense of loss and loneliness, rather like the canzonetta in Don Giovanni. We performed the piece a lot at home and on tour, and I loved that it was always the same oboist; I feel there’s a deep sadness in that oboe solo, and I hope we managed to create the space to convey that without dismembering the line.

What was the thinking behind coupling the Brentano-Lieder with these much earlier pieces?

There’s the obvious connection of all three works confronting ideas about love and death: Strauss of course would refer back to Tod und Verklärung from the perspective of an old man on his death-bed in the Four Last Songs, so in a sense there’s a natural book-end. But the main reason was simply that I love inviting a soloist onto an orchestral disc, whether that be a singer or an instrumentalist. I know most people listen to music through download or streaming services these days, but rightly or wrongly I still think in terms of discs because that’s the world I grew up in, and so I like to have some sort of juxtaposition on my recordings. It’s also nice to have a relative rarity on a disc, and that’s really where the Brentano songs came in – they don’t often get an airing because they’re so fiendish to sing! You need a Zerbinetta, a Sophie and a Marschallin all in one voice: even though it was written for Elisabeth Schumann, an incredible coloratura (as evident in the pyrotechnics needed for Amor!), the outer ones are pretty big sings, so you don’t often find sopranos that want to do the whole set in concert.

The fact that he went back to reorchestrate these songs at the end of his life says something about how he felt about them: five of the six orchestrations date from 1940, so around the time of Capriccio and Metamorphosen, and not so very long before the Four Last Songs. The orchestration is not in any way showy: the solo cello, horn and oboe are always cantilena around the voice, and he saves the heavies – the trombones, tuba and bass drum - for the last song. But they feel like incredibly honest expressions of the text: they don’t have the grandeur of the Four Last Songs, but there’s something just as special about them.

When we’ve spoken before you’ve mentioned that you generally avoid listening to others’ interpretations of works you’re preparing – but in a case like this where we have recordings of the composer himself conducting a piece, do you make an exception?

There’s a 1920s recording of Strauss conducting Don Juan and Tod und Verklärung with the Berlin Staatskapelle, and when there’s a document like that available of course you want to hear it; I’m fascinated more by what doesn’t happen than by what does with that recording. Did it affect my interpretation? If it did, it was subconsciously. It was wonderful to have heard it, and I think it goes back to that question of Strauss style, which is so affected by the development of the orchestral sound: the size of the instruments of that time, and how loud they were. But things have changed: if the oboe can do more things now in terms of sound or sostenuto or the variability of vibrato, that can work its way into a modern interpretation and have an effect on tempo structures and rubato. So I listened more as one would read a document – it didn’t necessarily touch me.

A few weeks ago I heard Iván Fischer give a wonderful interview to Kirill Gerstein about the state of the symphony orchestra. It was quite dark but revelatory, and he was just saying that with Strauss and Mahler the orchestra got to its peak – there are basically no more instruments you can fit on stage! So what is ‘Strauss style’? I think it’s so much about the character and temperament of an orchestra, and its relationship with a conductor. And that was a very exciting thing for me about this process: the DSOB doesn’t have a specific Strauss history, but there is this incredible lustre and excitement for performing these works. It’s always been an orchestra that’s very chameleon-like in its programming, but I felt that when we performed these works over the season and tour a real kinship with Strauss emerged, and that’s something that I’m really looking forward to developing.

What’s the next stage in that development?

In terms of recording, you know me well enough now to know that when I record I need to feel that I’ve got a piece really internalised, and that what I have to say is specific enough for it to be out there! I’m not so into Till Eulenspiegel or Symphonia Domestica yet, but in terms of concerts I’ve got Eine Alpensinfonie and Ein Heldenleben coming up, and of course we’ve asked Louise to come and sing these astonishing Brentano songs in concert.

When did you start working with Louise?

She stepped in for our 2014 Prom of Der Rosenkavalier when the Sophie fell ill, and was just extraordinary: Louise is one of those singers where her technical facility is so at ease that the musical expression is never, ever compromised. And as a conductor you feel that whenever you make a shape with your arms or an expression with your face she’s right there to react to that and play with it. I so love working with her; we did a concert with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe where she gave a portrait of Mozart’s women (Servilia, Susanna, Fiordiligi, Zerlina), and it was wonderful to hear that clarion, crystalline voice bring all of those characters alive. And the Brentano-Lieder are not so far away from that: the last one is a big sing, but I think she fits them all beautifully.

Music aside for a moment, how have you been spending your time in lockdown?

Like most people I found I wanted to read a lot more, so I revisited John Banville’s works, which I’ve loved for years and was eager to revisit in a new light. And I also got into Ben Macintyre’s spy books in an almost addictive way – I’d never been so interested in that world of espionage, but in a funny way I felt it was filling a gap in terms of the things music does to one’s adrenaline! But I think for me the biggest change is that I have really worked on cultivating stillness, and this feeling of not grasping for things: when you stop working, you have to ask yourself what drives you, what is it that makes you open a score.

Everyone’s gone through such different things over the past few months. About four years ago I had a back operation and couldn’t conduct, so I think I had done that bit of grieving already in a sense, and for me personally this was an opportunity to look inward and think about my relationship with music and other people’s relationship with music. It’s all part of a process, but it certainly started something off which I found very important in terms of rediscovering the pure joy of the notes resounding.

And I gather you've already had a chance to put some of that into practice with your recent socially-distanced performances in the UK?

Yes: that idea really underpinned the programme I put together for our outdoor concerts at Glyndebourne, which I called 'Reverberations in Nature'. We started with Gabrieli brass chorales over the lake, followed by the Siegfried-Idyll, and then went attacca into Ives’s The Unanswered Question, where we put the single trumpeter in the sheep-field! Then Karen Cargill sang some Mahler songs (ending with Urlicht, with its imagery of the rose and man lying in great pain), then into Takemitsu’s Signals from Heaven, where the brass-players went to the turrets of the opera house. It was the first live music in almost six months for some people, and I wanted to create 45 minutes of real buzz. In the second half there was a ridiculous but brilliant Offenbach operetta (Mesdames de la Halle), with a great translation from Stephen Plaice; we had a local cast, which included people like Kate Lindsay and Allan Clayton. I think it touched people, and that was the main purpose.

Now more than ever, we need to think about how we want to perform things, and in what spaces. I think this sudden drought of art (and this seemingly uncaring government’s response to it) has really underlined why it can be so life-giving for people, so now we have to work even harder to give music in a way that feels like it can be more of a support to people’s lives. It’s been a horrific time, and everyone comes from such a different place, but I think it will ask big questions of us as musicians and artists about how we go forward from here.

Louise Alder (soprano), Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Robin Ticciati

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC