Interview,

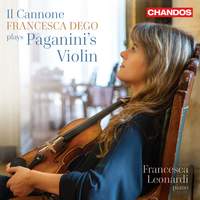

Francesca Dego on Paganini's Violin

Italian-American violinist Francesca Dego has long displayed an affinity for the music of Paganini, recording his first violin concerto in 2017 to especially great acclaim. She now draws even closer to the soul of the iconic violinist-composer with an album recorded on the violin that he himself played – almost 280 years old, bequeathed to the city of Genoa on his death and leading a double life as museum-piece and musical instrument ever since.

Italian-American violinist Francesca Dego has long displayed an affinity for the music of Paganini, recording his first violin concerto in 2017 to especially great acclaim. She now draws even closer to the soul of the iconic violinist-composer with an album recorded on the violin that he himself played – almost 280 years old, bequeathed to the city of Genoa on his death and leading a double life as museum-piece and musical instrument ever since.

Rather than simply presenting an all-Paganini recital, Dego has explored composers who were influenced by or linked with Paganini – Kreisler, who arranged his La Clochette from Paganini's second violin concerto; Rossini, who dedicated a chamber work to his memory; Schnittke, whose A Paganini quotes over half of his fiendish Caprices, and more. I spoke to her about this album, and about her small wooden co-star – the famous 1743 Del Gesù that she plays.

This recital is built not just around Paganini’s music but around the instrument he himself played, a 1743 violin by Giuseppe Guarneri. Today access to the 'Cannone' is highly restricted; how did you end up recording an album on this precious historical artifact?

The City Council of Genoa, and the Teatro Carlo Felice, with the support of the Enzo Hruby Foundation, wanted to organise a concert on October 27th 2019, Paganini’s birthday. I had recently performed Paganini Concerto No. 1 as part of the “Stars of the White Nights” festival at the Mariinsky Concert Hall in Saint Petersburg with the Carlo Felice Orchestra and was honoured when I received the invitation to perform with 'Il Cannone' on this very special occasion back home. The possibility to record came as a direct consequence and I was lucky enough to have the enthusiastic support of Bruce Carlson, conservator and restorer of “Il Cannone”, who supervised every practical detail together with a security team of six (who never left the room while I recorded and came on stage with me for the performance!). I initially thought they looked quite menacing, but by the end of the week we were sharing pizza and good laughs.

I had wanted to record some of this repertoire for quite some time. To pay homage to Paganini through the notes of composers who worshipped him was a recurring idea so when I suddenly had the chance to do it on his very own violin it was a dream come true, especially since the violin has pretty much played only Paganini for its entire existence! I was set on giving listeners the chance to hear this amazing instrument in very different contexts and soundscapes it hadn't yet explored.

The 'Cannone' ’s curator, Bruce Carlson, comments on the balance to be struck between preserving centuries-old instruments and allowing them to serve their original purpose – that is, making music. How do you think we can best resolve this paradox?

The question of what the Cannone would sound like if played on a daily basis has accompanied the violin since Bronisław Huberman briefly performed on it in 1908, followed by a lucky handful of the world’s top soloists. But what of Paganini’s request that it be cherished and protected for posterity? It’s not only an artistic issue but a legal one: What exactly did he mean? It belongs to the city so the question isn't only “how much” it can and should be played, but by whom! As much as I’d like it to be played - and any violinist will tell you that an instrument must be played to sound its best - I do understand what Bruce means when he stresses how conservation of a violin in such a rare state of preservation must necessarily be the primary goal, at least until we know more about how to protect it and share all its potential with future generations.

The instrument has had an immensely longer history than most instruments that are played by living musicians. How much of a distinct personality do you feel it has; did it take much “getting used to”?

I love this quote by Yehudi Menuhin, which I also included in the album’s booklet: “a great violin is a living thing; its very form embodies the intentions of its maker, and its wood contains the history, or soul, of those who later possessed it. I can never play without getting the feeling of having freed or, alas, violated these spirits”. Considering that Paganini was the last player to “shape” the sound of his beloved Del Gesù for more than a fleeting encounter, it is almost overwhelming to think that by playing it I had the chance to get so close to his sound and soul. The violin is indeed very special, and responds best when you listen to it and let it breathe. For me this meant not using too much bow pressure or force to avoid suffocating its prodigious overtones, and looking for ways to make every small movement, shift and string change effective rather than showy. I’ve described it as having a “no-nonsense”quality: it hits back when bullied. It definitely warmed and “opened up” to me, becoming easier to play as the hours went by. This went from obvious aspects (in the beginning I had to stop and tune it every few minutes) to the fact any instrument needs time to adapt to vibrating after any period of silence. That said, it’s remarkably healthy and is kept in top playing conditions.

Paganini – using the 'Cannone' throughout his career – is well-known for having driven violin virtuosity to new heights. How much of the credit for this do you think is due to the exceptional quality of the instrument itself?

Each and every violin has its own unique identity which will play a vital part in a performance. With experience you learn to look for the instrument’s strengths and weaknesses and to let it breathe, enriching your desired palette. I’ve always found it impossible to recreate an identical effect with different violins and I’m sure it was the same for Paganini: you find inspiration in what the instrument is telling you and you make it your own. It’s so exciting to imagine him exploring and composing TOGETHER with this violin. Most of the technical aspects in his compositions, some of which he even invented himself, reflect his will to imitate the vocal lines and theatrical effects he grew up listening to in opera houses and I think the majestic and highly responsive quality of Il Cannone embody the richness of sound he was looking for. For example it has a prodigiously powerful and smooth G string and I can definitely see why he’d want to show it off in compositions like the Moses Fantasy, where he completely disregards all other strings! At the same time it has a very special ringing quality that helps project harmonics (among the most demanding technical effects we find a lot of in his compositions, where the violin sounds like a very high-pitched flute!) work more naturally than usual.

Exceptional instruments, like artworks or sculptures, are of course worth unimaginable amounts of money, and every so often one is lost, damaged or stolen – or has a hair-raising near miss. Were there any such anxious moments during your few days with the 'Cannone'?

I was never anxious about the violin not being safe with me: I consider myself extremely clumsy but I have only every damaged one instrument (by tripping and falling over onto it), when I was five years old! The armed guards take care of the whole “theft” scenario by staring at it all day but I have to admit that Pio, one of the curators, looked quite alarmed when I started recording the Schnittke… I planned it in the last session, literally in case they decided to make me stop! Schnittke ingeniously combines his own fiercely virtuosic and exciting language with quotes from 13 of Paganini’s caprices but I do realise it can sound a bit rough and out of control! For the last note you even have to tune down the G string to a C# and I knew from the start that I only had one chance of getting this right: the G string would have needed a long time to settle back into its original pitch if I had to repeat the passage! I’m sure Paganini would have loved this piece.

Carlo Boccadoro’s Come d’autunno was written especially for you in 2019. Can you tell us how this piece came about – and how it reflects the poem Soldati on which it’s based?

Carlo Boccadoro is one of Italy’s most celebrated and performed living composers. His language is very distinctive and I especially appreciate how he manages to adapt it to every instrument without distorting its voice and soul. I asked Carlo to write a piece inspired by Paganini and his “voice”, 'Il Cannone', and he came up with a gorgeous miniature which somehow manages to give us the feeling that Paganini’s spirit is playing with the musical material but at the same time finds inspiration in other geniuses of Italian artistic history, including Dante (“As in the autumn-time the leaves fall off, First one and then another, till the branch Surrenders all its spoils to the earth; In similar fashion did these evil seeds of Adam throw Themselves from the group, one by one, into the boat At Charon's signal, as a bird is called to its lure.”) and twentieth-century poet Ungaretti with his poem 'Soldiers', which describes the fateful lingering of time during WW1 (We are as/ in autumn/ on branches/ the leaves). It’s almost as if history, in the form of this iconic violin, pride of Italian craftsmanship, is connecting these artists and the hardship they endured to the horribly unsettling atmosphere we’re immersed in today.

Francesca Dego (violin), Francesca Leonardi (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Francesca Dego (violin), City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Daniele Rustioni

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC