Interview,

John Andrews on Ethel Smyth's Der Wald

In the run-up to the release of the recording, I spoke to John about the work's early reception and performance-history, Smyth's gift for conjuring a vivid sense of place and atmosphere, how the musical language here differs from the more expansive sound-world of her next opera The Wreckers - and his conviction that 'there’s a much more vibrant and continuous tradition of English serious opera than we ever give ourselves credit for'...

Dvořák's Rusalka was the first piece that sprang to mind when I began listening to this opera, but it then develops in all manner of directions...did any other nineteenth-century works come to mind for you when you began working on it?

If you read of the criticism of the time, it gives you quite a strong impression of what it was perceived to be like - or perhaps more importantly what it was not like! - but then you hear this really individual voice, and realise that they’re almost all entirely misleading.

The sound-world is obviously very familiar: it’s not going to frighten anyone who enjoys Mendelssohn, Brahms, Tchaikovsky and indeed Dvořák. There’s Rusalka in there certainly, but listening back to the edits I was more and more aware of the similarity to his tone-poems based on Czech fairy-tales: The Golden Spinning Wheel, The Noon Witch and The Water Goblin. It’s rooted in exactly that world, where you start somewhere very domestic and familiar - in villages with folk-singing and dances – giving way first to something lush and Romantic, but the deeper you go into the fairy-tale the weirder it gets…

Hänsel und Gretel also kept coming to mind as we worked on the piece: that was a work which Smyth certainly knew later in life, although whether she could have heard it at this point isn’t clear. It was premiered a decade earlier, but in a world without recordings that’s no guarantee…

How much do we know about which composers influenced her directly in this piece?

Again it’s difficult to be certain about direct influences, because she was so well-connected and immersed in the European musical world. We know that she knew Brahms and Tchaikovsky (who was important in encouraging her) - and also that she was persuaded in the direction of opera by Hermann Levi, who was Wagner’s second-in-command and had conducted the first performance of Parsifal.

Critics at the time talked a lot about 'Wagnerism' in this score, but I’m not so sure… There’s the love-potion scene with horn solo and harp which is surely a nod to Tristan und Isolde, but otherwise she’s no more Wagnerian than anybody else writing at that time. The Proms were programming wall-to-wall Wagner every season: it was very much in vogue, so you’d be hard-pressed to escape it entirely! What there is though is a real sense of the Forest as a character which creates its own, unquestionably Germanic, sound-world.

'Wagnerism' was probably also a nod to the use of any kind of leitmotif: but while Smyth’s characters do have their themes (such as the descending chromatic motif for Iolanthe) it’s not anything like as integral to the score as it is for Wagner. So you can see why people would’ve made those comparisons at the time, but for a modern audience it’s not really helpful.

What about composers closer to home? Is it pure coincidence that one of the main characters is called Iolanthe, or is it possible that she knew Sullivan's operetta of the same name?

I don’t think so! But it’s interesting that Sullivan and Smyth do both quote Mendelssohn’s woodwind chords at the opening to the Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture. Those chords are referenced at the opening of Sullivan’s Overture, and are very similar to the ones setting the scene in the forest right after the Prelude of Der Wald. That may not be a deliberate homage on Smyth’s part, but it’s certainly there on a subconscious level. As I say, the Forest is a character and seems to be referencing its own musical heritage.

For me, that link is particularly strong as this project actually came out of my discovery of Sullivan’s work beyond the Savoy Operas. It was getting to know his serious output which made me realise that there was this whole corpus of English opera which doesn’t often see the light of day. If we want to trace my interest even further back, it starts with my doctorate on Handel and his English contemporaries, which led to me discovering people like Eccles, Lampe and Arne - all those composers whose reputations were high at the time but haven’t necessarily survived for posterity. That in turn fed into my work on Sullivan’s oratorios and serious theatre works, and the realisation that there’s a much more vibrant and continuous tradition of English serious opera than we ever give ourselves credit for.

So how did that line of enquiry lead you to Der Wald?

A few years ago I was researching the major contributions to that English-language tradition, and this one came up; I sent off to Boosey & Hawkes for a perusal copy and thought it would be marvellous to do one day. Like so many of these things it went into the back pocket for a while; we came very close to doing a concert-performance with one of the summer opera-companies in the UK a couple of years ago, but that fell victim to COVID in terms of funding.

Around the same time, I was talking to the BBC about a potential Malcolm Sargent disc with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, because I’ve got some of his early works that have never been recorded and various things which he wrote and arranged for the Proms. COVID made that a very complicated proposition as it involves a big chorus, but sitting on my desk was this perfect alternative.

Do you see the piece as a chamber-opera, or as something rather grander?

In terms of the dramatic storytelling it’s really quite intimate: the core of it is a series of scenes with a just couple of people on stage. The orchestra isn’t enormous – triple wind and normal brass – but Smyth uses the cor anglais, viola and bass clarinet incredibly well to create those forest sounds: there is really beautiful, individual orchestration in those passages. But when she does use everything, it’s an overpowering force of texture, and there is real visceral violence at the climax.

And she asks an astonishing amount from the singers. Iolanthe is listed as a soprano or mezzo role in the score, but she has numerous top Bs: and although Smyth does offer lower options, Claire went for the full dramatic range! She and Natalya ate those roles for breakfast, and you can hear every word: somehow in amongst all those vaulting melodic lines and shifts in register you’ve also got to be able to follow the text, and they did an incredible job.

Smyth seems to have moved in quite a different direction for her next opera, The Wreckers...do you see any kinship between the two works?

I think it is a different sound-world: there are tonal similarities, and you can hear her use of characteristic harmonic steps in both works, but this doesn’t have the expansiveness of The Wreckers: Der Wald is almost claustrophobic in its intensity. There’s really nothing spare in this score: it drives on relentlessly, and I do think that forest setting draws on a whole Central European sound-world that’s familiar to a lot of us from composers like Dvořák and Smetana.

I think we’ve developed quite hard-wired associations for those sounds and the way that they’re linked to places: in the libretto Smyth says that this could take place in any medieval country, but to me the score itself definitely places us in Central Europe.

It seems quite extraordinary that the piece disappeared almost entirely from the repertoire after its warm reception at Covent Garden and subsequent production at the Metropolitan Opera - what happened?

Some of the reviews from the Met premiere in 1902 are really rather poisonous, dripping with misogynist, homophobic and anti-British sentiment: they didn’t like that she was a woman, they didn’t like that she was English, or worse that she was socially connected to the New York plutocracy. Add in the fact that she was a gay woman and you get a lot of hostility from critics, although that clearly wasn’t felt by audiences as a whole, as even the most negative reviews had to concede.

I think it would’ve needed her to fight for longer, and she felt there were more important battles that needed her attention. But even so, the neglect is extraordinary. This question crops up a lot with forgotten composers, and the thing to remember is that for such a long time the natural thing was for a piece to die after a couple of seasons: it was true for Mozart, it was true for Donizetti, and even up to Verdi’s time composers wrote for that season and didn’t necessarily expect a piece to have a long life.

The revolution in printing in the nineteenth century and then the advent of recordings made it possible for pieces to survive, but it was still contingent on someone from a generation or two afterwards flying the flag for them: when a composer passed there was usually a period of complete forgetfulness, and then eventually somebody would take up the cause …

And I think that’s what Smyth lacked: somebody to fight for her as a composer a generation later. Despite those hostile reviews, I don’t think there was any active suppression: there was a lot of very good music written in the first half of the twentieth century which has been left behind simply for want of a dedicated champion.

Britten was very wise in setting up Snape Maltings just as Wagner had set up Bayreuth; Elgar had the Three Choirs Festival and the Birmingham Festival, and Sullivan had the D’Oyly Carte, which almost became a poisoned chalice for him. And certain composers were championed by former students - Mahler had Klemperer and Walter, who in turn passed that torch onto Bernstein and his generation. If there weren’t institutions created to keep your name alive, then it would struggle to stay in the public consciousness.

Might we see a fully-staged production any time soon, and if so then what would you pair with it?

I would hope so. It’s incredibly stageable and lasts barely over an hour, so the potential for an interesting double-bill is there. Something like Pagliacci or Cavalleria rusticana would probably be overpowering, but I think any of the Trittico operas would work well. Or perhaps one of the quirkier twentieth-century operas would make a nice contrast: Maconchy’s The Sofa, Walton’s The Bear, or Ravel’s L’heure Espagnol…

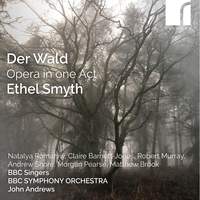

Natalya Romaniw (Röschen), Claire Barnett-Jones (Iolanthe), Robert Murray (Heinrich), Andrew Shore (A Peddler), Morgan Pearse (Count Rudolf), Matthew Brook (Peter)

BBC Symphony Orchestra, BBC Singers, John Andrews

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC, Hi-Res+ FLAC