Interview,

Delyana Lazarova on the music of Dobrinka Tabakova

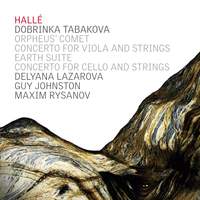

Bulgarian-British composer Dobrinka Tabakova's new album with the Hallé, featuring two concertos, her Earth Suite and the thrilling Orpheus' Comet, is not merely a major new addition to the contemporary orchestral repertoire on record - though it is certainly that, with Tabakova's musical language striking the balance between accessibility and experimentation, by turns lush and astringent. But it also captures a unique musical coincidence that brought her and fellow Bulgarian Delyana Lazarova together for the first time - having being brought up in the same city but, against all the odds, never previously met.

Lazarova has just completed a spell at the Hallé, combining the role of Assistant Conductor with directing the Hallé Youth Orchestra and working with Mark Elder, and conducts on this exciting new recording. I caught up with her recently to talk about Tabakova's music, her time at the Hallé, and the insights that her earlier career as a string player have brought to her conducting work.

Although you and Dobrinka were brought up in the same city, you hadn’t crossed paths until this project brought you together! As you got to know each other, did you find any “near misses” from earlier in your careers, where without knowing it you’d narrowly missed working together?

To be honest, I did know of her; I had heard her music before. When I moved to Manchester (which was actually in the middle of the pandemic, in September 2020) she was one of the first people who gave me a virtual welcome there; we grabbed a virtual glass of wine, connected and started talking about possibilities, and music, and all of that. Then we realised that we had quite a lot of common friends because we were not merely from the same city of Plovdiv but almost from the same neighbourhood! Probably we would have seen each other a few times as children, we just didn't know it. It was an amazing coincidence that we were in the UK at the same time and then things came together in this inspiring project.

You’ve just finished your term as the Hallé’s Assistant Conductor; what was the relationship like with the orchestra over that time?

For me it was a really special relationship, and it still is - after three years I've finished, but next season I'm coming back as a guest conductor. The contract had initially been for two years, but after the pandemic and everything intervened, we extended it. It was a really important time in my professional development. It's a special connection and I think it will always be; I really grew at the Hallé, not just as a musician and a conductor but as a person. Sir Mark Elder, the orchestra, the whole staff and administration - they all welcomed me with open arms and supported me during the whole period.

It was a perfect place for me to learn and grow - learning not only from Mark Elder, who is very knowledgeable and generous with his time, making sure that I understand his views, but also from the orchestra themselves. So many times I was able to conduct them, both in educational concerts and as part of our Opus series, and the feedback I had from them gave me such valuable information that I could take and bring to other places where I was guest conducting.

Whenever I come back to Manchester I do feel like I'm coming back home. It's my first musical home as a conductor.

So is there a strong 'mentoring' element to this sort of position? Were you more of a conductor in your own right, or more of a pupil/apprentice?

It's a mix. The unique position of Assistant Conductor and Music Director of the Hallé Youth Orchestra and assistant to Mark - it's really three jobs in one. You have to be the Music Director of the Youth Orchestra, working with these young musicians that are also growing in front of your eyes, and helping them develop and find musical languages for different pieces. Then you're also assisting Mark, which is a completely different thing; you have to always listen for balance in the hall, and at the same time there is the element of learning - rehearsal techniques, as well as discussing with him certain elements and challenges in the pieces we're working on. It's information straight 'from the kitchen', as it were - it's so valuable and you learn so much as a young conductor. Especially assisting an artist such Sir Mark Elder.

The third aspect was conducting all of the educational concerts and outreach projects, as well as some of the Opus series. In my last year it was wonderful - they gave me the opening and closing concerts of the season! And this recording, too - this was a high point of these three years for me.

How involved was Dobrinka herself in the process of preparing and recording these works?

For her as a composer I think it's very special, just as it is for me; usually, as a conductor, you don't have the chance to have the composer right next to you. It's such a luxury! If I have any questions or doubts about something, she can answer. And from the very first movement it felt as we both, and the soloists, all became a team. She was really involved, but there was a constant give-and-take, and brainstorming about how this particular part could develop, or how that particular movement might go, and things we could try out.

It also helped a lot that the orchestra really, really liked her music - so we were all on the same team, making sure that everything was becoming better and better each time. I think it's crucial for composers nowadays to be involved in the process of bringing their piece to life. I'm always open to hearing what the composer's perspective is on everything; I do have my reading on the score and my ideas, but it's a great luxury to be able to double-check if you're on the right path.

The notes accompanying this album refer to Dobrinka’s “desire not to be boxed into being one thing”. That being said, do you think there are elements of musical language that these four pieces share?

It's amazing, in a way - these pieces are all so different, and at the same time, there is something quite universal about them. My perspective on it is that each of them has a very strong narrative. All of these pieces are so easy to connect to - no matter if you are a classical music aficionado or you've just stumbled on them without having any background in classical music. Anyone can connect to them and attach their story to them, because they are tonal but at the same the combination of colours that she uses in the orchestra is unique. Some of them we really haven't heard before. But everything is mixed and put together in such a way that each piece takes you on a journey. And it's up to you to decide what exactly this journey is - that's the beautiful thing about music, after all, its abstract nature. Even if we have certain guidelines, with the names of the pieces, there's still so much room for us to really open our hearts, to listen, and to enter her world, which is really unique.

Rather than being named for their tempo markings as in many older classical works, the movements of the two concertos and the Earth Suite have subtitles evoking moods and inspirations. How easy is it to put these across in performance? How important is it to you that a given movement happens to be called 'Tectonic', for instance?

Of course it's important - you already have a picture in mind, but then the layers that come with that, of how the music develops, bring something completely different. In other words, I see the score as a map, but it's not the place. We can get to the place only by hearing and experiencing the music. For instance, 'Pacific' - immediately we think of certain images, but the calmness and the beautiful depth that Dobrinka achieves with the texture of the orchestra is something that I find really special.

Or let's take the absolutely stunning second movement of the cello concerto; it's so personal. I can't say exactly what its style is, but somehow when you hear it, you just know. In some ways, words really come short when describing these movements.

The words might be a kind of signpost, but once the music starts, you're on the way towards the actual place - seeing the colours and pictures, and experiencing the music. After all, that's the beauty of music; it's an art that develops in time. And it's only alive and able to be experienced while we're playing it. Dobrinka has put these indications in the music to put you into the right kind of world when you read them. We're talking about a different degree of depth from just 'Allegro' or 'Andante' - though, longer ago, those were ways of indicating moods as well. Happy, fast, or a bit more thoughtful. Dobrinka's descriptions immediately make the pieces more personal to the players - as well as, I hope, to the audience.

You’re a string player yourself - do you find that performing experience is useful when you’re conducting (whether just orchestral works or, indeed, string concertos)?

I was a violinist, yes - I studied in the US, at Indiana University. I did that for a long time, but I was always fascinated by the idea of conducting. Or not even conducting itself, but rather the idea of studying the scores and really understanding the musical language of this or that composer. And not only that, but the way they describe things in the music. Every composer has their own language; for example, an accent in Brahms has a completely different meaning to an accent in Stravinsky. Or Dvořák's different accents and sforzandi, and why he uses one here and another one there. So many things I was completely fascinated by.

Later on, after I'd been conducting for a while, I was accepted into the wonderful (and very sought-after) conducting class of Johannes Schlaefli in Zurich, and right after this I also won the Siemens Hallé Conducting Competition. So from there it was a clear path for me.

The experience as a violinist is very useful; I think it's almost my secret power! I've been on the other side as a player; I know how it feels. Also, as a string player in particular, I can speak their language and I know exactly what to ask them for. Immediately that creates a connection with whatever orchestra I'm working with. I feel lucky that my musical journey began as a violinist.

I've certainly encountered choral singers who say that singing for a conductor who is themselves a singer is infinitely better than singing for one who isn't!

Yes, of course. It's a wonderful thing about conducting, really - you are in effect a professional learner. You constantly have to learn things - so, yes, I'm a violinist and I know a lot about string players, but at the same time, learning how to think as a singer or a flautist or a pianist, for example, and how to be helpful to them, is important. We're speaking the same language but in a different dialect.

Certainly my past musical upbringing is a big plus for me right now.

Maxim Rysanov (viola), Guy Johnston (cello), Hallé Orchestra, Delyana Lazarova

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC