Interview,

Robert Hollingworth on Benevoli's multi-choir magnificence

No surprise, then, that Hollingworth has retained his taste for all things large and lavish; his latest album with I Fagiolini is big, bold, and Baroque, with Orazio Benevoli's four-choir mass based on Palestrina's motet Tu es Petrus in pride of place alongside works by Benevoli's contemporary Bonifazio Graziani.

I spoke to Robert Hollingworth about this mass and how it came to be - as well as touching on some of the questions around funding and support that all musical groups have to wrestle with. But we started with my asking him - as diplomatically as possible - whether he wasn't trespassing on someone else's territory label-wise...!

The first thing I thought was ‘Coro? That’s The Sixteen’s label…’ There are a few I Fagiolini things from the past couple of years, but this seems to be a new development. There's a slight sense of ‘This town ain’t big enough for the both of us!’ What’s the reasoning behind it?

In fact it’s the very opposite of a turf-war in that they’ve invited us onto their label! Although it’s run by Cath Edwards, Harry’s behind everything. But there’s no issue there: the very opposite, otherwise they wouldn’t have had us on.

The reason Coro specifically is because of all the record companies I’ve ever worked with – actually no, Chandos were good as well – they actually answer the phone and emails! Cath Edwards is an absolute dynamo: every question I ask is properly dealt with. She’s a fantastic person to work with: my own manager Libby Percival, Cath and I have this triangle of communication which means things really get done and developed. For example you’ll note that this Benevoli has come out now, but we only finished recording it on 1st July! That’s a horrific turnaround, but actually it was simply no problem because we all knew what the deadlines were and worked towards it.

But also they give me flexibility to do what I want – and we check in with Harry to make sure that we’re not doing anything that clashes.

In terms of the actual repertoire recorded here, it’s this parody mass on Palestrina’s Tu es Petrus…Now, maybe it’s just me, but I feel like when you say ’parody’ a lot of people will think Renaissance. I certainly do; often works based on Josquin out of adulation and fanboying! But here we’ve got this early Baroque example. Am I just wrong about this? Or was the idea of the parody mass really still going?

No, you’re totally right! There’s two things you have to remember about this, and one is that Rome was old-fashioned, and it was tradition. Whereas Venice was already moving onto the next thing by 1600 (partly because of plague; Florence, Venice, Mantua etc were all looking ahead), in Rome they were very happy with how everything was, thank you very much! And so their development of their music was different. For big feast-days they basically said ‘More of the same, please!’ - and ‘the same’ at the time was a three-choir mass instead of a normal one-choir or two-choir mass. So Benevoli’s thing was to do four-choir masses and although he wasn’t the only one because he was head of the Cappella Giulia, he knew all the best singers.

But sorry, back to your question: this is very much a Renaissance phenomenon. You did get Carissimi writing a L’homme armé mass in I think the 1640s or 50s, but generally you don’t, and this is entirely unlike a Renaissance composer’s take on it. A Renaissance composer will take the voice-leading and take a passage and you’ll hear it in the Kyrie or Gloria. Here, the Kyrie starts with the opening of Tu es Petrus, but then you don’t hear it again until the Agnus Dei! What Benevoli does is much more like Bach or even Beethoven: he takes one little bass part, from the opening of Tu es Petrus, and starts using that as a theme. So it’s much more hidden, much more what we would think of as a modern composition-based approach.

Clearly they had a high enough opinion of Palestrina to write a parody mass on Tu es Petrus, but Palestrina’s own Missa Tu es Petrus already exists! So if you venerate him that much, then why not just do that? It seems paradoxical…

I suppose because you must be seen to create something new, and even conservative Rome wanted to create new art. St Peter’s was finished in 1626, so they felt that they must have new music: it’s just that they wanted it to be similar!

Clearly Benevoli wanted to write something himself, and he was aware of the stile antico, but he had all these things buzzing around in his head. God knows what it would have sounded like in a place even as small as the Santa Maria Montesanto! We think of that as a small church, but it’s still built of stone - and although two of the organ lofts are quite close to each other, the other two are at the other end of this smallish church so it would still have been horrendous to get it together!

Florian Bassani has made the point that a basic skill of a singer in this kind of piece in the seventeenth century would have been not to listen to anything he could hear but simply to rely on his sub-conductor standing within a metre of him, because you couldn’t rely on what you heard. Now, I want musicians who can spark off each other, and who are making chamber music. Even with the singers as close as we had them on this recording there’s still a limit to which you can do that, but being fifteen metres away from the other group as it must’ve been in St Peter’s Rome…they must’ve been entirely unable to hear anything else going on! But they were clearly very good at it – when André Maugars visits in 1639 he’s astonished by the togetherness of it all. Also with the secondary choirs going down the nave with their separate pillars – they have the sub-conductors and they can keep it together, but I think of that French general watching the Charge of the Light Brigade in the Crimean War and saying ‘C’est magnifique, mais ce n’est pas la guerre!’.

They drilled this into us the first time I did Spem and I suppose it’s the same thing here…you just unlearn everything you’ve learned over the past however many years, and use your eyes rather than your ears. The effect must be great if you are in the exact focal point of all these sonic things, but surely anywhere else it’s going to sound lopsided?

Exactly, and I suppose the idea of having these secondary choirs – doubled-up versions of your one- or two-to-a-part main choirs – is so that everyone else in the nave could hear it.

So it’s essentially just a PA system?

That’s exactly what it is! If you’re back in the nave you won’t hear the A-choirs, you’ll only hear the B-choirs, so it’s not as if they’re creating a richer sound – it’s very much a PA system.

Is the arrangement of the choirs more linear than circular then, in this case?

The evidence is unclear. But certainly in St Peter’s or Montesanto you could have the choirs in a circle with the baldacchino (the canopy/altar) in the centre, and in the middle of that it would sound OK.

But yes, who was it really in time for? It’s a little bit like the idea behind the multi-choir music in Venice (although it’s a totally different style) in that it’s designed to impress – you’re trying to use music as a political power-gesture, to say ‘We can do this. Why would you only have three choirs when you could have four?’

I don’t know whether this is true of other albums and ensembles, but I noticed the sponsorship not just of individual tracks but of individual singers, which I thought was interesting: how long have you been doing that super-duper-focused kind of approach to fundraising?

I think we started with just tracks…I won’t go into the details of how much a disc costs, but it’s well into five figures – all that money has to be raised in advance, otherwise you can’t be sure of paying people. If you work out therefore what a track is, that means that each track is worth about £5k. Now I know plenty of enthusiastic people who are keen to help, but I don’t know very wealthy people.

So by splitting both the tracks and the individual performers, we allow people to be involved and take possession: they turn up to a rehearsal and think ‘That cornetto-player is only there because I’ve helped to sponsor their part’ . That gives people a sense of ownership, and they know that they’ve helped this recording happen.

The difficulty is that when you’ve asked once, it’s difficult to ask too soon again: we’ve just recorded the Victoria Tenebrae, and I mentioned it once in an email but I wasn’t going to follow that up because you just can’t constantly be asking the same people for money.

We do also rely on one or two sponsors that have given us substantial five-figure sums over the years to keep us going, otherwise we wouldn’t be here. The other thing (and please do print this!) is that post-COVID we now pay musicians even if they’re ill and aren’t able to do a concert. It’s absolutely iniquitous that if they’re ill or something happens to them that means they can’t be there, they’re then having to deal with that at the same time as not being paid! It doesn’t happen here in my job at the University of York: I have security if I’m ill.

I’ve now prioritised it, because it’s really hard out there. I see the student end: I teach undergrad and Masters students here, and we’re pushing people out into the world to do these jobs…They’re paying £1k a month in rent to live in London, and they have to be supported. It’s sort of a mindset thing: you just have to build it into your budget. And I think you have to keep it simple for a small organisation like ours.. No-one wants fifteen different levels of friendship: platinum, gold, silver…our entry-rate was £30 in 2006 when we started, and it’s still £30 now, because what we do is so niche (actually it’s massively not niche, it just appears to be!) that we just want people at least to know what we’re doing, and then it’s up to them whether they want to take any further interest…

It reminds me of years ago when somewhere (maybe the South Bank Centre) was getting a new organ, and you could sponsor a pipe: it went from one-foot flutes to a 32-foot reed. Obviously not everybody can afford to sponsor a massive pipe, so you’re lowering the bar for people who do want to be supportive but aren’t minted!

Exactly! Bricks in walls, seats in theatre etc…

As Pat Dunachie of The King’s Singers says, the days when they can focus solely on the music are gone: they’re mostly dealing with the admin. And that’s a top group. Artists should live in the real world, then they have something to say about the real world. You might think ‘Well, how is that related to Benevoli?’. Well, I’ll tell you why: there’s a moment where he sets ‘Et con glorificatur’ and all the voices have tricky very fast leads – difficult to get it together in a clear acoustic, let alone a church. Surely there is no way Benevoli ever thought that was going to sound together! We were in hysterics the first time we sang that and and just it’s one of a number of moments in this mass where it’s clear that Benevoli was just sending up the performers. There’s the ‘Non erit finis’ line for soprano which just goes on and on…now, I know that castratos had increased lung-capacity, but not that much! It reminds me of Mozart sending up the horn player Leutgeb. This music lives in the real world, and that’s why it’s still relevant now.

I Fagiolini, The City Musick, Robert Hollingworth

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

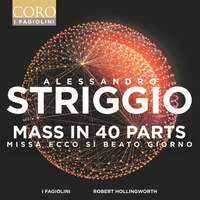

I Fagiolini, Robert Hollingworth

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC