Interview,

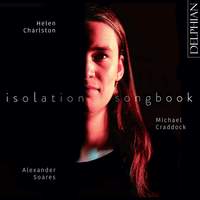

Helen Charlston and Michael Craddock on their Isolation Songbook

For my money, one of the most striking recording-projects to emerge from the past year's lockdown is The Isolation Songbook (released on Delphian last month) - a fierce, funny and moving anthology of songs and duets commissioned by mezzo Helen Charlston and her fiancé Michael Craddock, which features music by composers including Owain Park, Héloïse Werner, Kerensa Briggs and Andrew Brixey-Williams.

For my money, one of the most striking recording-projects to emerge from the past year's lockdown is The Isolation Songbook (released on Delphian last month) - a fierce, funny and moving anthology of songs and duets commissioned by mezzo Helen Charlston and her fiancé Michael Craddock, which features music by composers including Owain Park, Héloïse Werner, Kerensa Briggs and Andrew Brixey-Williams.

It was a real pleasure to 'meet' the couple on Zoom recently to discuss how what began as a low-key, highly personal project snowballed into something much bigger, the logistical challenges of learning an entire raft of new compositions without any in-person contact with the composers, and their plans for taking the Songbook out into the wider world as restrictions on public performance ease...

How often did you get to sing together pre-lockdown?

HC: We met through singing together at university, so it’s always been a part of our lives, but over the last few years we’ve done a lot less together: we have one group that we run jointly, Amici Voices, and we sometimes overlap with our work for the Gabrieli Consort, but that’s about it!

Where did you start with the call for submissions for this project?

HC: It was immensely open-ended, and we didn’t have huge plans for it initially. It all started in April and May of last year, when everybody was thinking that things would open up pretty soon and it would be nice and easy to get back into performing, then suddenly things in the diary started disappearing for a lot further down the line than we’d anticipated… We just thought it would be really nice to have some songs that Mike and I could sing at home: there’s only the two of us in the house, and once we got over the shock of the fact that everything had fallen away we started thinking about how we could make music together.

The original premise was a maximum of two singers, with a piano-part that we could play ourselves – Owain’s piece, which is the first one written, actually has little moments marked in the score where one of us stands up and the other goes to the piano! Once the scores started coming in we quickly realised that it was turning into a bigger project, so that element of things disappeared, but it was quite entertaining while it lasted!

For the concert and recording we were joined by pianist Alexander Soares. Alexander and I are both City Music Foundation Artists, but this was the first time we had actually worked together – so it was wonderful that we were able to forge this new working relationship despite the pandemic.

How did things progress in terms of taking this music beyond your living-room and out into the wider world?

HC: I’m supported by City Music Foundation, which provides career development and management for artists at the start of their professional careers. , Because of lockdown CMF rearranged its 2020 concerts as a series of live streams from St Pancras Clock Tower, and they helped with fundraising, and promoting the world premiere concert from there. They’d given me a slot at the end of July, so suddenly we had a goal to work towards and were able to tell the composers that there was a real concert in the pipeline: I think a few people got involved because of that who maybe wouldn’t have done otherwise.

MC: And it also gave us motivation to raise some money to pay the composers, which felt quite important to us – everything was disappearing and commissions were falling through left, right and centre, so we didn’t want to end up just chatting on Twitter and putting out a call for scores without giving anyone any sort of remuneration. Artists fees, live stream equipment and team, video and venue were all covered by City Music Foundation to keep musicians in work during the pandemic and we wanted to do the same for the composers. That was an initial principle.

Were all of the composers who responded people who were known to you already?

MC: It was a bit of a Venn Diagram situation: there are some people I know but who Helen has never met, and vice versa. But there are three or four composers we’ve never met at all, including Derri Joseph Lewis and Richard Barnard.

Helen, your dad was one of the contributors – had he composed anything for you before this project?

HC: He’s wanted to write me something for a while, but this was his first attempt! He’s a professional harpsichordist by trade but he’s started composing quite a lot more in the last few years, so it’s been a nice little exploration for him as well. His other big project at the moment is a set of clavichord duets for him and Julian Perkins, and they really are fantastic!

How much contact did you have with the composers whilst they were writing?

HC: It was different for different people: some asked for information about tessitura and register, but most were very happy to just forge ahead, and it was amazing when these pieces suddenly appeared. I think it was a particularly rewarding way of doing it for us: while it wasn’t necessarily hugely collaborative in terms of what was being written, our role was to figure out how the jigsaw would all fit together. The variety of mood and style was down to sheer luck - and it’s amazing that cows appear twice!

How difficult was it to learn so much new music at home in such a short space of time?

HC: On a practical level, we have the world’s best neighbours: we live in a ground floor flat with them above us, and we do sing a lot…They genuinely are saints!

MC: It was helpful that the commissions came in dribs and drabs: it wasn’t as if a whole book of music arrived at once, so we had time to go and play around with things, and we did actually end up performing everything that we received. The one exception was Elliott Park’s Skysong, which is a full-blown song-cycle: he’d recorded 24 hours of birdsong over the course of a whole day, and that weaves in and out of the full set of songs, which ended up being too much music for the recording. I think we basically selected the ones which were the least scary for this project, but the rest of the piece is just brilliant and eventually we’ll give the full thing an airing!

Did lockdown restrictions have an impact on the recording-sessions?

MC: The recording happened in September, so it was quite relaxed in terms of restrictions. We were up in Edinburgh at a time when people could travel – effectively we had a little holiday.

HC: The beauty of a small-scale project like this is that it’s much easier to put together from a COVID perspective. And we were in the Queen’s Hall, which is such a great space – despite all of its challenges, the past year has also thrown up some amazing opportunities, because under normal circumstances there’s no way we’d have had that venue to ourselves in the first week of September. I found it quite inspirational to be somewhere like that having not done any concerts or been in any big spaces for a while.

MC: Yes, you get to the point where you forget what an acoustic sounds like! The biggest space we’d been in was the Clock Tower when we did the City Music Foundation concert, and that’s not a big room. But the recording was as pain-free an experience as possible – Paul [Baxter, Delphian’s founder and engineer] is brilliant, and especially so for this kind of music. He’s so methodical and meticulous, and because this programme has so many different moods it was great to have someone who’s happy to let you lay out the whole thing and then break it down and get it on record with as little fuss as possible. He knows you know how to sing the music, and just lets you get on with it!

Which pieces posed the biggest technical challenges?

HC: For me it was Andrew Brixey-Williams’s Abat-jour. It’s got a lot of complicated cross-rhythms going on and big beats broken into five, (which is really hard!); it was definitely the song Alexander and I spent the most time rehearsing. But now it’s sung in I’m really looking forward to getting that into as many programmes as I can, because it’s absolutely extraordinary music..

MC: I thought the unaccompanied pieces were quite difficult to put together, because you end up singing in a different idiom once you remove the piano. Especially with two-part writing, you get so much choice about where everything goes – it’s a little like solo cello writing in that so much of the harmony is implied in your head, so it’s a very different exercise from singing songs with piano. But all of them are very well written, which made things easier than they could have been!

Helen’s dad’s piece has the voices right on top of each other, with lots of tricky intervals...and once we’d learnt it all he rang us up and said ‘Actually, I wrote it at the clavichord so it should be done at A=415 – just put it down a semitone!’. Neither of us have perfect pitch, but it’s amazing how much you rely on muscle-memory with difficult things.

And which were the most taxing from an emotional perspective?

HC: I had quite an immediate response to Stephen Bick’s On his Blindness: Milton’s poetry itself is amazing and the way Stephen set it is incredibly moving. We knew very early on that it had to be the end of the set – for some reason it had that feeling of cohesion and completion to it.

MC: Yours is the end, and mine’s the beginning – for me it’s Owain Park’s piece, 18th April, because there’s inevitably a lot of personal stuff tied up in that. It’s hard to separate the personal and professional with a project like this: this is a piece that obviously means a lot to us, and putting it out there to everyone was an odd shift, especially as when we received it we didn’t think it was going any further.

HC: That piece was the start of the project: I got Owain to set a poem I’d written as a gift to Mike for our 'not-wedding-day', but it’s nice that it’s got a further life.

Is the piece going to make an appearance on your actual wedding-day?

HC: We still have to decide what’s going to make the cut…

MC: We had all our choices nailed down, but most of them are going to be untenable given restrictions on numbers so it’s back to the drawing-board… But I think we’re certainly going to have a day off singing at our real wedding – maybe we’ll get somebody else to do it!

Do you have plans to perform any of the other songs out of context?

HC: I’m singing two pieces from the Songbook with Chris Glynn for a recital that Ryedale are putting out in the spring – it’s themed around nature, so obviously Joshua Borin’s Nature is Returning is going to be in there… I’m really keen to find ways of programming these pieces in other contexts, because while this music has been streamed and recorded it literally hasn’t been in a room with anyone other than the three of us yet, and that’s weird: even the composers haven’t sat in and listened to anything. Once we know what’s possible with audiences we’ll sing it to anyone who wants to hear it!

And are your diaries getting back to something approaching normality as restrictions lift?

HC: There’s been a sudden hive of activity recently, which I feel very lucky to be part of - I’ve done three John Passions and a Matthew Passion over the last six weeks, so it’s almost like real life! One of them was an absolutely fantastic John Passion with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, which was streamed for Holy Week: it was all unconducted, with Mark Padmore leading. Alongside that, Mike and I brought Amici Voices together for a one-per-part performance of the Matthew Passion from St John’s Smith Square, which has been really special and another way for us to enjoy the novelty of working together in this time.

MC: I’ve been up in York doing the Early Music Festival, filming a whole bunch of things with the Gesualdo Six, and it was really nice to be somewhere that wasn’t my house!

Helen Charlston (mezzo-soprano), Michael Craddock (baritone), Alexander Soares (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC