Interview,

Nico Muhly & Nicholas Phan on Stranger

Commissioned by the tenor Nicholas Phan and premiered in 2019, Nico Muhly's Stranger is undoubtedly one of the most moving new vocal works to come my way this year: setting texts including extracts from letters and interviews with immigrants from China and Sicily, the song-cycle explores what Muhly has described as 'different kinds of shared American stories', and received its world premiere recording on Avie earlier this month alongside two of Muhly's previous works for tenor, Lorne Ys My Likinge and Impossible Things.

Commissioned by the tenor Nicholas Phan and premiered in 2019, Nico Muhly's Stranger is undoubtedly one of the most moving new vocal works to come my way this year: setting texts including extracts from letters and interviews with immigrants from China and Sicily, the song-cycle explores what Muhly has described as 'different kinds of shared American stories', and received its world premiere recording on Avie earlier this month alongside two of Muhly's previous works for tenor, Lorne Ys My Likinge and Impossible Things.

The three of us connected over Zoom last month to discuss the genesis and reception of Stranger, the questions around identity and immigration which lie at the heart of the piece, the pleasures of working with early English (as in Lorne Ys My Likinge), and Nick and Nico's shared love of the writings of Cavafy, whose texts are so beautifully set in Impossible Things...

Nick, how specific a brief did you give to Nico when you commissioned this cycle?

NP: It was commissioned to be the capstone of this giant project that we were producing at the Philadelphia Chamber Music Society, looking at song as an expression of identity; we did that through this lens of Paris around a hundred years ago and the rise of nationalism in particular. I described the project to Nico and he just sort of ran with it!

NM: Something that I’m noticing is that once upon a time your whole brief would just be ‘programme a recital!’ and now it’s more like ‘OK, the theme of our season is X, and the theme of this particular week is Y, and the Thursday is about celebrating and centring these voices…’. So there was a lot of extra-musical stuff that Nick and I had to wade through, and we focused in on this idea of immigration stories which, despite their specificity, would sing to a lot of people.

Nick, I think you and I narrowed it down to something that was personal to your journey (because you were on the stage having to actually sing the damn thing!) and then also to my own, making sure that I wasn’t writing something that was inappropriate coming from me with my very different background.

Was the choice of texts a joint decision?

NP: Nico’s the one who found these amazing texts, and he would shoot me random messages saying ‘Look at this wonderful quotation that I found!’. When he sent me that opening quotation it blew my mind - the question ‘How do you give voice to the voiceless?’ is such an incredible opening line for a song. The things he was finding were so brilliant and spoke to these incredible themes that we were trying to explore: it was more sort of me validating his choices in a way!

NM: I did a tonne of research on this, and I actually hired someone to help me go through everything, because a lot of these archives are either over- or under-catalogued: there’s been a fair amount of very digitised work on Jewish immigrants, a lot on Irish, an OK amount on Italians, and very little on Chinese and other East Asians (what there is centres on Japanese internments), so it was a case of finding the specific scholars who were working on those areas.

An equivalent for you guys in the UK would be the Windrush Generation: it wasn’t until The Guardian and the British Library started doing archival resuscitation and actually interviewing people that anyone knew much about it, so there’s a similarity there; as an American, it just never came up, even though there are so many resonances with our own history.

Nick, was delivering these kinds of texts rather than verse a new thing for you?

NP: I’d certainly never done anything quite like this, but I loved it – if you look at my library I tend towards scholarly historical research anyway, so it was very exciting for me to be able to combine that with my musical life.

NM: I love working with prose. I think that good poetry is really hard to set to music because it’s already got music in it, and sometimes by the time you’ve gotten to the end of the line you’ve forgotten what the beginning of the line was…These days I feel too old to get into setting a ee cummings cycle for voice and mixed nonet. I just can’t do it any more, so what you need I think is something either dead simple or a piece of prose, where the narrator (for want of a better word) is in charge of the story-telling in a way that would be almost impossible to do with a wonderful piece of poetry.

And the thing is that when you sing prose it turns into poetry in a strange way. Take that line from the Sicilian woman when she says ‘It’s the fear that you don’t know what you have in your eyes’: you couldn’t ask for a better line than that. Or that crazy last letter: ‘Perhaps it is the classical music on the radio, or perhaps it's just because it is Saturday night that has prompted me to write tonight’ – again, you could go through every volume of poems this side of the Euphrates and still not come up with something that precise!

NP: The other thing that was new to me was the third song, which sets a letter from Wong Ar Chong to William Lloyd Garrison – being given words written by a Chinese-American man was definitely a first for me, and that was a really transformational moment. As classical musicians we’re always dealing with these very antiquated ideas about boxes of identity, so if the text’s by a Chinese person the mindset is often ‘Oh, we have to get Chen Yi to write this, or model it on those songs that Britten set from Chinese poetry’. I’m not that kind of Chinese person, and this idea that I could sing something so closely aligned with my own identity was really powerful.

NP: The other thing that was new to me was the third song, which sets a letter from Wong Ar Chong to William Lloyd Garrison – being given words written by a Chinese-American man was definitely a first for me, and that was a really transformational moment. As classical musicians we’re always dealing with these very antiquated ideas about boxes of identity, so if the text’s by a Chinese person the mindset is often ‘Oh, we have to get Chen Yi to write this, or model it on those songs that Britten set from Chinese poetry’. I’m not that kind of Chinese person, and this idea that I could sing something so closely aligned with my own identity was really powerful.

NM: I've seen this a fair amount with artists from non-white (or particularly hybrid) backgrounds, where no matter what their artistic project is, they're asked to frame their work in terms of their identity: "how does your identity inform this work that you make". I see this happen implicitly and explicitly in visual art as well, where a gallerist or critic or patron really wants this kind of access. Even if the composer writes what essentially amounts ot high modernist music, which is what they love, there's still this pressure to reframe it; of course there are excellent composers who are very comfortable saying "I am X-American and I use traditional instruments from X in combination with traditionally western instruments..." and this is a beautiful thing. But sometimes it does feel like "these are the two genders! Choose one!".

Have you had chance to perform the piece live since the pandemic, and if so did it hit differently in the wake of the rise in anti-Chinese prejudice?

NP: The premiere was in Philadelphia, then after the pandemic we did it in Boston, New York, San Francisco and Chicago. In places like that you’re looking at an audience of similarly-minded white liberals who are nodding their heads in agreement, thinking ‘Yes this is very powerful and very moving’. But the last stop of that tour was in Scottsdale Arizona, and it was very jarring to do it there because Scottsdale is the land of Joe Arpaio who is this very anti-immigrant sheriff. Immigration is a big part of the political debate there. This is very close to where the previous administration was building a wall at the US-Mexico border.

It was super-interesting and intense, because in the last year-and-a-half the world has exploded and everybody’s angry about everything. When I was introducing the piece and explaining that it’s about how America welcomes (or doesn’t welcome) immigrants, you could hear these sharp intakes of breath in the audience as if they were preparing themselves to be challenged…they’d spent eighteen months arguing with people on Twitter about this stuff, and it kind of changed the way we approached it that day. You just have to lean into the humanity of these stories in order to find common ground with people who initially had a wall of resistance against the subject-matter, and that’s a very powerful experience.

It was a reminder of why being locked down was so challenging. Technology’s a great thing – look at the three of us sitting here talking right now from California and New York and Leamington! – but there’s something so potent about being in the same room and being forced to take twenty minutes or an hour together as opposed to relying on thirty-second soundbites. We share space and human energy and experience in order to focus on the things that pull us together as opposed to the things that pull us apart.

Nico, did you draw on any specific musical precedents for Stranger, as you did with Lorne Ys My Liking and Britten’s Abraham and Isaac?

NM: The Chester Mystery Plays are so linked to Britten in my mind - even more so listening to Nick, someone I can imagine singing Britten all the time because he’s so good at it. But Stranger was SO tailor-made for him that I didn’t want to let in too much of a draft from the past, whereas in Lorne Ys My Liking all the windows are open - I may as well have written it at Snape Maltings. It’s an incredibly Britten-ed out piece of music, whereas Stranger does a lot of different things, and I was pretty closed-off in terms of making sure that I was being true to the texts… It’s been interesting to see it slowly released movement-by-movement, because you realise how different the individual movements are, even though it’s one piece.

What are the pleasures and challenges of setting/singing in Middle English?

NM: Oh, I do it all the time! I love this kind of language: if I read the Bible I read it in the Wycliffe translation, so the really really early one!. Again, it goes back to Britten – if you’ve sung Ceremony of Carols as a kid you’ve sung something in early English, and I got bitten by that piece early. It’s pretty common in the Anglican tradition that I come from (look at pieces like Judith Weir’s Illuminare, Jerusalem, or the Adès Fayrfax Carol), but Nick I guess it didn’t come across your desk TOO often in recital…

NP: Not so much, no! The early English in Britten’s Canticle Two is somehow less daunting than in Lorne Ys My Liking, but Nico published a very helpful style-guide at the front! The words might be initially difficult to figure out, but once you have the meanings in your mind it becomes like singing in any language that you speak or don’t speak!

NM: There’s a piece of text that I add in the front of anything that has any early English which I think is the most useful thing. Whenever you do a piece like this there’s always one guy who’s just a little bit too into Chaucer and won’t shut up about it…it’s like the people who’ve memorised all the digits of π! In the wonderful tradition of doing evensong with 27 minutes' rehearsal you definitely don't have time for that conversation.

What draws you both to the poetry of Cavafy, as set in Impossible Things?

NP: Cavafy is someone who’s been mentioned in my household since I was a child because Greek people are very proud of Greek things! This honestly is the deepest dive I’ve taken into his poetry beyond just reading it – one of the joys of this job is that you really get to dig into multiple interpretations and it gives you a deeper comprehension.

NM: For me it was when I went to Columbia as an undergrad and was taught by Daniel Mendelsohn, from whose gorgeous book of translations these texts were taken. He was there teaching the core Classical curriculum at Columbia, and he’s such a wonderful writer: he published this gigantic book of translations with an enormous amount of scholarship at the end, and I realised that it was a delicious compendium of things that really could be set. And I think translation does something kind of magical to it, because you’re not working with the original: you really are setting it as a translation and translating it once again to get it onto the voice.

Impossible Things is essentially a double concerto for voice and violin, which is a little bit weird - but again Britten of course is the model, with the Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings. I think having this wordless body onstage plus the singing body is SO connected to what Cavafy’s often writing about, whether that’s happening in his imagination of antiquity or seen through a café in Alexandria…There’s this constant interplay between the desired and the desirer, similar to what you see in Death in Venice the way that Britten deals with the boy – he doesn’t have a Wagnerian theme, but what he has instead is this highly stylised gamelan music.

That’s kind of what I was trying to do too: take the Cavafy text and crack it apart a little by having someone play the hidden, undreamt-of body and all these fantastic turns of phrase…

Do you have plans to work together again?

NP: One of the concrete projects that’s been born of this is that Stranger is gaining an orchestration – there’s a Maine-based group called Palaver Strings that’s co-commissioned it with Daniel Hope and the New Century Chamber Orchestra, and it will premiere with Daniel and New Century in San Francisco in May of 2023. I have hopes and dreams of us doing another project. I’m constantly so star-struck by Nico…

NM: Oh, shut your mouth! You’re my favourite Pulcinella, you’re my hero! But putting these projects together is not easy, so we need to force the stars to align - we’d have to Jedi mind-trick random conductors and programmers and maybe in four years something will happen! But I'd do it in literally one second - Nick, just call me!

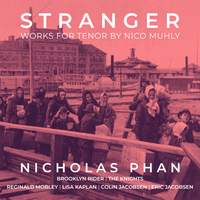

Nicholas Phan (tenor), Brooklyn Rider, The Knights, Reginald Mobley (countertenor), Lisa Kaplan (piano), Colin Jacobsen (violin), Eric Jacobsen

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC