Interview,

Anna Bonitatibus on Monologues

In between her award-winning performances of Handel's Serse in Halle last month, Anna spoke to me about her fascination with this 'middle ground' between opera and song, how composers have used the stand-alone monologue to experiment with ideas which they later developed in their stage-works, and her special affinity with Joan of Arc and Mary Stuart as portrayed by Rossini and Wagner respectively...

What was the starting-point for the project?

I’ve always been very interested in this unclassifiable area of vocal music that runs in parallel to opera - pieces that occupy a terra di mezzo between opera and art-song without being either of them. From Monteverdi’s Lettera Amorosa onwards, there’s this rich tradition of works with a strong dramatic structure and a single, fully-realised character (usually from history or myth) with a compelling story to tell.

These works often get overshadowed by symphonic music and opera, which is such a pity: they can be easily performed without such a massive employment of resources, and they’ve also been an important experimentation-ground for composers who are better known for their operas. I was also fascinated by the idea of looking at these women from mythology and history with our modern sensibilities, and showing how very close they still are to us today.

My starting-point in terms of repertoire was Rossini’s Giovanna d’Arco, which is a work I’ve performed and loved for decades - I’ve always thought that this extraordinary piece didn’t just materialise out of nowhere! I’d sung quite a lot of cantatas by Vivaldi and Handel over the years and those are part of the story, but I felt that there were probably other pieces of the puzzle out there…

Especially in the current economic climate, I’m firmly convinced that the purpose of making a recording is to give a voice to underappreciated composers and repertoire: we have literally hundreds of recordings of (for instance) the Beethoven symphonies by the best performers imaginable, so our job is to shine a light into the dark corners.

And Nicola Zingarelli, who opens proceedings on the album, is a figure who could certainly use a little more illumination!

Zingarelli was an interesting case, because he’s always been perceived as a very serious and respected maestro di musica who was quite conservative in his musical tastes: he didn’t like Rossini when he arrived in Napoli, because he saw him as a contemporary composer with all sorts of radical new musical ideas. But this monologue Ero shows us another side of him altogether; it’s indebted to Haydn’s Arianna a Naxos in a way, I think, but he takes Haydn’s ideas and expands them in new directions.

Ero is a huge piece (over twenty minutes long), and if you look at the autograph score you see something extremely surprising: Zingarelli actually provided stage-directions. For every change of tempo you have a new idea: he writes text describing the rocks, the type of weeds and rushes, the light…and more importantly, the state of mind of the protagonist! He specifies it all in the score, just as Wagner did with his Ring Cycle – but Zingarelli did this in 1804! So much for him being an old-fashioned composer who was stuck in the past…

Rossini’s Giovanna d’Arco is probably the best-known work on the album - but even so, recordings aren’t exactly thick on the ground! What’s special about the piece for you?

Rossini has been so much part of my operatic career, and this particular piece has been with me for so long - but it’s extremely demanding, and I really wanted to record it now, with a deeper knowledge and experience on Rossini serio, compared to my beginnings. My pianist and I approach it in a totally new light, removing all of the rubbish that we singers plaster all over Rossini’s music and getting back to what he actually wrote - respecting tempi, agogica, expression-signs and everything else.

There are two important points that singers often ignore here: they insert pauses where Rossini didn’t write them, and they ornament upwards at the end of the piece where he writes descending scales…He wrote those scales for a specific dramatic reason, and that reason is that Giovanna is about to die - the woman burned, for goodness’ sake! Rossini tried to describe the entire parabola of her experience in eighteen minutes, and to simply treat it as a showpiece for mezzo and pianoforte disrespects both of them.

Do you think it’s obvious that this piece was written quite late in his career?

Yes: there’s a lot of uncertainty about the exact date of composition/first performance (despite Rossini writing '1832' in the autograph), but he’s already moving away from bel canto style and trying to do something different. Of course it contains a lot of elements of the previous Rossini but there’s also a new dramatic way of doing coloratura, which I think looks forward to Verdi. And I know this is a controversial opinion, but I don’t think of Rossini as a pure opera buffa composer - never, ever! Even in something as early as L’Italiana in Algeri, which is ostensibly a comic opera, he writes ‘Pensa alla patria’ for his heroine Isabella – an eight-minute, feminist monologue where she’s commanding the soldiers like a warrior-queen…What on earth is buffo about that?!

Moving forward a couple of decades, I never expected to hear you sing any Wagner! You mentioned that some composers had used stand-alone monologues to workshop ideas that subsequently found their way into operas - is that the case with Les Adieux de Marie Stuart?

Ha, this is officially my second Wagner assignment! Last year I performed the Wesendonck-Lieder for the first time, in a version with texts by Arrigo Boito which hardly anybody knows about. They sound completely different from the original, but they’re very beautiful and were approved by Wagner himself. I hope to bring them to London at some point…

Les Adieux de Marie Stuart is a very early piece: it was written shortly after Wagner arrived in Paris, and I thought it would be interesting for people to see what he was producing during those years when he was struggling to integrate into a society which seemed quite strange and alien to him.

It's a very challenging sing, even transposed into a key that works for me. In all honesty I don’t think writing for voices was ever Wagner’s best skill - and at this stage he was very much searching for his own style, so there’s a lot of Donizetti-esque coloratura as well as some much more dramatic writing. I approached it very calmly, and without pushing my voice beyond its comfort-zone: I think people often forget that Wagner belongs to the nineteenth century, not later! (Remember he actually died before Verdi, and not all that long after Rossini…).

It was a wonderful and very emotional experience, learning this piece: these words were apparently actually spoken by Mary Stuart, and I felt her voice (a very well-educated voice) more strongly than Wagner’s! It paints such a strong picture that I felt I could see the waves and the French coast gradually disappearing as she heads off to what we now know was a tragic destiny…

And how does the tradition of the female dramatic monologue develop in the twentieth century?

Respighi does something quite surprising in his Shelley setting Aretusa (1911): instead of writing something self-consciously ‘modern’, he looks to the past for inspiration and security. It was very fashionable to blend the new and the old like this at the beginning of the twentieth century – Busoni did the same, as did Stravinsky a bit later on. And then Poulenc took the idea of the one-woman show to new heights altogether with La dame de Monte Carlo and of course La voix humaine, which I’d have loved to include here if the programme hadn’t already been full to bursting!

Did you come across any equivalent pieces for male voice in the course of your research?

There are a few, but nowhere near as many as there are for the ladies. One extraordinary example which we’ve recently published is Donizetti’s enormous cantata Il Conte Ugolino, written for the bass Luigi Lablanche who was very famous at the time, and based on a passage in Dante’s Inferno. Ugolino is starving in Hell and at this point he’s ready to eat his own children: it’s terrifying stuff, and Donizetti does a wonderful job of letting us understand the state of mind of the protagonist.

But in general it seems that women were much more free to express emotions like desperation, love and rage in monologues - and the one piece by a woman on the album is so angry! I don’t know for sure if Pauline Viardot wrote the Scène d’Hermione for herself, but it’s possible: the vocal range makes sense and she’d certainly have been capable of playing the piano part, which is very intense but not that technically difficult.

There is a project underway in France to publish Viardot’s complete compositions for voice and piano, and the Bibliothèque nationale de France just made nearly all of her autograph manuscripts available online. It’s a bit difficult to read her writing, but what you do see is that she would produce many drafts of the same piece or idea, and a lot of them centred on famous female figures from history and myth. She was very into the topic.

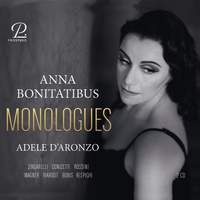

What’s the story behind that very cinematic cover-photo?

There’s something so cinematic about all of these monologues, and so many of the women put me in mind of [Italian actress] Anna Magnani: she was more dramatic than classically beautiful, but somehow she becomes beautiful because she’s dramatic! I asked the wonderful make-up artist Sabina Dinguelberg to recreate her look for the album-cover, and my favourite photographer Frank Bonitatibus to create the photographs. These monologues fit so well with this black and-white aesthetic from the 50s, from the after-war period – and as we all emerged from the pandemic I had this uncanny feeling that we were somehow living through that time all over again…

Anna Bonitatibus (mezzo), Adele d'Aronzo (piano)

Available Formats: 2 CDs, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

You can browse the completely available Consonarte catalogue (which includes new editions of Donizetti's Saffo and Zingarelli's Ero) over on our sheet-music site.