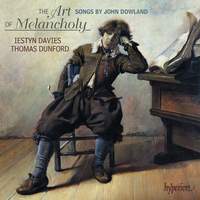

Interview,

Iestyn Davies on singing Dowland

British countertenor Iestyn Davies talks to Presto's David Smith about his new Dowland recording, The Art of Melancholy, out on 31st March on Hyperion Records.

British countertenor Iestyn Davies talks to Presto's David Smith about his new Dowland recording, The Art of Melancholy, out on 31st March on Hyperion Records.

Your last disc for Hyperion (Arias for Guadagni) was a compilation; what drew you particularly to an all-Dowland album this time?

>I could have made an album called "The Art of Melancholy" that had a variety of Elizabethan/Jacobean composers but it wouldn't have fitted with my theme - with Dowland I sensed there was a personal narrative behind his songs. It's not an uncommon suggestion and has frequently been brushed off by scholars; in particular some have driven back the notion that there is any ground in trying to analyse Dowland as if he were on the psychotherapists' couch. I disagree with this in part as I do feel that there is something to be gained from empathising with someone who professionally was rejected at court, driven to seek work abroad at at time when travel was dangerous and uncertain [...] and ended up playing for a foreign King hundreds of miles north of London in the rather icier climes of Copenhagen, not to mention being geographically ostracised from his wife and family.

>Freud was clear that Melancholy and Mourning were connected and that experiencing a 'lack' in one's life [...] can provoke periods of prolific artistic production [...]. To put a programme together of Dowland's music such as this is to question what we mean when we say 'melancholy'. It is evident that it is not just about a depressive state, but rather about expression at an intense level.

>These songs are the Art that comes from Melancholy. When a melancholic attains a goal or works through their Mourning it is common that this artistic expression noticeably 'dries up'. When Dowland finally got to work at the English Court for James I from 1612 there are few compositions until his death in 1626; perhaps professional satisfaction settled his active mind.

Compared to “Arias for Guadagni” and the Handel arias, the songs on this album are much less extrovert, much less virtuosic. Did you miss the chance to show off with vocal fireworks?

>It is interesting to think about this idea of 'fireworks' in baroque music. We know Handel wrote skilfully for the singers he employed - it was evident that with Guadagni even those arias which you could describe as 'fireworks' are not in fact anything like as grandstanding as those written for Senesino for example.

>The strength of these songs is in the deployment of much more interesting and equally demanding technical attributions; those of legato line, breath control and even more attention to word painting. So on the one hand, yes there are fewer chances to 'show off with vocal fireworks' but on the other hand as one conductor once explained to me 'my wife likes it a great deal slower'.

Your previous solo albums and recordings have been with orchestras or ensembles; how different was it to sing with just a lute to accompany you?

>From a very boring and practical level in terms of recording (as I'm used to performing concerts with one other person, so that is nothing new) it is a completely different process from recording with a group or orchestra. You are no longer at the mercy of strict session timings and enforced tea breaks, a necessary evil in the process of making art and earning money at the same time. So this gave me and Tom a luxury when it came to deciding when and what to record. We were recording in the quiet Suffolk countryside too as such a delicate and quiet duo can't deal with traffic and distractions of London that perhaps a larger orchestra may drown out. This added to the sense of timelessness to everything which makes sinking yourself into the Elizabethan mindset just that bit easier.

>Musically of course a duo is as strong a partnership as you can get and I can't really believe how lucky I've been to be around at the right time to be able to meet and work with Thomas Dunford. [...] He is a wonderfully natural musician who responds as a partner with the unteachable quality of telepathy that only few display with such ease. [...]. As I always think, it's like breathing together with somebody, we share the same sense when we meet a potential partner in life, where the 'chemistry' is just there and you can't escape it. He's also a fantastic technical player, which goes without saying with this incredible repertoire.

At first sight this album presents quite a sombre picture; the popular image of Dowland is as a permanently miserable, downcast individual. Do you think this is fair, or has posterity been a bit unkind to him?

>I think we are to blame here for not really understanding what we mean by 'melancholic'. [...] Elizabethan Melancholy was a fashion to be worn on one's sleeve. It was not necessarily as plainly understood as we tend to make it nowadays. It was as if in the 16th and 17th centuries there was an ardent suggestion that life and death, gain and loss were opposing sides of the same coins and could so easily land face up as face down. This has somewhat masked the appraisal of Dowland's character, distracting us from perhaps a more interesting suggestion (as mooted above) that true 'melancholy' displays itself in a less two-dimensional form.

>The songs in both the music and the poetry are mere hints at the composer's own character but they are equally beyond measure within the realm of the other composers of the day and I have enjoyed entertaining the idea that his genius was spurned on by something more than fitting in with the fashions of the day. Where for example, where on earth does "In Darkness Let Me Dwell" come from? There is nothing else quite like it and it bears the fingerprints of a troubled mind but one whose skill was beyond compare.

Do you have a favourite out of the songs on this album?

>I would be lying if I didn't say 'In Darkness Let Me Dwell' is one of the greatest songs written in the English language. It is also a joy to sing simply for the range of expression within the vocal line. [...] He writes so well for certain moods. Nothing beats "Come Heavy Sleep" when you are at the end of the bottle, weary eyed and longing for repose and who cannot fail to be charmed by the simple yet infectious beauty of "Now O Now I Needs Must Part".

>I'd advise anyone new to this repertoire or indeed those who think they know it to pick at random a track and get to know it - every listening brings something new, a new layer of musical brilliance or a curiously double meaning in the poetry. This is music out of time, it's music that I feel has its roots in the conventions of historical performance but sprouts its fruitful leaves well beyond those boundaries.

The Art of Melancholy is released at the end of the month and is now available to pre-order. You can also view a short video-interview with Iestyn by clicking on the image on the left.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Other recent recordings from Iestyn Davies

Arias from Belshazzar, Esther, Semele, Jephtha and others, accompanied by The King's Consort under Robert King with two guest appearances from Carolyn Sampson

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Iestyn is joined by young ensemble Arcangelo under Jonathan Cohen for this programme of arias written for the Italian alto castrato Gaetano Guadagni, who created the title-role in Gluck's Orfeo and Didymus in Handel's Theodora; the disc includes excerpts from these works as well as music by Arne, Hasse and Guadagni himself.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC