Interview,

Andrew Matthews-Owen on Taliesin's Songbook

Released digitally last month and now also available on CD, Taliesin's Songbook offers a fascinating overview of Welsh song from the early twentieth century to the present day, with music by Morfydd Owen, Dilys Elwyn-Edwards and Grace Williams sitting alongside more recent works by Huw Watkins, Mark Bowden and the late Alun Hoddinott. I spoke to the driving-force behind the project, Welsh pianist Andrew Matthews-Owen, about the remarkable lives and careers of some of the featured composers, his personal connections with the artists and repertoire on the album, the joys of singing in the Welsh language, and the cultural significance of Taliesen himself...

Released digitally last month and now also available on CD, Taliesin's Songbook offers a fascinating overview of Welsh song from the early twentieth century to the present day, with music by Morfydd Owen, Dilys Elwyn-Edwards and Grace Williams sitting alongside more recent works by Huw Watkins, Mark Bowden and the late Alun Hoddinott. I spoke to the driving-force behind the project, Welsh pianist Andrew Matthews-Owen, about the remarkable lives and careers of some of the featured composers, his personal connections with the artists and repertoire on the album, the joys of singing in the Welsh language, and the cultural significance of Taliesen himself...

Who was Taliesin, and how did he become the lodestar for this album?

Taliesin was a sixth-century bard, who really represents the dawning of cultural activity in Wales – he was the first to travel widely to Brittonic kings, taking his own ideas and performing in various courts outside of Wales and also bringing new things back. There are lots of different accounts of who he was, including tales in The Mabinogion, so I see him as a bit of a shape-shifter, almost like a Welsh Ariel. When I was devising this Songbook it occurred to me that lots of the composers I wanted to include were living at a time when they too could start to travel and absorb external influences, with many of them studying in London and further afield. There are so many new sights and sounds being shared in their music, and to me that sort of cultural exchange seemed to encapsulate the spirit of Taliesin, so that’s how I came up with the title.

And what’s incredible is that so many of these women composers - like Morfydd Owen, Dilys Elwyn-Edwards and Grace Williams - weren’t from wealthy backgrounds. Grace and Dilys both got scholarships to study at the Royal College of Music, and I love that. People often say ‘Oh, Wales is such a musical nation!’, and that’s pretty meaningless – it can’t be more musical than New Zealand or Africa or Japan! – but I do think that Wales has a great tradition of supporting talent. There’s a real sense of ‘Right, what can we do to help?’.

Alun Hoddinott’s last-ever orchestral commission, for his 80th birthday, was actually called Taliesin – I was lucky enough to be at the premiere in 2009, but sadly he’d passed away by then. It’s interesting that for his final score he chose to reference a figure who’s so strongly associated with renewal and the dawn of something new.

You mentioned ‘external influences’ – could you expand a bit on how that plays out in some specific songs on the album?

I think there’s a little bit of everything, because these young composers were being exposed to all sorts of influences for the first time. Morfydd Owen (who died in 1918 aged just 26) was very much influenced by Rachmaninov, and you hear that in the incredible breadth and richness of her songs on this CD. Dilys Elwyn-Edwards (who was born the year Morfydd died) studied with Herbert Howells, and they had a lifelong friendship and huge mutual respect: Howells was quoted as saying she was one of the greatest song-composers he ever knew. I liken Dilys’s songs to musical haiku, because they’re achieved with such economy of gesture: it’s just exquisite writing.

And Morfydd and Dilys were polar opposites in terms of their personalities as well as their musical language: Morfydd was an intellectual in the Hampstead set, whereas Dilys settled into a very humble life as the wife of a vicar.

How easy was it to get hold of the material for the Songbook, and how many of the songs are published?

They are published, and thanks to Tŷ Cerdd we had no problems getting hold of anything! Tŷ Cerdd are essentially the Sound of Music of Wales, and they’re such a fantastic team – they hold any manuscripts that are worth having by Welsh composers, and they’re incredibly generous about giving them out.

How much do we know about reception of the songs during the composers’ lifetimes?

I’m not sure how many reviews are kicking around, but these songs were certainly performed in the composers’ lifetimes. During the 1910s Morfydd Owen was really establishing herself as an independent career-woman, which is a fabulous thing to consider for that generation: she was a real emerging figure as a composer and pianist, then she married a psychoanalyst called Ernest Jones who was a protégé of Sigmund Freud, and he tried to quell this absurd notion of his wife having a career and a religion. Morfydd wouldn’t have that, so it was a very tempestuous union, but she was certainly successful in her lifetime.

Dilys Elwyn-Edwards likewise enjoyed great success, although she achieved it a bit later in life because once she’d completed a very successful studentship she essentially lived a quiet, very modest life. (My aunt, who’s now in her 80s and living in Canada, remembers Dilys being the maternity-cover teacher at her school in North Wales!). She taught at Bangor University, but didn’t push herself - then a generation of lieder-singers including people like Rebecca Evans, Bryn Terfel and Helen Field started championing her songs and performing them around the world. As a result she became very well-known as a composer outside of Wales, which I think her natural humility would have found quite confusing.

Did you have personal links with any of the composers and singers featured here before you began working on this project?

I know Huw Watkins and Mark Bowden very well (and knew Alun Hoddinott), and I think they’re such important voices. They’re both associated with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, and what’s particularly poignant about Mark’s cycle is that the words are by Gwyneth Lewis; Gwyneth’s words are on the Millennium Centre itself, where we recorded the disc.

Some of the singers involved in the project were already friends, and some were new to me and became friends. I remember going for a coffee with Susan Bullock so we could get to know each other, and she mentioned that her brother Dafydd wanted to write a song for us because every holiday they’d go to North Wales and see their grandmother in Llanberis…When I quizzed her on the name of the street where her gran had lived, it hit me that my mum used to talk about a lady whose granddaughter became a famous opera-singer, and I realised that it was Sue!

The project was full of these personal connections: everyone had a reason for doing the songs they were doing, and I loved that. Dafydd Bullock did end up writing that song, which Sue sings on the album: their grandmother and my mum both grew up in the shadow of Crib Goch, so we’ve privately dedicated it to people we love in Llanberis.

What are the pleasures and challenges of the Welsh language for singers who aren’t native speakers?

I do so much coaching with singers across the European languages, and I think Welsh is a great language to sing in. Look at the natural way that we speak generally: we just follow the vowels, like the Italians do. You can make an ugly sound with consonants if you want to, but always be fluid on a vowel! And the Welsh language is full of all sorts of wonderful guttural sounds and glottals: if you listen to Margaret Price singing in German, it’s no coincidence that it sounds so idiomatic.

This project focuses mainly on music from the early twentieth century to the present day – what did the Welsh song tradition look like before that, and might there be scope for another recording exploring it?

That’s something I’d love to investigate. I’ve picked up on this particular period because things got very interesting in terms of the professionalisation of Welsh music, but before that there was a lot of what we might call ‘parlour-room’ singing, and it would be interesting to explore that very localised and personalised type of music-making. The reason Wales is known as the Land of Song is that singing played such a huge role in mining communities, where it was a way to restore the spirits and unite communities.

That focus on local songs did continue into the later twentieth century and beyond, and in fact we’ve got two on the album, Evan Thomas Davies’s Ynys y Plant and Meirion Williams’s Gwynfyd. Welsh composers have this knack for writing big stand-alone power-ballads, and I think that’s one aspect of how this emerging professionalism played out on a local level. You’d have someone who was very much ‘the musician of the community’, and they could belt out this stuff like a Welsh Celine or Whitney!

Are there any live performances of the Songbook in the offing now that venues are starting to open up again?

Yes, and we’re lucky because there’s so many of us: we’re quite a big band of merry minstrels, like a Welsh SClub7! Rebecca Evans and I are doing a concert in Fishguard next year; Sue Bullock and I are at the St Ives Festival, and I’m also going to speak to the South Bank Centre about having a whole evening of this repertoire. These aren’t just songs - they’re the best of what we’ve got and the things we love, and I want to showcase that variety to as wide an audience as possible.

Are you aware of any plans to stage operas by Welsh composers in the near-ish future?

I know Mark Bowden is writing a large-scale opera with Owen Sheers for Welsh National Opera at the moment, but no other plans are afoot as far as I know. To me, the neglect of Welsh operas is just such a deprivation of some of our best sounds – you’ve got Iris Murdoch collaborating with William Mathias on The Servants, you’ve got Myfanwy Piper collaborating with Alun Hoddinott, you’ve got Arwel Hughes’s Menna, and Grace Williams’s The Parlour. I think it would be a crowning achievement for Cardiff to stage some of these works, when you think of everything that these composers did to enhance it as a musical capital. And we are a musical capital: we’ve got an orchestra and a national opera company housed in this fantastic complex, so it would be wonderful to have one of these operas there.

What else is on the cards for you in terms of recordings?

I was talking with a few colleagues about doing another CD of Welsh songs with chamber ensemble, such as Alun Hoddinott’s Grongar Hill which is scored for string quartet, baritone and piano. There are various other songs by Welsh composers using different combinations of instruments, so it would be great to explore those sound-worlds and put together something along the lines of the Britten Canticles…I'm also looking forward to recording a disc of French mélodies with Claire Booth for Nimbus.

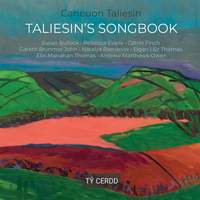

Andrew Matthews-Owen (piano), Rebecca Evans (soprano), Gareth Brynmor John (baritone), Susan Bullock (soprano), Elin Manahan Thomas (soprano), Catrin Finch (harp), Elgan Llŷr Thomas (tenor), Natalya Romaniw (soprano)

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC