Interview,

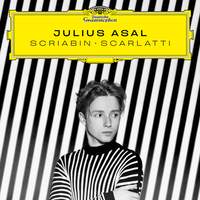

Julius Asal on Scarlatti and Scriabin

What struck me the most about his performance that evening was the mesmerising quality of his soft playing (here's an artist who can conjure an astonishing range of colours within the confines of a pianissimo marking) and the almost uncanny coherence of a sequence built around two such outwardly different composers - at times it was difficult to tell where Scriabin stopped and Scarlatti (or indeed Asal's own thoughtful responses) took over.

I met up with Julius on Zoom ahead of the album-release last week to discuss why he's 'always been drawn to the darker side of things', the connections which he feels between these two composers who seemingly inhabit 'different universes', his love of improvisation, and how playing the piano became his 'first attempt at communication' as a toddler....

Scarlatti and Scriabin make for quite an unconventional pairing! What do you see as the common ground between the two?

It’s really hard to describe, because it stemmed from an inner feeling rather than something more rational. Hopefully the pairing will provoke some inner feeling in the listener too, which could be different from mine - there’s no recipe! These two composers of course come from different times, different countries, different universes really…but I felt there was something that they both share, and that’s the desire to create something genuinely new.

At the centre there is the Piano Sonata No. 1 by Scriabin, which is very seldom played - and I don’t understand why because I think it’s so brilliant - and I felt like there is some connection to those two F minor sonatas by Scarlatti which I recorded. The strange thing was that once I dived in, I started to find all kinds of other connections: for example, the last notes of that furious Prelude in B minor by Scriabin are exactly the same notes which we hear at the beginning of the Scarlatti sonata which comes immediately afterwards on the album.

And of course I selected the programme to underline those connections. A lot of Scarlatti’s music is very bright, full of euphoria and positivity, but I actively tried to find sonatas which match the darkness that’s often present in Scriabin. (There are over 500 of them, so I had plenty to choose from!).

Do you come from a musical family?

My mother is a pianist, my father plays clarinet, my brother’s a jazz and pop drummer, and my grandma was a pop-singer – it’s everywhere! But my parents never taught me music: in German we have this word ‘Rollenkonflikt’ which we try to avoid, and for that I’m very thankful.

I started playing the piano of my own accord just before my third birthday: I didn’t even talk at that stage, so in a way music was my first attempt at communicating. My parents had actually been worried that I might have some kind of problem with my hearing, but then they noticed that I would play back melodies I heard and they realised that this was just my way. I couldn’t read any scores at that age so I just played everything by ear, and that was how it continued until I got my first lessons.

Is playing by ear and improvising still a part of your musical life?

It’s something I’m coming back to these days, partly through my work with Deutsche Grammophon. It’s beautiful to connect existing classical pieces with something which actually happens in the moment, and shine a new light on pieces that have been played so many times by so many brilliant people.

Which musicians have influenced you on your journey so far?

I always feel that I’ve been quite lucky with my teachers and mentors, because everybody seems to have come into my life at the right moment. In the beginning I studied with Sibylle Cada and Wolfgang Hess in my home-town of Frankfurt, and they opened up doors to the formal classical music way: rather than just improvising and thinking about sound on my own, I learned to channel my musicality, get a grip on reading scores and understand some of the underlying structures.

Over the last few years my work with Eldar Nebolsin and András Schiff has influenced me enormously: I studied with András at the Kronberg Academy for three years, but we’ve actually known each other for seven years and he’s just great! And getting to know people like Gidon Kremer was so important: in fact we’re meeting up next month in Kronberg to play a piece by John Harbison. I learn so much from these people: it’s a whole universe to me.

Speaking of people coming into my life at the right time, I must mention Christian Badzura, my producer at Deutsche Grammophon. At some point Christian contacted my management, and asked if he could come to hear one of my concerts. We met afterwards over a good glass of wine and talked about music.

One thing which caught my attention at your Yellow Lounge performance was the special quality of your very soft playing: do you find that certain models of piano work best for that?

It didn’t really bother me when I was younger, but I’m getting more and more picky. I wish I could be a bit more relaxed about it sometimes because getting too caught up in it can be distracting, but it’s so hard to find a piano that can do exactly what you want. We’re talking tiny details, but the more you work on your idea of the sound you want to create then the choosier you get!

We had two Steinways for the album: we recorded at the Teldex Studios in Berlin, and we couldn’t decide between them because they were so different. One was like a very good, dark red wine with lots of body and character, and the other was like a super-fast car! I didn’t want to compromise on sound-quality, so I recorded most of the album on the warm Steinway and a couple of pieces on the other. The sound engineers had to work quite hard to create the sense that it’s still one unit, because that’s the main idea of the album: everything flows together, everything's like one breath.

Speaking of flow and breath, do you practise any kind of meditation or yoga to keep yourself grounded?

I feel like what I’m doing most of the time is some kind of meditation: not only the act of playing the piano, but also being alone a lot. I don’t mean just being on tour as a soloist - which can be quite lonely in itself - but also the process of working out musical ideas, which involves a lot of mindfulness and self-reflection. I do try to have some kind of physical work-out most days, though, so I don’t get too locked in my own head!

Is solo repertoire your main focus at the moment, or do you still get time to play with others?

I did a lot of chamber music for many years and I learned so much from it, but right now I don’t have the time to focus on it as much as I did before. I’ve come to realise that communication through music still happens when you’re on stage alone for two hours – it just happens inside - but it improves through making music with other people, and that’s very important to me.

Right now I’m working on the Rachmaninoff Cello Sonata with a friend, for an informal performance: I just needed to learn that piece because it’s so good! It’s so wonderful to make music with friends and discover things that are new to you both; for me, that’s one of the most beautiful parts of what we do.

Earlier on, you mentioned being attracted to the darker aspects of Scriabin and Scarlatti: does that attraction extend to your tastes in literature, cinema and the visual arts?

When I was younger I read a lot of Kafka and Büchner: I’ve always been drawn to the darker side of things, and I think that part of the beauty of what we do as artists is to dare other people to explore it too. I wish the listener to invest something. Showing up to a recital isn’t like going to a gala celebration where there’s a firework-display at the end and you get a big hug. There’s no hug, not every time. Instead, there might be a big question which remains unanswered…

Julius Asal (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC