Interview,

Chen Reiss on Beethoven's Women

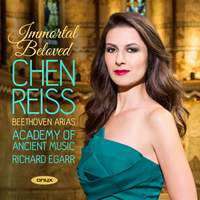

Amid the proliferation of Beethoven anniversary releases, it was a treat to come across an album which introduced me to so much unfamiliar music by the composer - Israeli soprano Chen Reiss’s Immortal Beloved (released on Onyx this Friday), which includes arias from the incidental music for Egmont, Eleonore Prochaska and the early singspiel Die schöne Schusterin as well as the better-known scena Ah! Perfido and Marzelline’s aria from Fidelio.

Amid the proliferation of Beethoven anniversary releases, it was a treat to come across an album which introduced me to so much unfamiliar music by the composer - Israeli soprano Chen Reiss’s Immortal Beloved (released on Onyx this Friday), which includes arias from the incidental music for Egmont, Eleonore Prochaska and the early singspiel Die schöne Schusterin as well as the better-known scena Ah! Perfido and Marzelline’s aria from Fidelio.

In between Chen’s rehearsals for Amélie Niermeyer’s production of Leonore at the Vienna State Opera last month, we spoke about Beethoven’s female muses, the challenges which his vocal writing presents, and his radical depictions of women in his stage works and concert-arias.

At what stage in your career did you start to explore Beethoven's vocal music?

Beethoven was definitely one of my biggest loves early on, but at that stage it was the orchestral and instrumental music rather than the vocal repertoire; Daniel Barenboim has been a huge inspiration, not only through his recordings but also through his live performances in Israel which I saw when I was young. I discovered the vocal music later, and I’m glad about that because I think that one needs more maturity to sing these pieces as they’re not always vocally comfortable. As a young soprano I had very natural coloratura, so the music of Handel and Bach seemed very easy for me - but Beethoven requires much more control of the middle voice, which tends to come later. You really have to keep the legato going, too, because the orchestration is usually somewhat thicker and more dramatic than his contemporaries, even moreso than Schubert: you always have to sing with a little bit more voice, a little bit more air.

The other difficulty with Beethoven’s vocal writing is that in my opinion he didn’t really have a concept of the passaggio. If you look at Italian composers like Puccini, Donizetti and Rossini, they all avoid sitting around the top of the treble stave for too long - they write a lot of leaps from say E to A for soprano, whereas Beethoven will go straight for the F sharp and G and really park there, so one has to have a very clear vocal plan! The Ninth Symphony is a case in point, but the advantage there is that it’s relatively short; it’s even more challenging in the longer scenes on the recording, like Ah, perfido! or Primo amore, which is one of the earliest pieces on the disc. He was about twenty when he composed that, so it’s really one of his earliest attempts at vocal writing: he’s already a master of orchestral writing and his musical language is very distinctive, but the writing for the voice itself is very challenging. It sits very low for long stretches, and suddenly you’re right on the passaggio at forte, so it was a very interesting vocal journey for me.

The album also explores a lighter side of Beethoven, which people might not know so well…

There is definitely more lightness in the earlier works, and there is one piece which is completely buffo – it’s called 'Soll ein Schuh nicht drücken' (from the incidental music for a play called Die schöne Schusterin) and it’s an entire aria about a shoe! I was completely blown away when I first saw the music, and when I read the text I just burst out laughing: I thought ‘I can’t believe that Beethoven would write an aria about such a trivial subject!’. There is a lot of Haydn in it, in terms of the humour and sheer happiness in the music: we tend to associate Beethoven with seriousness, especially in his middle and later periods, but in the beginning perhaps he was more cheerful! If you think that what inspired him later on was something like Egmont - a heavyweight Goethe masterpiece about war, about liberty, about all the ideals that he was fighting for - it seems quite incredible to think that Beethoven would agree to write music for a play about a shoemaker. He wrote that in his early 20s, and it was inspired by another 'Immortal Beloved'; at the time he was infatuated with a soprano called Magdalena Willmann who was the daughter of a neighbour in Bonn, and he wrote her that piece as well as Primo amore. I spoke to the musicologist John Wilson, who specialises in early Beethoven works, and he said that he’s quite sure that he wrote it for her, and that she probably asked him to write it: she had a very strong chest-register, and this is why these pieces have some really low notes for a soprano.

The role of Marzelline (whose aria is included on the album) figures prominently in your schedule for this anniversary year, both in Fidelio and its precursor Leonore: how different is the character in the opera’s earlier incarnation?

They're very different, and I was quite surprised to discover that myself. The 1814 Fidelio is much shorter than the three-act version from 1805, where Marzelline is a much bigger role, both dramatically and musically. There is an additional trio with Jaquino and Rocco, where she makes it very clear to poor Jaquino (as if the duet wasn’t enough!) that it’s not going to work between them: she must say ‘Nein’ about two hundred times! It’s very unusual for Beethoven, because it’s really quite buffo in the interaction between the characters: the whole beginning of the opera with the duet and then this trio is very much on the lighter side. Then in the second act she has a beautiful duet with Leonore, and I do wonder why Beethoven cut that later on, because it’s very good music. What I love about it is that it’s like chamber music in that it’s almost a conversation between four voices: as well as the two vocal lines you also have two solo instruments, the violin and cello, who play gorgeous solos. The lines are very lyric, and it actually does sound like earlier Beethoven, so me for me it was very interesting to do it in connection with this album, which includes a lot of very early pieces – as early as 1791, from the time he was still in Bonn.

In the aria we see that Marzelline is a girl who is head-over-heels in love and who has a wild imagination – but also that she is very much a girl of her time who knows her place. There’s a particularly telling line where she reflects that a woman cannot say everything that she feels: ‘Ein Mädchen darf ja, was es meint / Zur Hälfte nur bekennen’. She has a romantic, very homely way of seeing marriage, and in the Leonore duet she goes even further: the words are completely anti-feministic and quite shocking to women of our time, because she says ‘Nur was du willst, soll stets geschehen / Ich gebe deinem Willen nach’ (‘I must agree with everything that you say, I will always do everything that you want’). And she says all of this to the disguised Leonore, who of course sees married life in a different way and is taking her life into her hands to rescue her husband...for me, Marzelline’s role in the opera is to highlight just how brave and radical Leonore is in comparison with more conventional women of that period.

Might the role of Leonore attract you further down the line?

Perhaps. I wouldn’t do the Fidelio Leonore, because traditionally that’s sung by much heavier voices -Birgit Nilsson sang it, and as Marzelline I’ve been on stage with enough Leonores to know how demanding the role is. But I would maybe consider singing Leonore in the earlier version: it very much depends on the venue, the orchestra, and the rest of the cast. I think that Leonore could really work very well with a period orchestra, and then I would certainly consider it, as in that context Beethoven’s writing feels closer to Mozart than to Wagner: with period instruments you sing differently, and you’re also usually performing in smaller spaces, with singers with less vibrato. There’s also the question of tempi: René Jacobs’s tempi on his new recording of Leonore are very different to those of Karajan or Bernstein in Fidelio, and that’s also very significant from a vocal point of view.

Are there prefigurations of Leonore in the other, lesser-known characters we meet on the album?

Yes. This is why I called the album Immortal Beloved, because the arias that I chose show very strong women: women prepared to go to war, like Eleonore Prochaska who actually went into battle and was killed, and Klärchen in Egmont who says that she wants to dress like a man and fight alongside her husband. Even in Ah, perfido! we see a woman who refuses to accept her beloved's behaviour: she curses him and calls on the gods to punish him, but then she retracts that and declares that he remains her greatest love. These are women who are very loyal, but they’re by no means weak; they’re actually quite tough, and in my opinion such women hardly existed in Beethoven’s time. In today’s society women don’t really need men any more, even to have children: we’re completely independent, and if we have a man in our life then it’s because we choose to, but in the nineteenth century of course women didn’t have that freedom. So Beethoven really pushes the boundaries in his depictions of women, in the same way that he pushed them in the length and structure of his symphonies and piano sonatas and string quartets: in his vocal music, too, he takes a step further in every way.

Chen Reiss (soprano), Academy of Ancient Music, Richard Egarr

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC