Recording of the Week,

A double-bill of very different Baroque violin albums

Early music-lovers are often wary when we hear of a performer dipping their toe for the first time into the waters of historically-informed performance practice and period instruments. There are plenty of examples of musicians attempting to make this leap and not quite pulling off the landing. Fortunately, Nicola Benedetti’s first major foray into period performance is not one of them; her simply-titled album Baroque, doing exactly what it says on the tin in exploring concertos by Vivaldi and his contemporary Geminiani, is a triumph and an invigorating testimony to her adaptability and sheer musicality.

In Geminiani’s reworking of Corelli’s La Follia, the first thing that struck me was not in fact anything about Benedetti’s own playing; it was the ostentatiously florid continuo realisations. She mentions in the notes her initial surprise that the “humble harpsichord” could be “so multi-dimensional”; perhaps her continuo team wanted to make doubly certain that they’d dispelled such notions!

In Geminiani’s reworking of Corelli’s La Follia, the first thing that struck me was not in fact anything about Benedetti’s own playing; it was the ostentatiously florid continuo realisations. She mentions in the notes her initial surprise that the “humble harpsichord” could be “so multi-dimensional”; perhaps her continuo team wanted to make doubly certain that they’d dispelled such notions!

Benedetti herself, playing on gut strings for the first time, shows herself a ready pupil of the early music experts she’s been working with; her sound, shorn of vibrato, is initially dry and almost choppy, though she subsequently proves equally capable of presenting her customary lyricism via this new technique. A jealous Veracini’s spiteful comment that Geminiani and other prolific transcribers of his time were simply “rifriggitori” (re-heaters) of other people’s work misses the mark; in Benedetti’s hands Geminiani’s re-clothing of Corelli’s La Follia is fresh and still hot from the oven, no mere sad microwaved leftovers.

She comments revealingly that “The theme at the opening of the D major Concerto isn’t just a D major chord, but rather a grand entrance of fanfare and opulence”, and the performance here proves that these are not mere words, but borne out by actions. She and her orchestra capture the poise and hauteur of this opening as perfectly as anyone else I’ve ever heard performing this kind of repertoire.

The ever-popular Four Seasons, a staple of the repertoire for early and modern violinists alike, seems to have formed something of an initial bridge between Benedetti and Andrea Marcon, the conductor-harpsichordist of the Venice Baroque Orchestra with whom she did much of her exploration of this repertoire. Benedetti’s familiarity with that work shows in the other Vivaldi numbers featured here; her instinctive response to those characterically Vivaldian evocative passages that cascade down the cycle of fifths matches the orchestra’s, and amply demonstrates how comprehensively she has integrated this new facet into her musicmaking.

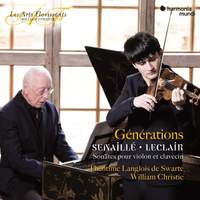

At the extreme opposite end of the scale, today’s other Recording of the Week sees early-music doyen William Christie team up with young Baroque violin specialist Théotime Langlois de Swarte to present a selection of French Baroque sonatas by Leclair and the relatively unknown Senaillé. The project seems to have come about as a consequence of a competition held by Christie’s ensemble Les Arts Florissants, but there’s no sense in the performances that de Swarte is in any way subordinate or taking the role of an apprentice; despite his youth and Christie’s vast experience, it’s a partnership of equals.

At the extreme opposite end of the scale, today’s other Recording of the Week sees early-music doyen William Christie team up with young Baroque violin specialist Théotime Langlois de Swarte to present a selection of French Baroque sonatas by Leclair and the relatively unknown Senaillé. The project seems to have come about as a consequence of a competition held by Christie’s ensemble Les Arts Florissants, but there’s no sense in the performances that de Swarte is in any way subordinate or taking the role of an apprentice; despite his youth and Christie’s vast experience, it’s a partnership of equals.

After the orchestral textures of Benedetti’s Vivaldi, the opening piece on this album is hauntingly lonely in its sonority, with just a single harpsichord line underpinning the violin in a Gavotte by Leclair. De Swarte achieves a convincingly vulnerable sound, here and elsewhere; the Sarabanda from Senaillé’s Sonata Op. 4 No. 5 opens with nearly a minute of unaccompanied violin, before Christie joins in first with that minimal single-note accompaniment and then, almost reluctantly, expands into a more conventional and fuller texture. This sense of reticence is by no means universal, of course; the Sonata Op. 1 No. 6, by contrast, has an air of profundity and grandeur about it that both de Swarte and Christie audibly lean into.

Senaillé was writing at a time when the violin was finally coming into its own in French society, and although born in Paris he studied for a time with Vitali in Modena, resulting in a style of composition that blends French and Italian elements. There are thus echoes here of the more overt theatricality of the Geminiani and Vivaldi works performed by Benedetti, tempered by a more refined taste. Between the exuberance of Benedetti’s new-found interest in the Italian Baroque proper and the more pensive partnership of Christie and de Swarte, these two albums make a perfect pairing.

Nicola Benedetti (violin), Benedetti Baroque Orchestra

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Théotime Langlois de Swarte (violin), William Christie (harpsichord)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC, Hi-Res+ FLAC