Interview,

Lars Vogt on Brahms

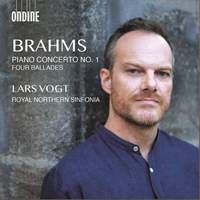

Since his appointment as Music Director in 2014, Royal Northern Sinfonia have certainly got their money’s worth from Lars Vogt – the German pianist and conductor has done double-duty as soloist and director on six recordings, including recent accounts of the two Brahms concertos on Ondine which BBC Music Magazine described as ‘sounding like large-scale chamber music’ and Gramophone praised as ‘nothing short of sensational’. We spoke last week about how his interest in conducting was kindled and developed alongside his playing career, his long-term relationship with Royal Northern Sinfonia, and the rewards and challenges of directing these particular works from the piano.

Since his appointment as Music Director in 2014, Royal Northern Sinfonia have certainly got their money’s worth from Lars Vogt – the German pianist and conductor has done double-duty as soloist and director on six recordings, including recent accounts of the two Brahms concertos on Ondine which BBC Music Magazine described as ‘sounding like large-scale chamber music’ and Gramophone praised as ‘nothing short of sensational’. We spoke last week about how his interest in conducting was kindled and developed alongside his playing career, his long-term relationship with Royal Northern Sinfonia, and the rewards and challenges of directing these particular works from the piano.

At what stage in your career did you become interested in conducting?

The interest’s been there for a long time, but the intention to actually pursue it came much later. It all began when I was around twenty and started working with really fantastic conductors like Simon Rattle, Christian Thielemann and Paavo Järvi, and at first it was just fascination: a conductor has the capacity to make a performance absolutely wonderful (or in other cases not so wonderful!), and I was always intrigued to see exactly what these guys at the top of their game did to make such a difference. At that point I didn’t really have any thoughts of entering the profession myself, but then after my US debut in Los Angeles in 1991 Simon and I were walking off-stage together and he suddenly turned to me and said ‘In ten years you’re going to be a conductor!’. It came as a shock to me, so I asked him what made him say that; he answered that he simply sensed I had a real interest in the whole picture rather than just my own part. And I guess that’s a view that came from my chamber music work: thinking about how I blend my piano sound with string instruments and winds, judging the importance of voicing and so on.

Did you take time out to study conducting formally, or was it a case of learning on the job?

A bit of both. I did take some technical lessons in my hometown of Düren, and my good friend Heinrich Schiff was also very supportive - when I got my first gig with a professional orchestra I remember going to see Heinrich for some pointers, and because so many of my friends are conductors I’ll often ask them how they go about certain things. And I do still work quite regularly with a conducting coach, Mark Stringer in Vienna, who is an absolute mine of information and the most wonderful teacher.

Of course I also learn a lot from observing the conductors I work with as a soloist, and also through videos of performances and rehearsals – Paavo and Christian especially are so instructive to watch on film. I’ve performed the Brahms D minor concerto with both of them and with Simon: Christian’s definitely influenced me in terms of the way that he shows colours and lines and gives the orchestra freedom, but really you get something from everyone! It’s a little like listening to recordings of other pianists – there will be certain bits that I like and think ‘Ooh, perhaps I could steal that!’ and identifying the bits you don’t like so much is also really helpful in refining your thinking!

What sort of precedent is there for directing the Brahms concertos from the piano?

Hans von Bülow used to do it with the D minor concerto, so the practice goes back quite a long way; I was actually quite surprised to learn that he did that one rather than No. 2, as I find No. 2 is a bit more straightforward in terms of play-conducting. It doesn’t have quite as much rubato, whereas No. 1 has so much in the first movement, and that’s something where you need a lot of trust between the soloist and orchestra, as well as a concert-master who really is in the same boat as you. With Royal Northern Sinfonia my concert-master was my great friend Bradley Creswick, whom I absolutely adore: Bradley’s a legend for a reason, and he’s been a shining example to me of how to be an artist. He’s just so open and unprejudiced and positive, and he brings such huge amounts of motivation and fun to every single rehearsal. As play-conducting pieces go, the Brahms concertos are quite advanced, and having that close rapport with my leader was such a major factor in making it all work.

What are the trickiest corners to manage, and how much direction are you able to give during passages when you’re playing?

Getting to conduct those big tuttis where the piano is tacet is such a joy – the first tutti of No. 1 and the one after the first cadenza in No. 2 in particular. Having lived with these pieces for so long, I’d developed such detailed ideas about what I would do with them – where I would like to take time, where I would like to press forward and so on, so finally being able to realise all of that was the most wonderful thing. But the orchestral passages where I’m completely busy on the piano and everybody’s playing flat-out are a bit more of a challenge…There’s one corner towards the end of the first movement of No. 2 where there’s a tricky descending passage in the right hand which becomes softer and softer as it moves down and then the orchestra have to come in with these three chords – that’s incredibly hard to do like this, because the concert-master is the only person who can cue it and the horns and trumpets have to be right with the pizzicato of the strings. Bradley did a fantastic job, but it really takes anticipating from the wind-players and needs a lot of rehearsing. There’s another sticky corner towards the end of the first movement where things phase out a little, and usually people do a little bit of ritardando - but just how much do you do, and where exactly do you start it? I have my hands completely full playing, but I found it’s essentially like chamber music: you have to find ways of communicating with the body, right down to the eyebrows!

How did your relationship with Royal Northern Sinfonia begin?

As a soloist I’ve had a relationship with the orchestra for a while – now I come to think of it, it’s actually been thirty years, because it all started when I won Second Prize at the Leeds Piano Competition back in 1990. Northern Sinfonia were one of the first major orchestras that got me out there doing concertos; shortly after The Leeds I came back and did Beethoven Four with Heinrich [Schiff], and it all developed from there. I have very fond memories of those early days, and even though most of the players are different these days I still feel a real sense of continuity. Over the next twenty years or so I came back now and again as a soloist, including a tour of Germany and Holland with Thomas Zehetmair conducting the Second Brahms Concerto. Then in 2013 they offered me a play-conduct gig, just as that was becoming a passion that I really wanted to pursue. There was an amazing openness right from the beginning, and just before we went on for the concert they asked if I wanted to be their next Music Director – it was quite an astonishing offer, and I’m so grateful for these five years of wonderful experience I’ve had with them.

Do you have your sights set on directing any other concertos from the piano – the Schumann, perhaps?

Oh, the Schumann is wonderful, and actually so much easier to bring off than either of the Brahms! That surprised me at first, because the Schumann concerto’s generally feared among conductors: I conducted it once with a soloist and basically had to relearn the last movement because everything feels against the beat, so if you’re used to performing it as the pianist it’s incredibly disconcerting! If you’ve got a really brilliant conductor like the Daniel Hardings and Robin Ticciatis of this world at the helm it feels like nothing, but otherwise the last movement in particular is so much easier if one just listens and disregards the downbeats.

The Grieg concerto works beautifully, too: the only tricky thing there is the very end, because again you can’t conduct so you have to depend on the brass to keep the tempo for that last tune. The Beethovens and the Mozarts, of course, are known quantities, but I’m also wondering about trying Tchaikovsky One at some point. I did Shostakovich Two with Northern Sinfonia at the beginning of this season (back when we were still allowed to play!) and that worked a treat: it’s relatively straightforward, as there’s really very little freedom once the thing is running! I even played that in the classical position, with the piano out in front rather than facing the orchestra – it’s better in terms of sound and worse in terms of contact, but if you know each other very well then it’s not a problem.

How is lockdown treating you?

I’m actually loving it. In a way I’d been contemplating the idea for a sabbatical for a long time, so I’d already done a lot of thinking about what I would like to learn if I found myself with long stretches of free time on my hands. So on Day One of the lockdown I started learning the Hammerklavier Sonata, which was always a dream of mine – it’s one of those pieces where you really have to sit down for a solid month and basically do nothing else, and I never had the time to do that when I was working! I’ve spent two or three hours with it every day for the past six weeks, but it’s not like I’m doing regular practice-marathons: it’s nice to have a bit of proper family time, and I have a two-year-old who didn’t get to see much of me for the first two months of the year. I try to plan the time between getting to grips with new repertoire and revisiting things like the Liszt Sonata in B minor, which I haven’t touched in ten years and is another piece which takes time to really get into. All things considered I’m enjoying this time a lot.

How do you feel about doing live-streamed performances from home?

I’ve done occasional ones. I started just experimenting with smaller pieces, then I did two proper concerts: the Goldberg Variations on Easter Sunday, and the Beethoven Bagatelles Opp. 126 and 119. There are technical issues, of course: I did buy an external microphone, but there’s no getting away from the fact that the recorded sound for these things is going to be completely horrible! What it does provide, though, is a certain sense of atmosphere: I kind of enjoy the feeling of performing even though there’s nobody in the room. My idea was to make it a weekly thing, but I think I might skip this Sunday!

Lars Vogt (piano/conductor), Royal Northern Sinfonia

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Lars Vogt (piano/conductor), Royal Northern Sinfonia

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC