Interview,

Stuart Skelton on Wagner

I received a few sceptical looks when I mentioned to my colleagues that I was off to talk to Stuart Skelton about his recording his first solo album and making his Royal Opera House debut last month: given the Australian dramatic tenor’s impressive discography of opera and oratorio recordings and his glowing track-record at many of the world’s major opera-houses, most of the Presto team assumed that both of these things had already happened years ago. But the current Covent Garden Ring Cycle (in which Skelton sings Siegmund) and Shining Knight (a recital of Wagner, Griffes and Barber with the West Australian Symphony Orchestra on ABC Classics) are indeed milestones for one of today’s greatest interpreters of roles like Parsifal, Otello and Peter Grimes; I met up with him in between production rehearsals for The Ring to discuss finding his niche as a Wagnerian, and how Wagner’s legacy played out in the hands of twentieth-century American composers.

I received a few sceptical looks when I mentioned to my colleagues that I was off to talk to Stuart Skelton about his recording his first solo album and making his Royal Opera House debut last month: given the Australian dramatic tenor’s impressive discography of opera and oratorio recordings and his glowing track-record at many of the world’s major opera-houses, most of the Presto team assumed that both of these things had already happened years ago. But the current Covent Garden Ring Cycle (in which Skelton sings Siegmund) and Shining Knight (a recital of Wagner, Griffes and Barber with the West Australian Symphony Orchestra on ABC Classics) are indeed milestones for one of today’s greatest interpreters of roles like Parsifal, Otello and Peter Grimes; I met up with him in between production rehearsals for The Ring to discuss finding his niche as a Wagnerian, and how Wagner’s legacy played out in the hands of twentieth-century American composers.

Did you always have an affinity with Wagner, or were you warned off exploring it too early?

No-one actually ever warned me off! I consider myself very lucky in that regard. I came to singing a couple of years later than my grad school colleagues, but my teachers in Cincinnati were quite open about the fact that they thought Wagner was where I was headed, and their approach was: ‘Why don’t you learn it here and now, where it doesn’t matter and you’re not going to have to sing it in a big auditorium? We’ll work on getting the language and the idiom right, so that when the time does come (and we suspect it will), you’ll already have parts of these roles bubbling away’. They showed incredible foresight, I think, because usually if a graduate student rocks up talking about Wagner everybody says ‘Put that away! What are you doing not singing Mozart?!’.

That’s not to say that heavier voices can't or shouldn’t sing Handel and Mozart (one of Jon Vickers's great legacies was Samson, and Ben Heppner sang Tito and Idomeneo), but I’m very grateful that the people I was working with weren’t interested in ticking boxes or shoe-horning me into something I wasn’t; Don José in Carmen was one of the very first things I did, and roles like Lensky in Eugene Onegin are also great for embryonic dramatic tenors.

At what point did you take Wagner out of the controlled conditions of the practice-room and put it out there on a professional stage?

I sang my first Lohengrin when I was 31 (I think Johan Botha was around the same age), but my Wagner debut was as Erik in Flying Dutchman; that was in Strasbourg, back in 1999/2000, and Lohengrin happened in Karlsruhe in late 2000. The house offered me two performances at the end of a run, with the option of singing all the performances in the revival the next season if I was comfortable. I remember calling my singing-teacher Barbara in Cincinnati when the contract came through, and her response was ‘Are they paying you? And is there plenty of rehearsal-time? Yes? Then why are you calling me?!’.

What did you learn from that first experience of singing a major Wagner role?

Lohengrin really taught me to sing, because I had to learn how to spread my vocal resources over a much longer period of time than ever before. Wagner always puts the most demanding stuff in the last act: that’s true not just for Lohengrin, but also for Wotan and Brünnhilde and for Gurnemanz in Parsifal (which is by far the monster role in that opera – Parsifal is actually relatively short in terms of singing-time). When I voiced those concerns to my teacher, she said ‘You’ll learn! Your body will work out what it needs to do, and when you can rest, and how you go about resting, which is just as important’. And I did - but when I did my first Tristans in 2016 I learned all of that again, because Tristan is a completely different animal. It’d been a long time since I’d sung anything where my voice found the edge of where it could go in a single evening; in the rehearsal process my voice would get to a point when it said ‘I’m done for the day!’ and I’d think ‘But we’ve got three pages left!’. When you sing Tristan you will hit the wall, and like a distance-runner you have to work out how you negotiate that wall when you get there – ideally, it happens just after you sing that final ‘Isolde!’ and collapse in a heap! I just did it in Perth and the wall came after I’d finished singing, pretty much for the first time. Your body gradually learns how to stack up underneath the voice, and muscle-memory does far more for you than any amount of intellectualising about technique.

You talk in the booklet-note about tracing a path from Wagner’s Italianate beginnings with Rienzi through to the later works - do you feel that the bel canto influence is still detectable in Tristan and Parsifal?

Absolutely! I think the obvious stretch in Tristan (apart from the Liebesnacht, which could be the Act One love-duet from Otello) is when he sings ‘Wie sie selig, hehr und milde’, and there’s nothing going on in the orchestra. But Rienzi is far more obviously bel canto in terms of its harmonic structure. Wagner was a huge fan of Bellini and Meyerbeer; he never admitted to liking Meyerbeer, of course, but if Rienzi isn’t a French grand opera then I don’t know what is! If you played the opening tune on a piano and asked someone to guess who wrote it, no-one would pick Wagner - they’d swear it was Bellini, Meyerbeer or Donizetti!

And those little turns in Rienzi's Prayer are straight out of a bel canto aria...

Exactly! He always kept those turns – he has them in Lohengrin and Dutchman, and even in Tristan he has appoggiaturas...he never really lost that thread of bel canto. But the really fascinating thing about Rienzi is that every now and then you hear two or three notes in the orchestra or the vocal line that show you where he’s headed. At one point Rienzi says ‘I put my hands into the pool of blood that was flowing from my brother’s heart...Woe to anyone who feels they don’t need to avenge that’, and out of nowhere we get a snatch of the Todesverkündigung (Brünnhilde's annunciation of death from Die Walküre), but that’s all it does! He’s already toying with these nascent glimpses of things which we know are going to come back in his mature works, and I think Rienzi is a terrific piece for that reason alone; I’d love to do it here, it’s so much fun!

You’ve got no Tristan on the disc – is that because we have the Wesendonk-Lieder instead?

The honest answer is that we’ve just recorded a complete Tristan live in concert with the West Australian Symphony Orchestra and an amazing cast; Gun-Brit Barkmin as Isolde, Ain Anger [who’s Hunding in the Royal Opera House Ring] as King Marke, and Ekaterina Gubanova as Brangäne. And it’s hard to excerpt Tristan – it’s hard to excerpt Wagner in general, but with Tristan you think ‘Oh, can’t we just play the next three or four pages, I mean ‘next four hours’…?!’.

Do you think there's still resistance to men singing the Wesendonks?

I think Jonas Kaufmann really put that issue to bed a couple of years ago! They were written ‘for’ Mathilde Wesendonk in the sense that they set her poetry: he didn’t write them for her to sing! I understand purists will take issue with it, but I think they offer such remarkable insight into his mind as he was figuring out how all of this was going to work in Tristan. Everyone points to ‘Träume’ because of the melody (which actually isn’t particularly ground-breaking), but I think ‘Im Treibhaus’ is much more interesting – for me that’s the pivotal song in the cycle, and of course it reappears in the Vorspiel to Act Three of Tristan. And they’re actually quite fun to sing: the poetry’s not great (we’re not talking Rilke or Heine here!), but he sets it really well.

Will you ever take on Siegfried or Tannhäuser?

No! I’ve probably missed my Tannhäuser window: I’m not quite as flexible as I would need to be to do that now, because Tristan does cost you. There are sacrifices you have to make over time, and that’s fine. I did Act Three of Siegfried in concert five or six years ago, and was really happy with the way it felt, but I knew that I couldn’t do all three acts in a day, and I still can’t. And there’s a certain sound that I always expect from a Siegfried which I don’t necessarily have – a sort of youthful incisiveness to the voice. The other thing is that I don’t actually like him very much: he’s had a rubbish upbringing, but his solution to every problem is to kill it! I also have a lot of trouble getting past the way he treats Wotan in the third act, when he just says ‘Get out of the way, you old fool!’. By Götterdämmerung he’s matured a bit (though he still sees things in very simplistic, didactic terms), but in Siegfried he’s one step away from a lager-lout with an ASBO.

How did you discover the Griffes cycle, and what connections do you see between those songs and Wagner?

I came across them in grad school, when one of my mates sang them as part of a concerto competition. (Interestingly, for Americans this type of repertoire is at their fingertips the whole time: I guarantee every conservatoire in the US has somebody who’s done them in a recital!). My immediate reaction was ‘I need to learn these songs!’, but I’ve sat on them as repertoire for years, waiting for the right time…then serendipity kicked in when I was approached about doing the Wesendonks and we needed something for the second half. I thought it would be a great idea to include at least one composer that comes after Wagner where the influence is obvious, so we could trace a little bit of an overarching survey of Wagner at his most youthful through to his most mature, and then look at the way he hands off that harmonic language and what the rest of the world does with it.

It sounds like you've nailed your Wagnerian bucket-list already, but are there other roles you'd like to tackle further afield?

I’m now in the fortunate position where I've pretty much done everything that I want to do! My wish now is to pick up some of the things I haven’t done as frequently: I’d love to go back to Hermann in Pique Dame and Canio in Pagliacci, and I’m getting to revisit Otello which is coming up in November in New York.

Stuart Skelton appears in Die Walküre at the Royal Opera House tonight and on 18th and 28th October; the final performance will be broadcast live into cinemas around the world.

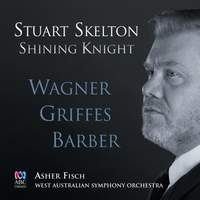

Shining Knight: Wagner, Griffes, Barber

Stuart Skelton (tenor), West Australian Symphony Orchestra, Asher Fisch

Shining Knight was released on ABC Classics on 21st September.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Mahler: Das Lied von der Erde

Magdalena Kožená (mezzo), Stuart Skelton (tenor), Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, Simon Rattle

Das Lied von der Erde was recorded live in Munich this January, and released on BR Klassik last month.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC