Interview,

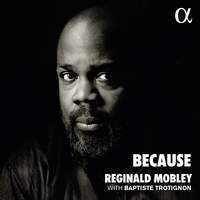

Reginald Mobley on Because

Ahead of their Proms performance of the programme at Gateshead's The Sage this weekend, Reggie spoke to me about the role which spirituals have played in his personal and musical journey, his shifting feelings about the treatment of this music by non-Black composers and performers, how his musical partnership with Trotignon began as a 'blind date' set up by their record-label - and his deeply-held conviction that music 'has an innate ability to create a space for growth and conversation'...

Has this music always been a part of your life?

It seems like every Black queer countertenor has the same origin-story: we all sprung up in the South, and before our age was in double-digits we were singing gospel and spirituals in our local church choir. My mother and grandmother sang these songs around the house, so they were the soundtrack of my childhood - even the songs that began my understanding of music altogether. At four or five years old, you don’t really know about the history of spirituals and the pain and heartache and trauma of slavery: you just pick up these beautiful melodies and sense that they’re somehow a part of who you are. But those of us who grew up in the South are still dealing with the repercussions of slavery today - probably even more now than we have in the past thanks to a couple of recent elections…

And the power of this music has remained consistent: it serves the same role for me and my family facing issues in the South that it served 400 years ago. This music still has a practical purpose – it’s a device that helps us to find our way through life and its difficulties. It created a foundation for not just who I am as a musician, but who I am as a Black person, as a human being.

At what stage did you decide to pursue a career in music?

My path involved a lot of stumbling around corners into people who heard and encouraged me, and I’m very grateful for that. I stopped singing in my church choir once my voice started changing, and for a long time music was just something that I enjoyed at home. In the US we have something called magnet schools, which are public schools that focus on specific disciplines, and my school was a magnet for drafting and architecture. I had a part-time job with a graphic art company in my hometown, and I was all set to pursue a career as an architect or something in the visual arts. Then in middle school I picked up a trumpet and eventually found myself playing a Bach fugue with my school concert band, and that put me back on the correct path…

The real turning-point happened near the end of high school, when a teacher heard me singing in the corridor and had me join the chorus for my last year. At the last minute I changed course completely: even though I had a scholarship for art I was able to get that scholarship matched at a different school for music. I didn’t even take the trumpet!.

Did you ever pick it up again?!

I took it up again for a short while in college, when I wanted to join the basketball band because I had a huge crush on one of the players! Since then I haven’t played much, but I recently got a cornetto so I’m going to get back into it with some early brass-playing. I honestly think that a path was set for me in that I’ve lived my entire life without fully-functioning lungs: I’ve had pretty bad asthma since birth, and playing trumpet helped me to understand and even my breath-flow. It was ideal training to become a singer, almost as if all the different strands in my life have pulled together to counter the difficulties I’ve faced.

Did you always sing as a countertenor?

I was 17 when I started singing seriously, and at that point I was really a baritone with a high extension. It was only when I moved back to Florida a few years later that my voice-teacher heard me singing on the top line of a barbershop quartet and pulled me into his office to sing in that register. He told me that I was a countertenor and I remember saying ‘Oh, fantastic…but what’s a countertenor?!’ He gave me a pile of CDs to listen to over the weekend and said: ‘When you come back to your lesson next week, this is what you’ll be doing for the rest of your life’. And I haven’t proved him wrong yet!

Which Black classical singers particularly inspired you in spirituals?

Because I got into classical singing relatively late, it was years before I heard that famous album with Jessye Norman and Kathleen Battle: I’d never heard Black singers in this industry, let alone singing our own music in a ‘classical’ context. It was only after I started singing as a countertenor that I discovered Derek Lee Ragin, who did a couple of recordings with John Eliot Gardiner as well as being one half of the voice of Farinelli in the 1994 film!

Your Grammy-nominated album American Originals was a timely reminder that Black voices were already making vital contributions to classical music several centuries ago…

American Originals and Because are two sides of the same coin. At the beginning of 2020 I had a concert in Arizona with Agave Baroque, and that was when the American Originals project began. We came together again in August after the murder of George Floyd and there seemed to be a need to speak out on behalf of diversity and equality; because everything was locked down by that point, a recording seemed to be the best way to do that.

The idea was to assemble a programme of music from the Americas where not one single composer is white, highlighting the fact that people of colour existed in the Western classical tradition long before most people think. We tend to assume that it all started with people like Harry Burleigh and William Grant Still – but the reality is that in the eighteenth century there was Ignatius Sancho in England, there was Chevalier Saint-Georges in Paris, there was the Afro-Cuban Baroque composer Esteban Salas…

I thought it was important to show that people that looked like me did work our way into a style or tradition that was already there, but also that we were very much an active part of its development. We always had a seat at the table: it’s just that someone else has usually been sitting in it! So this project was me doing my part to counteract the ideas I grew up with, where classical music was this white elite art-form where I was not welcome, and it does seem to have resonated with people: for my first solo album with a known independent label to get a Grammy nomination was really nice!

How did you meet Baptiste Trotignon, your partner on Because?

American Originals was recorded in August 2020, and the foundations for Because were laid shortly afterwards when Didier Martin (the head of Alpha Classics) called me to discuss my first recording on the label. Initially I thought he was going to cancel because of COVID, but actually he said ‘I want to try partnering you with this jazz pianist that I know, just to see what would happen…’.

Baptiste comes to classical music as a jazz pianist, whereas I’m a classical artist who can also do jazz. And through working on this project we were able to come to a place where a modern white jazz pianist could explore the foundations of what he does and where it comes from. You see how slave songs and spirituals (which are truly 'Early Music') are also a well-spring of sources which has influenced so much music that we know now. It’s through jazz and spirituals and through people like Florence Price and Harry Burleigh that you see the significance of what was created in the American South: this thing that stupefied Dvořák and Delius and MacDowell, that Stravinsky fell in love with.

How do you feel about white composers and performers appropriating spirituals, for instance in works like Tippett’s A Child of Our Time?

This is an issue that I’ve evolved along with, and it’s an issue that ebbs and flows within the Black American community as well. When I first heard A Child of Our Time, I don’t think I was very welcoming to the use of spirituals in that way. I thought it was a beautiful piece and it was interesting to see Tippett using them in the way Bach would use chorales in his Passions, but something in me recoiled at hearing the music of my tradition as done through the hands of a non-American white composer. And the main reason for that reaction is still an issue now: even in 2023 our music (and the music that evolved through our music) is welcomed through the doors of every concert-hall and theatre, but in spaces where people of colour are still made to feel uncomfortable and unwelcome.

But now I’ve matured in my thinking on that - music is something that can’t be owned. Regardless of whether you have faith in God (which I do) or believe in something greater than we can explain, there is a practical magic here: there’s something about music that has an innate power to change people, in a moment. Strip away everything you know about different musical styles and languages, and you see that what’s really behind it all is emotion. I feel love and hate and anger - and so did Bach, so did my ancestors, so will our children. And when this music has the ability to create a space for growth and conversation, I think it’s an absolute loss to try and keep it from being shared.

So going back to music of my tradition being used by people like Tippett, I say keep going! I think people should explore these incredible melodies in the same way that Vaughan Williams and Britten explored the music of Tallis and Purcell, the same way that Respighi and Shostakovich and Elgar expanded four-part fugues by Bach into incredible orchestral arrangements. I think there’s so much exploration that can really connect us to each other if we just allow it, but that also involves being willing to question why certain things haven’t happened yet and why the overall pace is so slow.

How do we start those conversations?

During the pandemic I was doing a lot of consulting work with all-white choral societies in places like Nebraska, and one question I got asked a lot was ‘Is it OK for us to sing spirituals?’. I’m not here to give you permission or absolve you from any guilt that you should or shouldn’t have: what I am saying is that if this music moves you then why shouldn’t you share it? But do take the opportunity to have a conversation about why your choir’s all-white – and why orchestras, ensembles, even artistic planning boards and committees across the industry are still so devoid of diversity.

Tell me a little about your non-musical activism…

It’s something that I’m trying to expand, not just in the States but also here in the UK. Over the next year I’ll be wrapping up some projects with the AHRC, where I’ve been visiting various libraries, museums and galleries as well as houses that are under the purview of the National Trust: my mission is to get some exposure for stories that need to be told and cultural treasure that should be given some kind of light and awareness.

Will Sunday’s Prom at the Sage be your first visit to Tyneside?

Baptiste and I piloted a concert-version of the album at Newcastle University at the end of the lockdown, which was my first time performing in front of an audience since COVID hit. It was warmly received and I felt very welcome: walking through the university and seeing that statue of Martin Luther King was so awesome. I was back on Tyneside recently with the Monteverdi Choir, too: we started John Eliot’s eightieth-birthday tour with Bach’s Mass in B minor at Sage One in April. Baptiste and I will be performing the full album on Sunday, and there might be a couple of surprises as well…!

Reginald Mobley and Baptiste Trotignon's BBC Prom at The Sage takes place this Sunday at 2pm, and will be broadcast live on Radio 3.

Reginald Mobley (countertenor), Baptiste Trotignon (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Featuring music by Esteban Salas y Castro, Florence Beatrice Price, José Mauricio Nuñes Garcia, Scott Joplin, Justin Holland and Manuel de Zumaya, the album was nominated for a Grammy last year and was praised in Gramophone for 'Mobley’s wonderfully rich voice, with its seamless high end and irresistible sense of narrative flow'.