Russian song is quite unusual territory for a countertenor! Why did you choose to focus on this area for your debut recording?

The first thing I thought to myself, was “We don’t need another recording of Bach cantatas from a countertenor!” There seemed to be a period whilst I was a student when every single one of us was producing one of those or a Vivaldi / Pergolesi Stabat Mater as a sort of rite of passage, and I do understand why that happens. At the start of your career you’re more likely to be worried about what the purists are going to say, and that was a time for recorded media, when it was commercially attractive to bring out the ‘definitive’ version of whatever. However, I’d like to think I’m established enough now to step outside the box for my debut album.

Part of the reason why I’m doing a Romantic album in the first place is to show that countertenors didn’t just disappear for a hundred years during the nineteenth century – we were there all along, and we weren’t just singing in church! When I was doing my Early Music Masters at Guildhall I discovered that there were so many different fachs beyond the main five that we think of now, and between contralto and tenor, I found there were two extra things that I’d never com across: a very high tenor called a contraltino and also the contraltisto which Bellini used for trouser-roles.

Rossini hated the fashion for tenors to push up their stentorian chest-voice: he always wanted the high Cs to be falsetto, but the public lapped it up. So perhaps it was simply fashion which worked the countertenors out of their fach in opera throughout the nineteenth century. If the contraltisti were neither tenors, nor female contraltos, then the strong suggestion is that countertenors were there all along, hiding in plain sight; You could say it is the opposite of “gone but not forgotten!”

When did you begin exploring this repertoire?

It actually started when I was still studying: I felt resistance with French mélodie and Lieder from some of my coaches, but nobody seemed to worry about a countertenor singing Russian repertoire. It seems to be an open playing-field, and I think part of that is because of the enormous amount of pride in the repertoire itself – people will celebrate anyone who champions it. My Russian coach at the beginning was the fabulous Czech force of nature that is Lada Valešová, who’s now quite a renowned conductor: at our first session she just said ‘Darling, just sing like this and you sound Russian, it’s great!’. So off we went…

And that’s been the response pretty much across the board. Every time I’ve had an opera contract in Germany or Holland there’s always been a Russian singer in the ensemble – usually someone whose voice is obviously too light to sing the Boris Godunovs etc which they would do at home, and who’s found themselves a Fest contract doing Mozart or even Monteverdi. I’d grab them and ask them to come into the studio and give me a bit of coaching, and even though some of them were a bit surprised to come across a countertenor who wanted to sing Russian repertoire the verdict was always positive!

Making the case for the countertenor as a Romantic instrument marks a considerable technical development. How did this happen for you and which established singers inspired you in this music?

I always thought that Baroque music would be the mainstay of my career as a principal artist – every Handel opera has a second countertenor role, and that’s a perfect way to learn the ropes. But it just didn’t happen that way for me. Instead I was thrown lots of contemporary music and world premieres, and that got my foot in the door at the big houses – it even got me a title-role on the main stage at Covent Garden!

The upshot was that instead of being surrounded by what promoters considered to be the ‘right’ Baroque voices, I was working alongside people like John Tomlinson and Thomas Allen: big, standard household names who make you really raise your game! I felt like I should be giving as much as everyone else on stage; developing the same sort of colour-palette, and it was working on this Romance repertoire that made me realise how to embrace that.

I sing these songs in exactly the same way that a full-blooded baritone would; Hvorostovsky is almost a ‘one-stop shop’ for anyone wanting to do some listening research, it’s just the range that’s different. Navigating the technical challenges, however, actually helped me find new colours and revelations in the text – there’s one song on the album ('Invocation' by Nicolai Medtner) which presents the countertenor with the opportunity to go down into the modal broken voice on the text “lunar light slides over gravestones”; this involves difficult slides in and out of bass to countertenor again, but what a way to highlight the otherworldliness of the text!

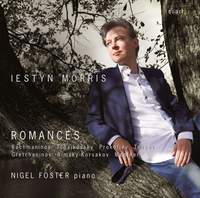

In this way it’s great to feel that you’re actually making the case for the voice-type as well as promoting this repertoire, because a lot of people won’t have heard it before. The idea is about bringing something new to an established tradition, which is sort of where the front cover came from: I thought that having a colour photo of me on a black-and-white background conveyed that quite nicely.

Is there much precedent for singers of your voice-type programming this music in recitals, and have concert-promoters been on board with the idea since you started offering it yourself?

I heard Lawrence Zazzo doing some Mussorgsky songs at Wigmore Hall a few years ago, but that was just a little sequence at the end of a recital - which is something I’ve done a lot myself out of necessity! So often I’d be invited to do a song-recital and get excited about bringing Romantic repertoire, only for the promoters to say ‘Actually, can you please do some Dowland?’. Then as an encore I’d do something Russian just to mix things up…

The main point, I suppose, is that whilst it is not unheard of for a countertenor to bring out some Romance in recital, it has never translated into a recording and I have not seen a countertenor included in a recital series of this music. I feel the voice-type has something to say and shouldn’t be excluded as being outside the ‘main’ voice-types. Something had to be done literally to bring the voice to the table and join the conversation, which was one of the driving forces behind this album project.

Did you need to transpose or adapt any of the songs to make them sit comfortably in your voice?

There are some world premiere recordings on the album, but in his 150th year, the bulk of it is Rachmaninov which should be reasonably well-known. Most of his songs have been recorded by famous baritones and mezzos, which was handy for me because I’d just find something in the bass, contralto or mezzo key and it would work in my voice - for the majority of the programme (just) I didn’t have to transpose at all. With my teaching hat on, I’d encourage any young countertenors who are interested in exploring this repertoire to do the same: the Rachmaninov songs in particular are very approachable, and you can just grab something off the shelf and have a go!

The Prokofiev songs in particular are really stunning, and were new to me - how did you come across them?

I was drawn to Prokofiev because the Oleg Prokofiev Trust was one of the major funders of the project, and the Op. 104 folk-songs became one of the gems of the programme because they give such counterpoint to all the larger, expansive Romantic stuff. The surprising thing is that most of them are actually very well-known folk melodies: they’re really the equivalent of the Britten folk-songs, which were published at almost exactly the same time (in 1944). Prokofiev really made stunning, absolutely valid art-songs out of these folk melodies, with his inimitable economy of accompaniment – ‘Dream’ is perhaps the most perfect example, but all of them are little jewels.

What was new to me is that Russian folk-songs are nearly always gender-specific – all of the songs on the album were intended to be sung by women. It generally seems to be the men’s lot to be called off to go to war or make a living elsewhere, so all of the male songs are full of nostalgia and longing for home rather than for a loved one. Conversely, the women are usually singing about their man who’s far away or about how terrible their life is now they’re stuck at home…there’s a lot of waiting going on, and those were exactly the kind of stories I was drawn to during lockdown.

The composer’s grandson Gabriel (who’s a fine electronic composer himself) was keen to let me know that it was common practice to just change the text, so I had his kind permission to tweak things so that these stories could grammatically come from a male perspective. That was quite fun: there’s one song in particular called ‘Katerina’, where the woman’s friend comes along and says ‘Stop worrying about your life and come for a walk with me!’. Having a male companion doing that brings a completely different perspective…

How did the recording itself come together, and where was it made?

I knew I had to present a valid alternative to the various other interpretations available, and part of that was looking into how the benchmark recordings of these songs were made: researching the sound-formats, the venue, that kind of thing. I think everyone in the classical recording world understands how important it is to have a space that faithfully represents the live experience – I’ve tried studio recordings and it really doesn’t suit my voice, because I’m so used to using the room itself to create resonance rather than singing in a dead studio.

I decided it would be nice to record on home-turf, and I was fortunate enough to get access to the Menuhin Hall in Surrey: it was just the right time because it was the school holidays so the hall was free, and they were just beginning to hire it out as a recording-space. I felt at home because I was on stage in a decent-sized concert-hall: every time I’ve heard Dmitri Hvorostovsky or Anna Netrebko doing Russian songs they’ve always been in halls which are the size of the Concertgebouw (if not bigger!), and that makes sense because engaging with this music should be a visceral experience.

I was exploring a lot of these songs in lockdown, so I did what so many others did and organised a livestream festival: for the four weeks before the recording I streamed fifteen-minute mini-recitals from the venue. I had the hall for two hours every Thursday, turned up with an HD camera, stereo mic, and took it from there: the confidence to do that was born out of necessity (lockdown had cleared my diary of preparatory recitals), but I needed that experience of being live (even in an empty space) and testing the repertoire properly. It turned out to be a really good format, because we ended up grouping all the songs thematically rather than by composer; I feel like we’re returning to the idea of a programmatic album that you’ll ideally want to listen to in one sitting.

If I’m expecting criticism I think it’s going to come from purists about the countertenor voice who don’t like it to sound so wild, rather than purists about Romance repertoire thinking ‘This voice has no place here’. But hopefully the two worlds will come together – the countertenor fans will hear different colours in the voice, and the Romantic listeners will find something new in repertoire which they think is familiar.