Interview,

David Temple on seasonal Britten

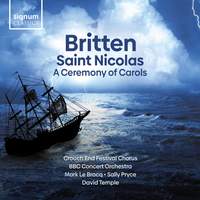

Britten's A Ceremony of Carols and Saint Nicolas are both, under normal conditions, staples of the Christmas concert lineup for choirs around the world - the former a sequence of medieval texts for the Christmas season, the latter a community-oratorio dramatising the life of the fourth-century saint who would eventually evolve into today's secular Father Christmas.

Britten's A Ceremony of Carols and Saint Nicolas are both, under normal conditions, staples of the Christmas concert lineup for choirs around the world - the former a sequence of medieval texts for the Christmas season, the latter a community-oratorio dramatising the life of the fourth-century saint who would eventually evolve into today's secular Father Christmas.

While Christmas musicmaking is somewhat muted this year, happily the new recording of these two works by Crouch End Festival Chorus under David Temple (recently created an MBE for his services to music) is anything but – somehow capturing the unashamedly 'amateur' spirit of these works while avoiding sounding amateurish.

I spoke to David about how he managed that seemingly paradoxical feat, and about the background to these two works – as well as a little peek ahead into the choir's future plans.

Given that Britten’s vision in Saint Nicolas was of a work that would be performed by amateur musicians, how did you strike the balance between polishing the performance and retaining the rough-around-the-edges feel that Britten seems to have prized?

There have been plenty of pieces written for amateur choirs - The Dream of Gerontius, Belshazzar’s Feast, the War Requiem, A Sea Symphony and so on. Having amateur singers is more common than not. But I suppose the key difference here is that Saint Nicolas was that it was intended as a community event. One of the problems I have with many of the recordings that exist at the moment is that they are so superbly polished – which I am not against, but I am looking for something more! In a way you almost lose the essence of what the piece is really about. What I wanted to introduce particularly was the concept of “performance foremost, precision to follow”. That’s not to say that when you listen to this performance it isn’t precise – there’s all sorts of details in there which I don’t hear on other recordings – but my prime concern was to produce something that would make people sit up and really feel like they were part of the performance themselves.

How much of a precedent was there for “community oratorios” of this kind in Britten’s time, written specifically for amateurs to tackle?

Holst wrote some pieces for the St Paul’s Girls’ School, and Tippett wrote some for Morley College, so it’s something that I think was becoming more common throughout the twentieth century. On my recording, one of the things that really mattered to me was having what I’d call natural children’s voices. I love the sound of King’s College and St John’s College and that sort of thing, but I also like to go into a primary school and hear the kids singing with no tuition at all. Hopefully what we’ve got on our recording is the sound of a very well-trained primary school choir. The children who sing the Pickled Boys in particular.

The little boy who sings the role of the boy Nicolas (which the score specifies should be sung by the youngest treble in the choir!) I don’t think had ever sung a solo in his life; and when I first visited the school, I went down the row of children asking them each to sing the line. And when this boy sang it I just got goosebumps from his singing, it was wonderful. When we did the recording, of course, he had to do it a lot of times because of all the takes we were doing, and it was spot-on every time.

Is there any evidence that Britten’s experience of the crossing the Atlantic while composing Saint Nicolas fed into the depiction of the storm and the fearful sailors in the fourth movement?

St Nicolas was actually written several years after that crossing, in 1947 for a performance in 1948. The Ceremony and the Hymn to St Cecilia were the ones he wrote while on board ship in 1942. But that being said, I do still think that his being on ship for four weeks and being a bit scared – not just of the waves but of the U-boats – must have really affected him, and when he came to write St Nicolas a few years later, I’m sure he had all of that in his mind.

The version of A Ceremony of Carols performed here – in twelve movements – is the one that has become standard and is widely used. But it isn’t actually the original - That yongë child and the harp-only interlude were added later. Why do you think Britten revised it into the form we know now?

The score lists a movement 4a and a movement 4b, so at some point Britten must have renumbered everything. I think there are probably two reasons for this; one is that That yongë child is one of the most beautiful things Britten ever wrote, and so when he added that to the Ceremony it really enhances it. But also, while he was on board ship, in addition to being rather scared he must also have been very bored! One of the things he had with him was a book about how to play the harp, and he must have treated it like a new toy. The Tchaikovsky-like harp sound we imagine, of rippling glissandi and arpeggios, is something that he features less and favours the use of harmonics and the very low notes of the instrument. It’s sensational harp-writing, beautifully played on our recording by Sally Pryce. There’s an element of Mahler in it, actually; Britten was a great fan of Mahler’s music long before Mahler was really well-known, and that lovely harp part in the Adagietto of the Fifth Symphony is very much in this vein.

It’s thought that Britten was preparing to compose a harp concerto at around the same time as working on A Ceremony of Carols; is there any indication that this found its way into the prominent, and often taxing, harp part for the Ceremony?

I don’t think he actually got very far with the concerto – it was intended for the harpist of the Philadelphia Orchestra during his stay in America. Looking at the writing for the harp in the Ceremony, I can’t imagine any of it fitting in with an orchestral score. It’s so delicate and so obviously solo writing. He also uses the theme from the Procession, the opening movement. I think it must have just got his brain ticking over as to how he could write something really interesting for this beautiful instrument. It’s much more the concept of the harp that he transferred from his work on the concerto, rather than any specific motif or anything like that.

Thinking about the other movements, although we’ve spoken about That yongë child and indeed the harp’s solo Interlude as some of the best, I also think that There is no rose bears mention; it just takes my breath away. Frankly I don’t think there’s a dud note in the entire piece – like Messiah in fact, where there’s hardly a single movement that falls short. For some time I used to think that Lift up your heads was a slight weak point, but I decided to really put some thought into making it come alive, and now it’s one of my favourite movements. And I did something similar with St Nicolas - the penultimate movement, where the choir is just singing about his life. It’s perhaps not obviously quite as vibrant as the rest of the piece. So we worked very hard on it, and it’s probably the track I’m most proud of on the whole album. It can sound a little bit foursquare, but what I tried to do is to give each part the licence to have their own character when they have a particular snippet of the story. So I’d encourage the tenors to become rough farmers for one part, for instance, with a very vivid image in their head.

Possibly the greatest music in the whole of St Nicolas is the final movement, which has echoes of the War Requiem to come and The Dream of Gerontius that came before it – the way he uses the layers. The way Britten uses the Nunc Dimittis chant is quite similar to Noe from the waters in a saving home… from Gerontius. Even though there are some connections between Britten and Elgar – he did conduct Gerontius at one stage, I believe – he was trying to look beyond the English choral-society tradition of George Dyson, Vaughan Williams and perhaps even Holst. The instrumental writing is very striking – in the song about the birth of Nicolas the pianos are playing and the strings are doing all kind of left-hand pizzicatos and you’d swear that there was a harp in there. The combination of the piano and the strings gives that impression very strongly – so the perfection of Britten’s craft allows him to get more out of the orchestra than is actually there!

Crouch End Festival Chorus has been combining familiar favourites with lesser-known repertoire in its most recent recordings – reviving the tradition of large-scale English-language performances of Bach’s St John Passion as well as singing on world-premiere recordings of Parry and Rosner. Can you tell us anything about your future plans with the choir?

The way the choir exists is that we do both our own promotions and also hire ourselves out to others. The Parry and Rosner recordings were ones where we were brought in to sing on those recordings; the other projects are ones that we generate ourselves. In terms of the future of the choir I’m delighted to say – though I can’t reveal too much – that we have two projects lined up for Chandos Records and two for Signum Records; considering we’re in the middle of this musical depression, it’s something fantastic to look forward to.

The one that’s likely to come first will be a South American-themed recording for Signum where we record a piece by James McCarthy called 17 Days, which is about the 2010 Chilean mining accident. This was a work we commissioned and it went down an absolute storm. There’s also a brand-new piece – it’s not even been rehearsed yet – which is a Tango Mass by Augusto Arias. The whole theme is South American. I have form for this myself, in terms of discovering Mass settings –Will Todd’s Mass in Blue was commissioned by my Hertfordshire Chorus. We premiered that in 2003 and it’s had hundreds of performances since. Let’s hope it’s not too long before we can get these recordings made!

BBC Concert Orchestra, David Temple, Crouch End Festival Chorus

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Sarah Fox (soprano), Kathryn Rudge (mezzo-soprano), Toby Spence (tenor), Henry Waddington (bass-baritone), Crouch End Festival Chorus, London Mozart Players, William Vann

Available Formats: 2 SACDs, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Sophie Bevan (soprano), Robin Blaze (countertenor), Benjamin Hulett (tenor), Robert Murray (Evangelist), Andrew Ashwin (Pilate, Peter), Neal Davies (bass-baritone), Ashley Riches (Jesus) & Peter Jaekel (organ), Crouch End Festival Chorus & Bach Camerata, David Temple

Available Formats: 2 SACDs, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

London Philharmonic Orchestra, Nick Palmer

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC