Interview,

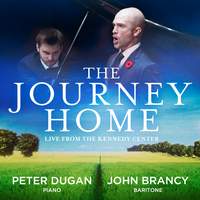

John Brancy and Peter Dugan on The Journey Home

To mark the centenary of the signing of the Armistice in 2018, American baritone John Brancy and pianist Peter Dugan embarked on an extensive tour of the US with an eclectic programme of songs paying homage to composers and poets who fought in World War One, focusing particularly on the aftermath of war and the difficult process of homecoming; featuring music by Holst, Schubert, Rachmaninov, Rudi Stephan, Ivor Novello, Vaughan Williams and Pete Seeger (plus a new commission by Dugan’s brother Leonardo), The Journey Home was performed in venues including Stanford University, West Point Academy, the Smithsonian Institute, and the US Naval Academy.

To mark the centenary of the signing of the Armistice in 2018, American baritone John Brancy and pianist Peter Dugan embarked on an extensive tour of the US with an eclectic programme of songs paying homage to composers and poets who fought in World War One, focusing particularly on the aftermath of war and the difficult process of homecoming; featuring music by Holst, Schubert, Rachmaninov, Rudi Stephan, Ivor Novello, Vaughan Williams and Pete Seeger (plus a new commission by Dugan’s brother Leonardo), The Journey Home was performed in venues including Stanford University, West Point Academy, the Smithsonian Institute, and the US Naval Academy.

In the run-up to the digital release of the live recording from the Kennedy Center (out today on Avie to mark Memorial Weekend), I spoke to John and Peter over Zoom about how they went about crafting a programme which would commemorate that difficult return journey without sentimentalising it, and how the experience of engaging with military communities across the States informed their perspectives on the music and texts…

Are there any musical traditions around Memorial Day in the US?

JB: All of the different sporting events around Memorial Day honour the military in some way, but I don’t know of any specific musical traditions. A lot of people tend to go on vacation for Memorial Day, especially this year when those who’ve been vaccinated will be travelling to see loved ones, and we hope that our film will be something that’s worth viewing together over the weekend.

This particular programme was designed in remembrance of Armistice Day, so the live recording is from November 12th 2018, the day after the centenary of the signing of the Armistice. The project was conceived as a new take on memorialisation, using the songs to commemorate events and to gain a deeper insight into these intense topics of discussion about our collective past.

You performed this programme at a diverse selection of venues in 2018, from traditional concert-halls to military colleges and museums: which locations or audiences particularly stood out for you?

PD: The US Naval Academy in Annapolis Maryland was definitely a highlight for me: we performed for an audience of midshipmen in full uniform, and it was a really powerful experience. The hall that we were in is actually called Memorial Hall: they hadn’t had a recital in there for fifteen years, and it’s not typically a venue that they would use for a concert because it’s a very hallowed space. There’s a tattered American flag hanging there which flew during the war of 1812, with the names of soldiers who were killed in action there on the wall behind us.

The folks on the administrative side were so welcoming, because there’s such a strong tradition of musical excellence there – the Glee Club is a big deal, as is the Naval Choir. The presenter from the Naval Academy explained to us that part of this goes back to the very earliest roots of being at sea: music and singing were essential to keep the oarsmen in time with one another, so you can trace this history of valuing music in the Navy all the way back to that. The community and audience there really embraced the music, and performing in that context made us see these songs in a whole new light.

JB: They really packed the venue – it was literally full of midshipmen! The Air and Space Museum at the Smithsonian Institute came on board too, so we were able to give a very intimate recital there for people who seemed very educated on the topic and already knew a lot of the songs; that took place on 10th November, and was another moment that really stuck out to us.

PD: That concert was live-streamed, so we had people watching from all over the world – live-streams are kind of normalised now, but back then it was all very exciting! The Smithsonian has such a huge following on social media, and when we went backstage at the intermission we saw that their Facebook stream had gathered about 40, 000 people - for an art-song recital! So one of the most intimate performances of the tour also turned out to be the one with the largest audience.

JB: That was a big thing for the tour in general – we used the film which we created as an opportunity to push boundaries, not only with the livestream but also in terms of finding our way to military academies like West Point. It was always about getting the most out of being in those communities, but also taking the opportunity to actually film there and preserve moments which we knew were going to be very special.

And that idea of pushing boundaries also plays out in your programming-choices…

PD: The whole premise is these themes are universal – the idea of ‘The Journey Home’ transcends which side you’re fighting for and also transcends time. That’s why we included Schubert, to emphasise the fact this ‘homecoming’ is not an experience that was limited to World War I. With the pop music, part of the joy of that is to present it in a way that recognises the limitations of these songs, and questions how accurately they represent the truth of a soldier’s experience. Take ‘When the boys come home’, the first song on the programme: John strides on stage and sings this apparently upbeat number, and afterwards we reflect on what actually happened and how many of ‘the boys’ just didn’t come home at all…It was very important for us to reveal a deeper truth about this dichotomy between how popular culture sometimes celebrates these things and the lived experience of those involved.

What was the starting-point for your programme In terms of repertoire?

JB:: The Songs of Travel is such a famous cycle, and it was part of the first recital that Peter and I ever performed together as teenagers at Juilliard. But Schubert’s ‘Der Wanderer’ was always the anchor of the whole programme, because of the story – it’s important to see it in the context of the Wanderer having gone to war, then finding that the home he longed to return to has been essentially decimated. That allowed us to connect various dots along the way, and it all kind of coalesced around April 2018 when Peter and I gave the premiere performance of Leonardo Dugan’s ‘I Have a Rendezvous with Death’ at Alice Tully Hall: we were given the opportunity through our alma mater, Juilliard, and we put this recital together as a sort of sequel to the first programme that we did around the idea of war. That one included a lot of these popular tunes, but it didn’t ever really touch on the end of the war and what happens when things go back to ‘normal’…

PD: To put it in really simple terms, that first album was the Iliad and this one is the Odyssey. The first one was all about the actual experience of war and the devastation and loss it involves; it was a heavy programme, featuring music by composers who actually served in the World Wars including Butterworth, Gurney, Orff, and Poulenc (who served in both). The idea was that this one would be a companion to it and explore what 'the journey home' was like, and in the film that we made we continued that exploration through interviews with a range of historians and representatives from various branches of the US military.

How did the songs by Rudi Stephan come into the picture?

JB: We programmed the Stephan partly in order to make sense of ‘Der Wanderer’. Vaughan Williams was a medic in World War I, and the songs that we do by Peter’s brother Leonardo are explicitly about that period, so there’s specificity in the story up to that point...but we really wanted to find a way of integrating the Schubert. I kept digging and found these two songs that are a mini-cycle, and they proved an ideal fit: they were written right before Stephan went to war, and they’re also very clearly related in the text to ‘Der Wanderer’.

PD: There’s a moment in Stephan's ‘Memento Vivere’ where the character’s feeling lost and alone, and hears a ghostly voice that’s going out to him…It’s exactly the same sort of literary framework as ‘Der Wanderer’, and we hit on the idea of sandwiching them together so that Schubert becomes that ghostly voice from the past, speaking to us from beyond the grave. And the transitions between the keys work out perfectly, so we go straight into ‘Der Wanderer’ from Stephan’s ‘Am Abend’.

JB: It’s almost uncanny that they all work together like that - it’s like one large song of seven minutes.

PD: We made ‘Du bist die Ruh’ the end of that set: the C major feels so clean because it comes right after ‘Memento Vivere’ with those crunchy harmonies, so there’s a real feeling of catharsis.

JB: And ‘Du bist die Ruh’ conveys a timeless message of peace: the idea is that you are peace, ‘home’ is here, and you are able to find it within yourself. I think that’s what the search is ultimately about for lots of people.

Peter, how did the new commission from your brother Leonardo come about?

PD: ‘In Flanders Fields’ was our idea: the concert was being co-presented by the government of Flanders, so we reached out to them and said we’d like to do a setting because there hadn’t been a good one since Charles Ives (and his is still very 'rah-rah'!). When we approached my brother, he said ‘I’ll write it, but that last verse can’t be a rallying-cry for war: we have to think of it as if the foe is war itself’. Leonardo knew that we wanted something very melodic, but in terms of actual setting we pretty much let him get on with it! And it all ties into this theme of trying to break the cycle of violence, which then gets addressed in ‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone’ too…

JB: Leonardo’s songs work as a little mini-cycle, where Peter’s arrangement of Pete Seeger’s ‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone’ is the final piece: Alan Seeger (Pete’s uncle) wrote the text for ‘I Have a Rendezvous with Death’, then ‘In Flanders Fields’ talks about the poppies, and that segues into ‘Flowers’. So that triplet of songs operates as a journey on its own, ending with the words ‘When will we ever learn?’

PD: The whole film wraps up with a quote from Jason Musteen, a colonel in the US army and a history professor at West Point, who spoke to us about the idea that mankind is a ‘forgetting machine’: collectively we forget the trauma of the past, but the individual man or woman who’s experienced it will remember, and that basically our challenge is to try and remember that individual suffering so that mankind can break the cycle.

You’ve obviously done a huge amount of research in terms of talking to contemporary military historians and servicemen about their experiences of war – were there any primary sources dating from World War One which had an impact on the programme?

JB: There’s a very powerful letter which Vaughan Williams wrote to Gustav Holst in 1916, and when we found that everything really came together in terms of this programme and the previous one. Holst actually mentions George Butterworth by name, so it’s almost a meta-narrative; we read the letter from the stage, right before the Songs of Travel.

PD: And that’s also why we included my arrangement of ‘Jupiter’ from Holst’s The Planets. In the letter Vaughan Williams expresses how on the one hand he longs to return to normal life, but on the other he dreads going back because it’s not going to be the same. That’s what every soldier has to deal with, and is essentially the heart of The Journey Home.

John Brancy (baritone), Peter Dugan (piano)

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC