Interview,

Kent Nagano on Penderecki's St Luke Passion

One of the most enduringly powerful works by the late Krzysztof Penderecki (who died at the end of March this year aged 86) is his St Luke Passion, a monumental work for enormous forces that manages to combine an unrepentantly modernist tonal language with a direct and humanistic emotional impact.

One of the most enduringly powerful works by the late Krzysztof Penderecki (who died at the end of March this year aged 86) is his St Luke Passion, a monumental work for enormous forces that manages to combine an unrepentantly modernist tonal language with a direct and humanistic emotional impact.

The composer himself was closely involved in a performance of the Passion at the 2018 Salzburg conducted by Kent Nagano and the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal - both of whom he had had a close relationship with over the years.

I spoke to Kent Nagano about this enormous project, and about his own personal connections to Penderecki and his music.

The Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, which you’ve conducted since the mid-2000s, had a unique relationship with Penderecki – indeed you yourself discussed the St Luke Passion with him in the past. Can you tell us a bit about how those relationships with the composer developed, and how they inform the way you approach conducting this work?

I was studying composition during the 1970s, and we were very much aware of his work; he would occasionally frequent the San Francisco area. During this time I heard performances of the pieces that since have become well-known and established in the repertoire. For composition students the 1960’s works including, Threnody, the Stabat Mater and the St Luke Passion, and later the Magnificat of the 1970’s which overlapped my student time, were considered important works. They represented one of the many ways of approaching the postwar aesthetic, and I knew his work well even though we didn’t have the chance to meet during those days.

It’s a bit of a coincidence that he and the OSM’s relationship began at about that same time – of course we (the OSM and I) did not know each other at that point. Both relationships have continued; I began with the orchestra in 2004 and have been with them for the ensuing sixteen years. Before and during my period, Penderecki came back regularly as guest conductor, conducting his own works, such that relationship was kept current and alive.

It was during one of those periods, in the early 2000s, that we had a chance to meet personally and reaffirm a former meeting, which was when I was invited to his wife Elżbieta’s Beethoven Festival in Poland. He very generously took the time to come and meet with me; we had dinner together. That’s when we became close personal friends.

This recording is live, taken from the opening concert of the 2018 Salzburg Festival; the Festival too seems to have had a special relationship with Penderecki, with an earlier Salzburg performance of the Passion, in 1969, coming to be seen as a symbol of reconciliation between Poles and Germans. Comparisons with Britten’s War Requiem suggest themselves; do you think there’s a similar spirit to the Passion?

My adolescence came in the late 1960s and early 70s, and from a social point of view I vividly remember it as a very turbulent time. It represented a major social movement, tied not only to what was happening in Czechoslovakia and Poland but also to the Vietnam War, which was nearing its peak which would come in the early 1970s. All of this was underpinned by a very strong feeling of transition, or at least instability within political structures – including, by the way, the lead up of what we now call the Watergate scandal. It was really moment in time when the performing arts and especially music were engaging themselves as as vital, pertinent forms of expression relevant to the evolving societal changes.

Whether or not there was a specific connection as you’re referring to I don’t know; I spoke at length with Mr Markus Hinterhäuser, director of the Salzburg Festival, and it was his idea to bring back the St Luke Passion after about half a century. That 1969 Salzburg performance was just a few years after it was premiered, which I believe was in 1966; it was still very much a new work at that time. When one goes back to this work decades later, it is fascinating to see that the fundamental themes which are dealt with through Penderecki’s musical language still remain as pertinent today as they were many decades ago.

The Passion is eighty minutes of almost entirely atonal music – a prospect many audiences, and indeed performers, might find daunting. What would you say to someone trying to “get into” the music for the first time – is that sense of constant disorientation the point, or are there musical elements you’d direct people towards latching onto to help decipher it?

Well, it’s true that many people, when they hear the word “atonal”, have almost a reflex response. But of course we’re surrounded in nature by atonality. What I would say to a first-time listener is maybe just for the moment forget about the terminology “atonal”. The work has very tonal anchors – major and minor chords anchor the piece, and these anchors clearly mark certain structural moments. It’s like a roadmap assuring us that we’re headed in the right direction even though we may never have been there before. Just having that roadmap of these anchors, I can in some way offer a sense of comfort and confidence.

I would also say that Penderecki’s way of employing certain compositional gestures also elicits very familiar humanistic reference points that we experience and live with on a daily basis. These are expressed in such pure forms that they seem to transcend questions of harmonic structure. Everything feels very humanistic. This series of tableaux that we’re taken through in the St Luke Passion never leaves us alone, lost and adrift in alienness. We’re surrounded by familiarity, and I think that’s what makes the piece so very special and why it continues to be programmed today when many of the pieces that that epoch produced have not survived into the twentieth century. The St Luke Passion stands out because it is, at its foundation, very human.

In your 2018 interview speaking with Penderecki and Benjamin Schwartz, you alluded to the OSM having a uniquely European sound among North American orchestras, due to Quebec’s particularly European culture. Do you think this affinity comes into play when the OSM performs works – particularly new ones – from Europe?

It’s always dangerous of course to make generalisations – it would really depend on the composer. If you take any three composers, no matter what their nationalities or background, their personal cultural heritage can be very different, so generalizing Quebec may give wrong impressions. What I was referring to in that interview was that Quebec is a very unique part of North America. North America is generally considered the “New World”, at least from the historical perspective, but Quebec is the one part of the North American continent that has never had a real intentional rupture, or revolution against its European heritage. Rather, that line is felt as an uninterrupted series of cultural developments - one senses Quebec has retained certain European sensibilities. You feel it obviously in the many languages that are spoken in Quebec – not only are we bilingual but many can speak Italian, German, Spanish – these languages are very active and they help make a special cultural mosaic there.

Musicologists say that language does have a very clear influence upon how you phrase, articulate and how you socially carry yourself, and these many European languages active in Quebec form a very rich texture. That’s what I was referring to in the interview, and that’s what makes Montreal fascinating. Clearly many of the stereotypical New World dynamics are there – openmindedness, invention, curiosity, technical facility, ultra-precision and the ability to move quickly and flexibly. These are all things that we think of when we think of the New World, and very much alive in Quebec as well.

It’s the coexistence of both which I think makes the OSM so unique. It allows a particular dynamic in our music making and is born out of the characteristics of this unusual corner in the world – a carrefour, if you will – a historical and actual crossroads in North American history. There are times when we’re rehearsing the orchestra and I can ask for particular colours, particular shadows, tableaux, historical references that the orchestra draws from its cultural heritage. One feels an instant empathy with the beaux arts.

I feel that in the case of Penderecki, it’s even more enhanced because the orchestra and Penderecki have had – completely separately from me – this five-decade-long relationship. You surely get to know someone over five decades!

Musical parallels with Bach’s Passion settings are inevitably drawn when discussing Penderecki’s St Luke Passion; how much do you think these are projected onto the piece by audiences and critics, and how much was Penderecki genuinely setting out to write a successor work to those of Bach?

It’s an interesting question. I can say that one of the main advantages of working with a living composer is if one is not sure of what the composer’s intention is, you can ask the composer. It was very special that Penderecki and I were able to spend so much time preparing for this performance of the St Luke Passion – I had performed it before, but to do it this time under the guidance of Krzysztof was obviously much more special. We did speak about Bach, but rather than try to speak for Penderecki about his intentions, I can only say that he was extraordinary wise, yet full of humility, and many times he confirmed the importance of Bach as a composer – how much this meant for his own personal work and what an influence Bach had upon his ideas of music.

This is not to say that he set out to do a continuation of Bach’s work or saw himself as a successor; just from knowing him, I would think that his humility would never allow him to think of himself in those terms! But he did freely share his love for, and the influence of, Bach on his work.

Given the Passion’s profoundly religious subject matter and its composition at the height of the state-atheist Communist era in Poland, would you call it a sacred work, or more of a dramatic one – especially given the plans for the Salzburg performance where you considered placing the Evangelist in a pulpit-like structure on stage?

The distinction between the sacred and dramatic is a relevant one to draw I believe, in the sense that the Passion itself is of great relevance. In this case in Salzburg, though, the plans you’re referring to came about from a purely practical perspective. The orchestra is abnormally large, and of course there is a large chorus that’s made up of sub-choruses, which have to have a certain physical isolation from one another in order to understand the polyphony, so that requires even more space – plus there is the boy’s chorus. The amount of space that’s needed for this work makes it very challenging to fit onto a normal-sized stage. In addition, there are a number of vocal soloists who need to be very closely coordinated together with the orchestra, and one of the traditional positions of placing them could be to have them standing in front of the chorus behind the orchestra. This was not very practical for us because of the chamber-music-like moments where the soloists interact with the front players of the string section. In Salzburg we tried to bring the vocal soloists very close up to be near to the conductor and also next to the string principals for ensemble reasons.

So: Where do you put the Evangelist? It’s getting awfully crowded up there. So for purely practical reasons we thought about having the Evangelist elevated, towards the back of the orchestra but visually and physically raised so that the voice could carry above the orchestra and he would be a separate entity from the choir. In the end, in the Felsenreitschule, which is where the performance took place, from a physical and practical point of view it just didn’t work. Having the Evangelist at one side of the orchestra really severed the contact that the speaker would have had with a major portion of the hall.

As a result we improvised a solution – the arcades which are a historical part of the Felsenreitschule, and part of what brings such a special atmosphere to the performance venue. The archways up above presented a beautiful framework for the picture of this massive choir and orchestra. The centre arcade also proved to offer an extraordinary acoustical projection for the speaker, so the speaker was then placed exactly in the centre of the picture, elevated above the tutti, so that he could – in a theatrical or dramatic way – present himself as presiding over the “congregation” as he was telling his story.

So yes, there is a theatrical element to the work; there are very dramatic aspects. But that specific idea about positioning the speaker was more to do with what seemed to be the most practical way forward.

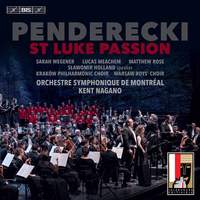

Sarah Wegener (soprano), Lucas Meachem (baritone), Matthew Rose (bass), Slawomir Holland (speaker), Krakow Philharmonic Choir, Warsaw Boys' Choir, Montreal Symphony Orchestra, Kent Nagano

Available Formats: SACD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC