Interview,

Mary Bevan on Visions Illuminées

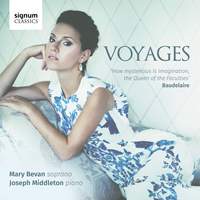

Having enormously enjoyed Mary Bevan and Joseph Middleton's Voyages (a predominantly French programme with a smattering of Schubert) a couple of years ago, I was intrigued to learn before Christmas that the British soprano was to release a supersized sequel of sorts in collaboration with 12 Ensemble and the Ruisi Quartet. Centring on Britten's Les Illuminations, the new album Visions Illuminées (out now on Signum) also includes a number of world premiere recordings: namely songs by Debussy and Ravel in new arrangements by Robin Holloway, and Augusta Holmès and Emmanuel Chabrier's chamber versions of their own Sérénades and 'Tes yeux bleus' respectively.

Shortly before the album's release, we met up for coffee in London to talk about Mary's ever-evolving relationship with Les Illuminations, how the rest of the programme came together (a process which included an extremely niche rescue-mission to Paris!) - and why she has no aspirations to follow in the footsteps of Barbara Hannigan and embark on a parallel career as a conductor...

Photo credit: Andrew Staples.

The mainstay of the programme is Britten's Les Illuminations - how long has this work been in your repertoire, and what special challenges does it present?

When I was in the second year of my postgrad at the Royal Academy of Music I was asked to sing it with the English Chamber Orchestra at Cadogan Hall: it was my first big professional concert, so I was really psyched about it! I got to know the piece through the Felicity Lott recording, and I remember sitting in the library with the score thinking ‘Woah, there’s so much French, and so many notes!’. And I probably learnt it slightly incorrectly, truth be told, as you often do when you’re a young singer…I know that’s the case now, because every time I’ve sung it since I’ve uncovered something I’d been doing wrong.

So there are some moments in there which still feel a bit unfamiliar, but for me that’s kind of the beauty of this piece – it somehow shape-shifts, so you don’t ever think ‘Yeah, I’ve conquered this now!’. Depending on where your voice is sitting at that particular time, certain phrases will feel easier or more challenging than they used to; your breath-control changes over time, and you have to rub out all the markings that worked before! I loved doing it, and hope I’ll record it again at some point in my life.

I performed it with 12 Ensemble at Wigmore Hall shortly before the recording, and it was just the most dramatic performance of it I’d ever done: I stood in the middle with the strings all around me, and it was really intense and difficult but also incredible! That was the first time I’d sung it off by heart, which was terrifying – I’d been determined to do it for years but never got round to it!

And did you conduct on top of all that?!

No, I hardly needed to do anything! They’re mainly the ones who lead, but it was all very organic: I didn’t do any conducting as such, even in the recording sessions. I have wondered sometimes about going down the whole singer-conductor road, but ultimately I’m not a massive fan of that approach: I’d rather work with musicians who can pick up on the tiniest things just through body-language rather than spelling it out with my arms.

And I do think something special happens when you don’t have someone standing at the front – it becomes a shared responsibility, because everyone is so much more alert to what they see and hear. At one point I did worry that the Ravel piece wouldn’t work like that because it’s very hard, harder than the Britten; we had to keep referring to the full score in the sessions and see what was lining up, but everyone stepped up and it came out really well.

How and when did you get to know the 12 Ensemble and the Ruisi Quartet?

During lockdown I put on a concert-series called Music at the Tower; I was just looking for groups to perform who were young and keen to keep making music, and along came 12 Ensemble. They did a Tchaikovsky concert, all standing in the round, and it was so cool; I got on really well with them, so when it came to doing this programme they seemed like a natural choice. I wanted to collaborate with a group who were used to working without a conductor, and they seemed the most receptive to the idea of it just being me and them – they’re very driven, and they’re not afraid of anything!

When it became obvious that the programme would also require a string quartet, it just made sense to use the Ruisi Quartet because they’re all members of 12 Ensemble, although they have different leaders: Eloisa-Fleur Thom leads the ensemble, and Alessandro Ruisi leads the quartet (his brother Max is the cellist, and his girlfriend Luba Tunnicliffe is the viola-player). It was a huge project to put together and it’s a tricky concept to sell to concert-promoters, but I loved the experience of working with different sizes of ensemble across one programme.

Robin Holloway's Ravel and Debussy arrangements are absolutely stunning - did you work directly with him on these pieces?

Robin used to teach one of my friends, Richard Wilberforce, and four or five years ago Richard was conducting a concert of his works in Cambridge; he asked me to join them for Robin’s chamber arrangement of Un grand sommeil noir so I ended up working with the two of them on that. I’d never really sung any Ravel before, and I completely fell in love with it; a bit later on I did the Mallarmé songs at Wigmore Hall and ended up feeling that he was one of my favourite composers to sing.

When the idea of the album came up I knew I wanted to record that big Ravel piece, and also that I wanted to do more French songs - but because Joe Middleton and I had already done an album of mélodies for voice and piano I decided to ask Robin to orchestrate some other songs as he did the Ravel. I left the choice of music completely up to him, and he came back with these four arrangements of Debussy’s Verlaine settings for voice and piano quintet.

I’d actually never sung any of those songs with piano before we made the recording – I have done so since, but I do love them with strings. It’s the interludes between the songs that are Robin’s real injections of himself into it: maybe some people will find it sacrilegious, or maybe I’m kidding myself that anyone will even care that much (!), but I’ll be interested to see what listeners make of them.

Did you study French language and literature formally before training as a singer?

I love singing in French, but I’m not a modern linguist by training. I did Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic at university, which is a very different beast: learning Anglo-Saxon is as difficult as learning Russian, because it’s a new alphabet, new sounds, a different way of speaking altogether. I wouldn’t even say that I’m a massive fan of poetry as such, in that I wouldn’t sit down and read it for its own sake - but there’s something very special about all those French poems of this era, especially when they’re set to music, and whenever I hear them sung in recitals I always feel very moved by the text.

People always say to me ‘So, have you ever used your degree?’. Hell, no! But if someone were to write a piece in Anglo-Saxon I should probably be the first to tackle it - you’d need someone who knew the language to set it and then someone who really knew it to perform it. I think if you gave me an Anglo-Saxon text it wouldn’t take me long to work out how to pronounce it, but I couldn’t translate it off the cuff – though I do know people who could!

Did you have a French-language expert on hand to advise on repertoire and pronunciation?

Helen Abbott has been my guiding light for the two French discs that I’ve done – I’ve known her since she was this incredibly clever nerdy girl singing alongside me in my dad’s choir! As her academic career blossomed we started working together professionally, and I quickly realised that she was an unmined source of incredible knowledge: she’s a Baudelaire specialist, and now has a professorship at Birmingham. When I floated the idea of a Baudelaire project (which became Voyages) with her, she unearthed these amazing Maurice Rollinat songs that had never been recorded before, and they ended up being the last two tracks on the album. Everything she suggested just locked in with the ideas I’d already come up with, and she did the same on this new disc.

Helen’s such a superb scholar, and she has all sorts of contacts who can get their hands on music that wouldn’t otherwise be available: for the Augusta Holmès songs on this album, she managed to call the Palace Library in Versailles and dig them out from there! Chabrier’s ‘Tes yeux bleus’ (which had also never been recorded) was entirely Helen’s idea as well: it was originally written for voice and piano, but again Helen had a lead on the composer’s own orchestral arrangement….

Two musicologists, Roy Howat and Roger Delage, had become aware that the French publishing house Jobert was closing its doors and was just going to get rid of all their music, so they went to Paris and rescued a load of manuscripts including this score – the place was in complete disarray and I think this one had ended up either in a skip or under a photocopier!

The orchestral arrangement of Fauré’s ‘Clair de Lune’ was my idea. I wanted to have an orchestration along the lines of the ones which Duparc did of his own songs, and I spent a lot of time searching for one online; I eventually found this performance by Natalie Dessay on YouTube, and loved it. It’s Fauré’s’s own orchestration, but the score and parts proved very elusive until Roy Howat again came to the rescue and tracked them down.

Where does Augusta Holmès sit stylistically in relation to the other composers on the album?

I didn’t feel she was that similar to any of them, really. If anything she was closer to the cabaret style, like those Maurice Rollinat songs I sang at the end of Voyages. Rollinat was alive at the same time as Debussy and performed at Le Chat Noir, where he would just accompany himself in these songs: the vocal line’s meant to be quite laid-back with no big singing, and that’s kind of how I classified the Holmès songs too.

I don’t know if anyone will notice, but Helen made a great suggestion here when she was sitting in on the recording as my language-coach. She told me I’d done all the pieces with a rolled ‘r’ (as is now traditional when singing in French), but with the Holmès songs she suggested I try a guttural ‘r’ to give it more of a cabaret feel, and it’s funny how much of a difference that made vocally. You can’t really support a guttural ‘r’ because it pushes everything too far forward; you have to be relaxed and fluid, and that’s a really nice way to sing.

How much has French opera figured in your career to date? I’d love to hear you as Debussy’s Mélisande…

I’ve never done any! I’d love to sing Mélisande, but it hasn’t come up so far – the opera isn’t performed all that often, especially in the UK, and I think that in France they’ve got such a burgeoning tradition of singers that they understandably want to use their own! I’m actually doing my first Rameau opera, Platée, in Zurich at the end of this year: I’ll be singing La Folie and Thalie, with Emmanuelle Haïm conducting. I’m so looking forward to it, because singing in French is very comfortable for me – much more so than German or even English!

Mary Bevan (soprano), Joseph Middleton (piano), 12 Ensemble, Ruisi Quartet

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Mary Bevan (soprano), Joseph Middleton (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC