Interview,

Leif Ove Andsnes on Mozart Momentum

The legend of Mozart the boy genius is so well-established as to have become a cliché – to have achieved as much in 35 years as most composers do in an entire lifetime would certainly require an early start, and the documentary evidence of Mozart's gifts in his childhood and teens is undeniable.

The legend of Mozart the boy genius is so well-established as to have become a cliché – to have achieved as much in 35 years as most composers do in an entire lifetime would certainly require an early start, and the documentary evidence of Mozart's gifts in his childhood and teens is undeniable.

But in his latest project, pianist Leif Ove Andsnes delves a little deeper – exploring the suggestion that it was Mozart's 1781 move from Salzburg to the more artistically competitive and stimulating environment of Vienna that really lit the touch-paper, catalysing his transition from a merely noteworthy musician into a name that would truly go down in history.

I spoke to Leif Ove about the remarkable turning-point year of 1785 that he has focused on, and about the complex pushes and pulls that were acting on Mozart at this time and helped to shape his music.

You’ve identified 1785 as a key year in which Mozart, having moved to Vienna and there encountered more professional competition, had to up his game. Do you think he would have become such an acclaimed genius if this move hadn’t happened?

It was such a big change to move from Salzburg to Vienna, and also to quit his job. If he had stayed in Salzburg I think he would have continued to write his wonderful church music, which we don’t have so much of after he went to Vienna. He was such a chameleon – his early travels with his father would have brought him to so many places where he could adopt the music and material that he heard – in Italy, Austria, Germany, everywhere he went he heard different music and it became part of his vocabulary.

If he had stayed in Salzburg and hadn’t had this opportunity, I think his musical language wouldn’t have been that rich. But also Vienna itself seems to have been a very liberal place in the 1780s, with [Holy Roman Emperor] Joseph II opening up for the arts, and it was really a time of opportunity – at least until the French Revolution. So it was a place which was certainly attractive to a lot of artists. We don’t know whether it was simply that Mozart developed from month to month and year to year, or if something specific happened there in 1785, but it certainly feels like he has to step up and create something new in the genre of piano concertos.

It’s quite remarkable – he had written six concertos the previous year, and then three in 1785 and another three in 1786, so we have twelve concertos within just three years, and with the kind of development in the genre which you’d expect another composer to take twenty years to develop. It was the kind of idiom that he was working most on at that time in his life, though he was remarkably productive in plenty of areas as well, writing The Marriage of Figaro in 1786 and the Prague symphony in 1785 – and the two piano quartets that we’ve included on this recording are also very much part of that.

It’s incredible what he does in the beginning of 1785, with more separation between the soloist and the orchestra – in the D minor concerto [K466] it’s the first time that the soloist enters with different material after the orchestral introduction, and that’s really revolutionary. It’s clear that he must have thought “I’m onto something here” because he follows up on it in his next concertos. For me it’s the very beginning of the Romantic piano concerto which is so well-beloved – where we have this more heroic role for the soloist. It’s much more individualistic, and separate from those around, which creates a new psychological drama in the genre and expands all the horizons.

Music was becoming more personal and individual at this time anyway – the whole Sturm und Drang movement, for instance – and it seems that Mozart wanted to write more of that serious kind of music, as in the D minor concerto for instance, but was often told by his father Leopold to think of it more as entertainment. But he wanted to push the limits of the genre, and obviously at this point we’re on the cusp of the French Revolution and all the ideals that come with that. I’m not sure if anyone was trying these ideas out before him, or whether he had any models that he was drawing on; it’s Mozart’s own development that’s particularly remarkable to me here. We think of him as this kind of Wunderkind but it took some time before his own music took on a recognisable voice. I think his first masterpiece is the ninth piano concerto, the Jeunehomme [K271], where in the second movement there is this kind of Schmerz and pain which becomes very typical for him in his concertos.

But yes, he develops this kind of language and it’s difficult to know exactly where it came from. Haydn, who must have been a great inspiration and model for composition to Mozart, very rarely has those kind of moments; it can be tragic but it’s rarely painful and it rarely changes so quickly from one emotion to another; the emotional diversity is not so rich as with Mozart.

In an age that we think of as being characterised by noble patronage, how common was it for composers and performers to “go freelance” as Mozart did from 1781?

I think this was an extremely bold move by Mozart – I can’t say for definite whether he was the first “freelancer”, and obviously he was still very dependent on supporters in the nobility for commissioning pieces from him and letting him teach. That’s one aspect that we often overlook in his life – he was teaching four hours a day every day, both gifted students and also the daughters of rich parents who could pay for piano lessons, and he was dependent on all that work. He may not have been the first pioneer but he was certainly really early within this trend.

We know, for instance, that Beethoven was never employed by anybody so he was perhaps the first fully freelance composer. He had patrons, of course, and I think Mozart did too, but they weren’t real long-term followers like Beethoven had – the Archduke Rudolf, for instance. I don’t think patrons play the same role in Mozart’s life.

Much has been written about later changes to piano manufacture spurring innovation by composers like Chopin and Liszt, but the notes accompanying this recording describe it as a “fast-developing piece of kit” even in Mozart’s time. In his works from this period, do you think he was pushing the instrument’s capabilities as well as his own?

The piano certainly does develop during this time, but when I think of this period I think of it as being essentially the same. The range expands slightly and the tone-production is a little larger, but it’s basically a Vienna fortepiano. When I think of the great developments in piano design that’s really post-Mozart, with some of the developments during Beethoven’s lifespan which are hugely interesting. From his first sonatas to his last, there’s an incredible change in how the piano has developed, and we can see that in his music – the range of the instrument, not just in pitch but in its capabilities more generally.

With Mozart, I don’t think this is so much the case. Indeed the harpsichord was still part of his world, at least early on, and one could argue that his first piano concertos might have been written for the harpsichord – so the fortepiano, or the Viennese Hammerklavier, was actually a new invention and was probably very exciting.

Over and above the Masonic Funeral Music, other works from the 1780s have connections to Mozart’s Freemasonry – one of these concertos was dedicated to his lodge, and he seems to have performed there frequently. Do you think this impacted the direction his compositions took, or was it simply another performance venue?

It’s interesting to look into. I find there is an aspect of his music that develops – and the Masonic Funeral Music shows this really well – that has something to do with a ritualistic soundworld, rather than the more obvious Mozartian quantities of rhetoric and beautiful melodies and sophisticated accompaniments and things like that. It’s more about the atmosphere – and the orchestration, with basset-horns and that kind of thing. It’s really interesting, this kind of music, and of course there’s a lot of that in the Requiem later on, as well as the kind of rituals we can hear in parts of the Magic Flute very clearly, and indeed in the C minor Fantasia [K475] which I’m playing on this recording there is also music of that sort.

He also met some interesting people, like the clarinettist Anton Stadler, through the Masonic lodge, and clearly this influenced him a lot. The fact that he brings the clarinet into his orchestration in 1785 in the piano concerto in E flat [K482]. He takes out the oboes and introduces the clarinets, which gives it a completely different feeling – sometimes it can be much darker than it would be with oboes.

Coming back to what I mentioned before about where these ideas come from, and why the music suddenly became so personal, it could very well be that it comes from the ideals he was encountering at the lodge – the development of personality and these things which were very important to the Masons there, and which he was very attracted by. There was a whole artistic side to it, which we might not think of today as an important part of the lodge, and also maybe an openness which he hadn’t encountered elsewhere.

This is the first of a planned double-bill of albums, with a second due to focus on 1786. Was there another seismic shift in Mozart’s outlook that year, or was he largely continuing to develop the new approaches he’d created in 1785?

He’s developing these ideas further. What I find extraordinary about the five concertos that we’ve included in this project is that they are not only very different in character but also in sound; it’s clear that he’s looking for really different soundworlds for each piece, at least at this point in his life. It’s something that becomes very clear when one plays them together and works on them together, as we’re doing here. That’s one of the wonderful things about the project, for me – to see clearly how he goes from the D minor to the C major [Elvira Madigan, K467] a month later and wants to create something completely different. There must have been plenty of the same people in the audience for these two performances, and his colleagues who were curious as to what he was up to, so I expect he wanted to show them different sides of himself.

Then when we get to 1786, there’s the famous A major concerto [K488], which is really in what you could call the clarinet’s key – the same key as he wrote his famous clarinet pieces later, the quintet and the clarinet concerto. It has a sort of heavenly light to it – it’s just so full of this particular kind of beauty that he finds in that key. He has such a sense of the different keys and how to use them. It probably has a lot to do with instrumentation and orchestration, and the possibilities he had there, but he’s really a composer with whom one does feel that the keys themselves are really important to the character of the piece. It’s a completely different sound and world from the previous concertos. There’s also this famous rather black second movement in F# minor – I don’t know of any other movement by him in that key. I expect there is something, somewhere, but it’s a very foreign key for him so that choice must have been very deliberate. It’s an extremely soulful and painful movement, but at the same time has a universal feeling about it, such as only Bach and Mozart can really unlock.

The C minor concerto [K491] is a very complex piece – the biggest one of all in terms of orchestration, as he brings the oboes back but together with the clarinet. There’s no other concerto by him where there is so much woodwind, and so much individuality in the woodwind writing. As the soloist I find myself sitting there for longer periods just listening to what they’re doing. And the chromaticism of the first movement is also very complex – it’s one of only two piano concertos he wrote in minor keys but they’re extremely different emotionally. Where the D minor is so obviously dramatic, fiery and restless, with a real Don Giovanni kind of atmosphere (and, incidentally, the same key as the overture to the opera, which might suggest again that Mozart ascribed certain qualities to the key), the C minor is more of an inner world – anxious and uncomfortable, and not easy to perform. I find that it always needs a lot of rehearsal time and lots and lots of nuance. It’s a very complex piece. Even just the beginning theme is almost like a twelve-tone theme.

NB: Recording for the second volume of Mozart Momentum has been postponed due to COVID-19 having forced the cancellation of Leif Ove Andsnes and the Mahler Chamber Orchestra's May 2021 tour. Mozart Momentum – 1786 is expected to be released in Spring 2022.

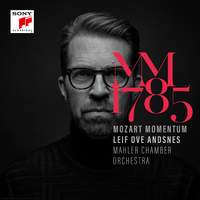

Mozart Momentum – 1785

Leif Ove Andsnes (piano), Matthew Truscott (violin), Joel Hunter (viola), Frank-Michael Guthmann (cello), Mahler Chamber Orchestra

Leif Ove Andsnes (piano), Matthew Truscott (violin), Joel Hunter (viola), Frank-Michael Guthmann (cello), Mahler Chamber Orchestra

Available Formats: 2 CDs, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC