Interview,

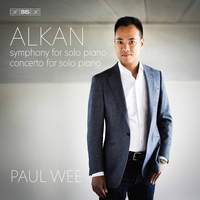

Paul Wee on Alkan

It's not every day that a new recording of Charles-Valentin Alkan's prodigiously difficult solo piano works emerges; both the Symphony and the Concerto pose immense technical challenges. It's rarer still, though, for such a recording to be undertaken by someone whose primary career focus isn't even music at all. Alongside numerous concerts and recitals, Paul Wee's CV includes prominent court appearances representing, among others, global banks and major nation-states - because when not behind the piano, he is a highly successful lawyer with specialisms including energy disputes and international law.

It's not every day that a new recording of Charles-Valentin Alkan's prodigiously difficult solo piano works emerges; both the Symphony and the Concerto pose immense technical challenges. It's rarer still, though, for such a recording to be undertaken by someone whose primary career focus isn't even music at all. Alongside numerous concerts and recitals, Paul Wee's CV includes prominent court appearances representing, among others, global banks and major nation-states - because when not behind the piano, he is a highly successful lawyer with specialisms including energy disputes and international law.

Perhaps inevitably, interest in his new recording for BIS of these two daunting peaks of the piano repertoire has focused on the seeming impossibility of pursuing in parallel two careers, each of which by itself might be considered intellectually challenging enough for all but the most formidably gifted. I spoke to Paul about his choice of repertoire, and the interactions between his two worlds of law and music.

These are an interesting pair of pieces to choose for your recording début; how did you first come across, and evidently become very attached to, Alkan’s music?

Yes – I was actually a little surprised that the Symphony and the Concerto hadn’t been paired on a single-disc commercial recording before! I was first introduced to Alkan’s music as a teenager, when I heard a live recording of Marc-André Hamelin playing the Symphony for Solo Piano, and was immediately awestruck by its dramatic intensity. Alkan’s epic narratives – such as the Symphony and Concerto for Solo Piano, the Grande Sonate, and the Sonatine – are staggeringly powerful works, which pull you in and refuse to let you go. This flows from the cumulative impact of Alkan’s mastery of form, natural gift for melody, and unparalleled pianistic ingenuity.

The Alkan symphony seems like a pianist’s equivalent of Widor and Vierne’s Organ Symphonies – an imaginary “transcription” of a non-existent orchestral original. Do you find yourself mentally ascribing specific instrumentation to different passages when you’re preparing this work?

The analogy to the organ symphonies of Widor and Vierne is spot on. In the piano literature, there is one further link in the chain: these are piano transcriptions of (actual) orchestral symphonies, such as Liszt’s transcriptions for solo piano of Beethoven’s symphonies. There, Liszt didn’t simply distil the orchestral score to a playable piano reduction, marked with directions like “quasi celli”, “quasi flauti”, or “quasi tromboni” to communicate the desired sonorities. Instead, he took the colours and contrasts of the orchestral originals, and reconceptualised them anew in the language of the piano, utilising uniquely pianistic techniques and effects. So too with Alkan’s Symphony: this contains a vast range of colours and textures, all of which must be differentiated if the music is to be brought to life. But this can only be delivered through the language of the piano. So mental analogies to specific instrumentation can be helpful, insofar as they may help a performer to imagine certain colours or contrasts to convey. But I think this process can only go so far. Since these colours and contrasts must be realised in the language of the piano, I ultimately approach this music through the sounds and colours of the piano, with an eye on the various techniques used to achieve them.

A concerto for solo piano brings with it a seemingly obvious conundrum – how do you achieve the sense of dialogue between “soloist” and “orchestra” when they are both the same person at the same instrument?

First and foremost, this effect depends on the craftsmanship of the composer. The credit here lies with Alkan: the duality between soloist and orchestra has been written masterfully into the score of the Concerto for Solo Piano, in which the passages depicting orchestral tuttis are cast in fundamentally different textures and writing from the passages depicting piano solos, and in which the passages simultaneously pitting orchestra against soloist somehow – miraculously! – superimpose these different textures on top of each other, enabling each to be distinguished and heard.

This aspect of Alkan’s genius can be highlighted by comparing his efforts in this field to those of other pianist-composers. Take Mozart’s famous D minor Piano Concerto, which was arranged for solo piano (and so as a “concerto for solo piano”) by both Alkan and Hummel (a very inventive pianist in his own right). Hummel’s transcription successfully condenses the content of the orchestral and solo piano parts into a playable piano reduction. But there is little, texturally or pianistically, to distinguish between orchestral tuttis, solo passages, or ensemble playing. Yet Alkan’s transcription differentiates orchestra from soloist with a startling three-dimensional clarity, and brings Mozart’s numerous passages of delightful dialogue between soloist and orchestra to life with a sparkling wit that is as much Alkan as it is Mozart. This same three-dimensional writing runs through the entirety of the Concerto for Solo Piano.

One fascinating aspect of how Alkan accomplishes this can be revealed by comparing the Concerto with the Symphony, which actually display very different approaches to pianism. The writing in the Symphony is generally chordal and vertical, and largely eschews conventional pianistic figurations. Conversely, characteristically pianistic figurations – such as scale-based passages and other rapid fingerwork, or long right-hand melodic lines carried over gently undulating left-hand accompaniments – abound in the Concerto, and form hallmarks of many of its “solo piano” passages. So Alkan achieves the three-dimensional effect of the Concerto by using the textures and techniques that are most characteristic of the piano to highlight the solo piano passages, while clothing the orchestral passages in the very different textures that Alkan uses to construct the Symphony. That is a further reason why I think these works form a fascinating pairing.

Of course, all of this can only be brought to life by a sympathetic interpreter with a sensitive ear. It is necessary to understand both the effects that Alkan is trying to achieve, and the precise way in which he seeks to do this. And this is just one of the many ways in which a convincing performance of the Concerto requires far more than merely navigating the notes on the page.

Both these pieces are contained, at least nominally, within Alkan’s set of minor-key études; thus all seven movements are based in the minor. Do you find that there’s enough light within the music to relieve what appears on paper like quite a lot of minor-mode darkness?

The Symphony and the Concerto each contain more than enough contrast to make any listener forget their technical status as études in the minor keys. In the Symphony, much of this contrast derives from weight. The opening Allegro is one of the great Romantic epic tragedies, culminating in a cataclysmic climax of darkness triumphing over light. Both the ensuing funeral march and minuet movements feature major-key trios, which let in some much-needed relief from the minor key tonalities that have dominated. And although the finale is also set in a minor key, this manifests its character in the flying of sparks and the flickering of flames dancing across the sky, rather than in evoking the blackness of the abyss. This is minor-mode darkness as lightness and energy.

The light in the Concerto is much more obvious. Although the first movement’s key of G-sharp minor is duly reflected in its opening fanfare, much of this movement is spun out from its deeply lyrical and major-key second theme. Even the opening minor-key fanfare sees some striking transformations into the major. And after the extraordinary cadenza concludes with its illusion of rapidly repeated lower notes deep in the bass (actually a trill), the movement ultimately turns away from the minor and towards the light, building up to a colossally blazing conclusion in A flat major, a tonality which is proclaimed as emphatically and mightily as the major-key conclusion to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. The following Adagio in C sharp minor is admittedly a work of the deepest darkness, which spins its haunting lamentation into a raging tempest that unfurls into the drums of a funeral march. But this is then followed by another remarkable finale, which opens with a flourish in the “wrong” key of D major, which pivots (via chromatic sidestep) into its “correct” home key of F sharp minor. As with the Symphony’s finale, this is minor-key tonality as lightness and energy. And as with the first movement of the Concerto, this too ultimately renounces its minor-key tonality, and builds into a coruscating conclusion of F sharp major. So by the end of the Concerto, there can be no doubt that light has prevailed over darkness.

Many people will first have come across your name accompanied by descriptions of you as “the pianist lawyer” or vice versa. Do you find any of the mental skills involved in one of your twin careers transfer into the other sphere?

Absolutely! Both fields rely heavily on powers of memorisation, as well as logic and analysis. On the musical side, the latter is not only the bedrock of understanding structure and form, but also of solving technical problems. However, there are three more interesting ways in which these two fields cross-fertilise which I’d like to highlight instead.

The first concerns the process of interpretation. This is central to both of these fields – whether one is interpreting a Beethoven piano sonata, or interpreting the law on expropriation through judicial action. The concept of “interpretation” is frequently invoked in musical discussion, if often without any meaningful account of what this concept is supposed to entail. My legal studies exposed me to the work of the legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin, for whom the concept of interpretation was central to the concept of law. In his work Law’s Empire (1986), Dworkin posited a theory of creative interpretation, which is the most persuasive and enlightening account of the process of interpretation of which I am aware. This account is readily applicable to musical interpretation, and provides the framework in which I approach questions of interpretation as a musician (“should that lengthy exposition repeat be taken?” “how should the composer’s pedal markings be treated, when they were written for a very different instrument to the modern piano?” “when is it legitimate to re-distribute notes between the right and left hands?” “what really is the significance of the composer’s intentions, to the extent that they can be reliably discerned?”). So I think my legal background (and Dworkin’s account of creative interpretation in particular) has placed my understanding of the process of interpretation, and what it entails for a musician, on a firm conceptual foundation.

The second concerns the task of persuasion. As a barrister, my role is to persuade a judge or tribunal of my client’s case; as a pianist, my role is to persuade an audience of (my interpretation of) the works I am performing. I know from my legal career that it isn’t always possible to succeed in this task! Fortunately, music isn’t as binary as law, and there isn’t always a winning side and a losing side. But I think it is healthy and humbling to be reminded that no matter how persuaded I may be of the merits of the repertoire I am playing, or my interpretation of that repertoire, I may not always be able to carry the entirety of the audience with me – although that is of course always my goal.

The third concerns the act of performance. The performance element to my life as a pianist is obvious. But every appearance in court is a performance, too: you have one chance to persuade, cross-examine, and get things right; and a winning performance can make all the difference. Whether as a pianist or barrister, the success of any performance turns on both careful preparation, and execution “in the moment”. Nothing can be taken for granted, and risk is always present. Just as any pianist will have rued a missed note, every barrister will have wished they had asked a slightly different question to a witness, or given a slightly different answer to a query from the judge. I think that in both of my careers, it is important to enjoy and thrive on this performance element, and to harness the adrenaline and energy that it brings as a force for good. And I know that the satisfaction that follows a successful concert or hearing can feel remarkably similar!

Do you limit yourself to solo recitals, or are there chamber music and concerto performances in the mix as well?

I very happily play all three. As well as playing solo recitals, in recent years I’ve performed a handful of concertos by Beethoven, Chopin, and Mozart; and on the chamber music front, I’ve been performing semi-regularly in recent years with Damian Falkowski, a violinist and fellow barrister-musician who trained at Juilliard and played professionally for many years before turning to the law. All of this has been immensely rewarding. In solo repertoire, a pianist has total interpretive control and executive responsibility. This can be daunting, but also very satisfying. Yet there’s nothing like the joy that comes from creating music with others in a chamber music setting.

Major logistical questions spring to mind when one thinks about the need to put in the hours at the keyboard while working in a profession where working long hours is standard. Where and how do you get your practice in?

This is very difficult. I am a barrister first and foremost, and a career as a commercial barrister is very demanding. My clients know that I give all of my cases the full attention that they require, and this means that I frequently go for weeks at a time without touching a piano. Even putting such extreme periods to one side, I certainly don’t manage to play every day; one or two good sessions each week at the keyboard is probably the most that I generally aim for (and don’t always manage to achieve). I’ll usually practice at home, where I have a grand piano and a Yamaha Avantgrand hybrid piano for late-night practicing (a lifesaver!). Over the years, Gray’s Inn (my Inn of Court) has also kindly permitted me to use the Inn’s piano in Hall for practice when it is not otherwise in use, which has also been invaluable. All that said, music and the piano are my passions and constantly on my mind, even when I’m not able to spend time physically at the keyboard, and there is so much useful work that can be done away from the piano.

When I am preparing for a concert or a recording session, I approach this in the same way as my professional commitments, and manage my diary in the run-up to ensure that I find the necessary time to prepare. It’s actually when I don’t have any imminent piano-based commitments in my diary that I find that I play least! When my professional and musical diaries permit, I find that spending time to unwind properly, whether alone or with family and friends, is most important of all.

Paul Wee (piano)

Available Formats: SACD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC, Hi-Res+ FLAC