Interview,

Hélène Grimaud on The Messenger

Mozart and the Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov (b.1937) might not, on the face of it, seem like the most obvious of bedfellows, but French pianist Hélène Grimaud’s The Messenger - released towards the end of last year on Deutsche Grammophon – underlined some unexpected connections between the two, and I found myself returning to the album time and again throughout the long winter evenings thanks to its peculiar atmosphere of melancholy tinged with hope.

Mozart and the Ukrainian composer Valentin Silvestrov (b.1937) might not, on the face of it, seem like the most obvious of bedfellows, but French pianist Hélène Grimaud’s The Messenger - released towards the end of last year on Deutsche Grammophon – underlined some unexpected connections between the two, and I found myself returning to the album time and again throughout the long winter evenings thanks to its peculiar atmosphere of melancholy tinged with hope.

Hélène and I spoke via Zoom before Christmas about the particular affinity which she feels with Mozart’s minor-key works, the birthday-present which sparked her fascination with Silvestrov’s music, and how a spontaneous afternoon in Paris a few years ago led to a musical epiphany…

How did your passion for Valentin Silvestrov begin, and what spoke to you about his music?

It was through the Silent Songs cycle, via an ECM recording which Manfred Eicher gifted me on the occasion of my birthday maybe fifteen years ago. I found the music to be absolutely spellbinding: it had this hypnotic quality that made everything around you go still, and I remember being drawn in and feeling that there was this endless depth there. There’s something so poetic and haunting about it all, and that was really what got me hooked into his world.

Have the two of you had any direct contact?

Unfortunately not. It’s a strange thing with composers, though: even though I would give a lot to meet some of my favourites such as Beethoven, Brahms or Rachmaninov, I feel you can never be more intimate than by simply being in contact with their music and actually producing the sound that’s required for it to come to life. Maybe it’s better to leave it at that!

Did you select the Mozart works on this recording to complement musical ideas which are also present in the Silvestrov pieces?

The Mozart side of the programme was always clear to me from the beginning – Silvestrov came a little bit later. I’ve always been more drawn to the Mozart pieces written in minor tonalities: those were his most dramatic works, and in that sense you feel that Beethoven is already happening, so it’s also music of the future. It speaks of a world to come, and what I find so compelling about these pieces in D minor and C minor is that idea of an appointment with fate or destiny: I always knew that it was going to be the D minor concerto, preceded by the D minor Fantasia (minus the last ten bars, which weren’t even by Mozart and were added later on so that the Fantasia could be played as really intended, in the baroque style as a prelude to something else). And then we have the C minor Fantasia, which I think is a fascinating piece of music – it’s so complex, and probably one of his most difficult works.

You mentioned foreshadowings of Beethoven – do you feel that there’s also a sense of Mozart looking back to the baroque as well as forward to early Romanticism in these minor-key works?

Not much, actually! I suppose as is often the case when destiny shows up, you could say you’re looking back to the day when everything changed…that’s certainly intensely dramatic, but otherwise it’s all about what’s supposed to happen next, and in these Mozart works I absolutely feel the sense of abject terror which comes with that anticipation.

Were you always clear that you would use the Beethoven cadenza for the concerto?

Absolutely - even though there are many interesting cadenzas by other composers and colleagues I still find Beethoven’s to be strongest. Given the D minor tonality and this element of destiny and fate, it’s no surprise that this was Beethoven’s favourite Mozart concerto: there’s no doubt in my mind that he was strongly influenced by that piece, as I’m sure he was by the Requiem, or Don Giovanni, or the C minor piano concerto.

Did you direct the concerto from the keyboard?

I wouldn’t call it ‘directing’, because for me the best thing that can happen when you work with an orchestra is to have a chamber-music event on a large scale. That can happen even with a symphony orchestra – it’s harder to achieve, because you have to have total freedom and chemistry with the conductor – but with a chamber orchestra I would say everything takes place in the rehearsals. Let’s face it, musicians at this level don’t really need that element of air-traffic control of someone standing in front of them: one can do that, of course, but I think it often brings more satisfaction to the audience than it does to the performers. What I enjoyed most were those intense phases of rehearsal and learning to be one: to breathe and phrase as one, and take the material from one another and give it back in that seamless fashion. That’s one of the most fulfilling aspects of our work for me.

Has your perspective on Mozart shifted since your last recordings of his music around a decade ago?

Definitely. The relationship with Mozart as a whole has been very complicated for me since childhood, but I feel I’m very slowly but surely getting there. Of course your relationship with a composer and with certain pieces is constantly evolving, and I think what’s interesting is that that happens even if you’re not actively engaged with pieces. Even if you rest and let them be, when you come back to them you have to reacquaint yourself: you can’t just pick up where you left off, and I don’t think it’s healthy to do that either. You have to make new decisions - re-examine everything, dismantle it, pick it apart and reconsider everything anew, and that’s what really interests me.

Do you have strong feelings about what sort of instrument you use to play Mozart?

Not so much for these particular pieces, but I did have an experience a few years ago which was absolutely revelatory for me in that respect. I was in Paris for a couple of days in the middle of a European tour after a date at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, and rather than moving on to the next destination and hanging around there for three hours I decided to stay in Paris and practise at the radio house - I was lucky to have access to a studio that had a piano, a fortepiano and a harpsichord in the same space. At the time I was working on the Bach Italian Concerto amongst other things, and I found myself moving from the piano to the harpsichord, and then going over to the fortepiano with some Schubert and the Mozart F major Sonata.

I found the experience mind-boggling, because everything felt so much more natural and easy on the fortepiano, and when I came to the Bach on the harpsichord there was a real ‘before-and-after’ moment. I think that’s when I first realised in a physical way that expression in this music is not between the notes: it’s on the notes, because there’s nothing you can do with the sound per se on a harpsichord in between. The sound is what it is when you touch the key, and I found this realisation incredibly useful because it helped me see how the possibilities of a modern piano (magnificent as they are) can sometimes be counterproductive when you play this repertoire. I will never forget that afternoon: it was definitely one of those pivotal moments where you come out different than when you went in.

How have you felt about being away from the concert-platform and the rigours of touring over the past ten months?

There’ve been a lot of emotions in the mix. I think the one thing that got to everybody the most in the end was the uncertainty: anyone can deal with a situation when you know it’s going to last for two, three or even six months, but the problem is when it drags on like this. There was a certain element of distraction for me, because we were moving from one coast to the other – that wasn’t particularly fulfilling, but it had to be done! I had no access to a piano for quite a while over that period because all the restrictions around non-essential professions impacted the removal workers - but fortunately I’ve always practised away from the instrument as much as at the instrument, so that side of things wasn’t really impeded.

In terms of artistic work, much of that was on hold during that relocation, and because we’re so used to being overscheduled and in action-mode it was very difficult to find this groove of just being. I think so many of us have a tendency to expend our mental energy on projecting ourselves into the immediate and even the long-term future, which runs counter to the principles of Zen: being fully in the moment is so hard for human beings to do anyway, let alone at a time as turbulent as this.

But there’s always something that can happen in the moment, and that can involve reconnecting with things that you never have enough time for in normal circumstances: of course being able to focus on the animals [Grimaud founded the Wolf Conservation Center in 1999] without constant travelling has been a breath of fresh air, but I almost feel guilty for even saying that. This period has been so awful and traumatic for so many people – there have been huge amounts of suffering that we aren’t even aware of, so talk of anything that looks like a silver lining sometimes feels a little inappropriate.

One other thing I've found is that practising pieces that aren’t anywhere on your upcoming programmes is such a different experience from practising with a goal and a certain time-frame in mind: there’s something beautiful about just putting a score on the piano and playing it for the sake of playing it, without any higher goal or purpose whatsoever.

Hélène Grimaud (piano), Camerata Salzburg

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Sergey Yakovenko & Ilya Scheps

Available Formats: 2 CDs, MP3, FLAC

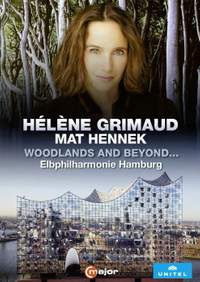

A multimedia concert project with photograph Mat Hennek, filmed at the Grand Hall of Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie

Available Format: DVD Video

A multimedia concert project with photograph Mat Hennek, filmed at the Grand Hall of Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie

Available Format: Blu-ray