Interview,

Elīna Garanča on Schumann and Brahms

The Latvian mezzo Elīna Garanča’s rise to fame after her appearance in the final of Cardiff Singer of the World in 2001 more or less coincided with the beginning of my own passion for lieder, and for the past twenty years I’ve been hoping she might one day release a recording of the Brahms songs which featured on her programme in the preliminary rounds of the competition. My wish was granted earlier this month in the shape of a glorious recital centring on Schumann’s Frauenliebe und -leben with Scottish pianist Malcolm Martineau, so it was a particular pleasure to speak to her about her childhood exposure to this music, her preparations to make her first foray into Wagner (COVID restrictions permitting) in April, and the roles which might figure in her long-term future…

The Latvian mezzo Elīna Garanča’s rise to fame after her appearance in the final of Cardiff Singer of the World in 2001 more or less coincided with the beginning of my own passion for lieder, and for the past twenty years I’ve been hoping she might one day release a recording of the Brahms songs which featured on her programme in the preliminary rounds of the competition. My wish was granted earlier this month in the shape of a glorious recital centring on Schumann’s Frauenliebe und -leben with Scottish pianist Malcolm Martineau, so it was a particular pleasure to speak to her about her childhood exposure to this music, her preparations to make her first foray into Wagner (COVID restrictions permitting) in April, and the roles which might figure in her long-term future…

This is your first lieder recital on record – did it come about in response to lockdown restrictions, or were the plans in place before that?

We’d already decided to record the programme before lockdown; the restrictions just pushed it forward a little! Until now it’s never felt like the right time to record something like this, but I’ve been singing lieder for many years - I have eight or nine different recital-programmes, including songs by Rossini, Bellini and Verdi as well as Russian, Spanish and German repertoire. But I always knew that my first recital recording would centre on Schumann’s Frauenliebe: that was a done deal for me from the beginning. I wanted to create a programme that included plenty of contrasts whilst staying within one period, so Brahms seemed like the ideal coupling for Schumann. They both work extremely well for the mezzo voice, and yet their vocal writing is so different: Schumann lets the voice be the carrier of the music, whereas in Brahms the voice is the boat and the piano is the river! And Brahms songs like ‘Alte Liebe’, ‘Heimweh’, and ‘Von ewiger Liebe’ are pieces that have been with me for some time – I sang those last two a lot in competitions right at the beginning of my career, so it’s fun to come back and make a statement on them nearly twenty years later.

It’s also your first recording with Malcolm Martineau – how did your partnership come about, and what attracted you to one another?

What I love about collaborating with Malcolm is that we both see music in pictures, and talk about it in the same visual terms: if I say something like ‘At the beginning of this song I see a cold, rough November sea’, he knows what I mean immediately and can translate it directly into sound, which is quite an extraordinary gift! We started working together four or five years ago, perhaps even a little longer. I’d been switching between several pianists for a while, and I’d got to the stage where I thought it would be nice to have just one person who really ‘gets’ you. I’d noticed that a lot of my colleagues had been performing with Malcolm, and I instantly liked his energy; when we first met we sat down in a hall and played through some repertoire together, just to get a sense of how we click and who we are, and he completely gave himself over to me from the very beginning. But on the other hand, if he feels strongly about something he says it, and that’s so important in a Lieder partnership – you don’t want someone who just blithely goes along with whatever you suggest. He also has a certain politeness and discretion which strike me as very British, and I appreciate that side of his personality very much!

Who were your early inspirations in lieder?

A lot of my feeling for song repertoire has come automatically, especially in the Schumann: my mother was a singer, so as a child I was around while she was singing these songs as well as Schubert, Brahms, de Falla, Mahler and Strauss, and that was actually the first music I heard in my own surroundings. My father was a choir conductor, so there was also a lot of sacred music at home – that’s what I heard growing up, much more than opera and symphonic music. My parents couldn’t leave my brother and me at home while they were working, so sitting in on rehearsals and concerts was just our normal reality, but with time I came to understand what a wonderful artist my mother was and became incredibly proud of her. So lieder was always in my blood; I learned so much from hearing different pianists working with my mother, and I still have her markings in a lot of my scores. It’s been part of my life from the very beginning.

I did study song repertoire more formally later on – the first half of my diploma exam in Latvia was lied, and the second half was opera arias with orchestra. Of course you’re always gaining new insights from watching your colleagues, and then there are those interpretative shifts that come simply through your own life experience. These days I certainly sing something like Brahms’s ‘Heimweh’ with less melancholy and sadness than when I was younger: it’s something to do with gradually losing your fear of mortality as you get older, and looking back on certain events and emotions in your life with a sort of resolution and release rather than with frustration and despair.

And has your perspective on the Schumann cycle also shifted over the years?

I don’t think that my personal perspective has changed all that much, although singing these songs becomes a much more realistic experience at my age when you can turn the page back and revisit how you felt at those pivotal moments in your own life. What has changed quite recently, though, is the wider perception of Frauenliebe, and that increasing negativity is something I really push back against. I often hear the argument that this cycle is no longer viable in the wake of the #MeToo movement and women’s continuing struggle for equality and independence, because the texts reduce the woman to a very submissive role, but I couldn’t disagree more: the idea of surrendering the self is something that crops up time and again in Romantic poetry, and it has nothing to do with the primary contact between a man and a woman. Unfortunately a lot of people don’t understand that any more and interpret the cycle on a very superficial level, but from where I’m standing it operates on a different plane altogether. I feel very defensive when people say that they find the texts ridiculous, because I find them absolutely glorious and beautiful.

Speaking of characters who surrender the self, you’re currently preparing to make your debut as Kundry in Parsifal: how are you feeling about taking that first step into Wagner?

Kundry’s actually going very well: I have a lot of Strauss experience under my belt after singing Rosenkavalier for seventeen years, so sprechgesang is something that I know how to do. Wagner obviously requires a different physical approach to Strauss, but having worked on it with my teacher I still maintain that the most complicated and challenging music to sing is bel canto because it requires such an enormous spectrum of technical refinements. Sure, Wagner is challenging in terms of stamina, but it’s a more straightforward way of communication which doesn’t require the artificial finesse that you need in bel canto: if you come to Wagner’s music having been used to singing that repertoire, sometimes it feels that you’re not doing anything other than making noise! But what you do need to realise in Wagner is that the voice is an instrument - often not even the main instrument - so you have to switch your perspective and become a part of his musical universe rather than imposing yourself upon it. For me that’s the most challenging thing: just allowing yourself to be one colour in the overall picture, instead of focusing on producing an immaculate pianissimo or filato or diminuendo!

My dream was always to go into dramatic repertoire and tackle the bad girls and the big mammas! When I was a young singer I always hoped that Amneris would be my ultimate goal, and also my finishing-line: I started out singing baroque and bel canto roles, and Wagner really seemed like another universe. But over time your technique and your body change, and when you’re singing Dorabella in Così fan tutte for the eighteenth time you start to think hard about what else you can do as an artist. Once I’ve made that transition into Wagner, though, there will really be nothing more that I can squeeze out of myself as a performer and a vocalist: starting with baroque repertoire and finishing with Parsifal covers the entire rainbow!

How are things looking for that debut in terms of lockdown restrictions?

It’s scheduled for Vienna in April, with Jonas Kaufmann as Parsifal, Ludovic Tézier as Amfortas, and Georg Zeppenfeld as Gurnemanz. I’m very optimistic that it will happen, despite all the current uncertainty; if people stay focused and stick to the rules over the next few months then hopefully we’ll all be in a better place by the spring, and the Vienna State Opera is doing everything in its power to make the production work. Our stage director Kirill Serebrennikov is locked down in Moscow at the moment, but he’ll be working with us remotely and via an assistant in Vienna; he and I have a video-call scheduled in a couple of weeks’ time to talk about how we both see Kundry and what sort of vision he has for this production. If we can bring this off at Easter as planned, I think this particular piece will have a very direct emotional impact on people after the events of this year: fingers crossed.

Beyond Kundry, what else is on your bucket-list in terms of potential future opera roles?

Well, I still haven’t climbed my Mount Everest, Amneris …I’d also love to do the Principessa de Bouillon in Adriana Lecouvreur, and once I’ve reached the age where I can credibly play the mother of the tenor, I think Azucena in Il trovatore will be a very good role for me. Things like Klytaemnestra and Ortrud could be on the table too further down the line, but as long as I can present a relatively youthful image on stage I’m going to roll with that: voices and appearances age quickly enough on their own, so I want to continue singing so-called 'young' roles as long as I can!

One other thing I’m toying with is the idea of being Mistress Quickly one day, and having a steamy affair with Falstaff - why not?! I like humour, and I so rarely get to do comic roles on stage. I do love the opera, but those scenes with the four women together can become a bit corny if the director doesn’t find a way to make the dynamics between them interesting. Quickly can have a sexy aura around her and be hiding that from Alice and Meg, which I think could put quite a different slant on things! Let’s see…

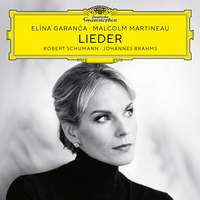

Elīna Garanča (mezzo), Malcolm Martineau (piano)

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC