Interview,

Joan Enric Lluna on Rodrigo

The Spanish composer Joaquín Rodrigo is, perhaps inevitably, regarded as something approaching a "one-hit wonder", with his eternally popular Concierto di Aranjuez by far his best-known work. Conductor Joan Enric Lluna has made it his mission to redress the balance by bringing Rodrigo's numerous other works to a wider audience, and in doing so illustrating the composer's own mission - little short of a complete rebirth of a truly Spanish form of classical music.

The Spanish composer Joaquín Rodrigo is, perhaps inevitably, regarded as something approaching a "one-hit wonder", with his eternally popular Concierto di Aranjuez by far his best-known work. Conductor Joan Enric Lluna has made it his mission to redress the balance by bringing Rodrigo's numerous other works to a wider audience, and in doing so illustrating the composer's own mission - little short of a complete rebirth of a truly Spanish form of classical music.

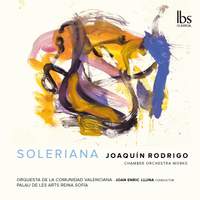

I spoke to Joan about his new album with the Orquesta de la Comunitat Valenciana, which showcases Rodrigo's glorious orchestral works.

As you’ve alluded to in your notes, it’s virtually impossible to discuss Rodrigo without mentioning the Concierto di Aranjuez. Given his considerable output, how did this one single piece come to dominate his reputation so heavily?

In my view, Aranjuez has become in many ways “the guitar concerto”, it has captivated audiences around the world by its great beauty, and at the same time it has become one of the big challenges for guitar players, a sort of a compulsory piece for guitarist, a piece to have in their repertoire to be considered a true virtuoso soloist.

In another hand, I think that somehow some pieces of art become iconic. Sometimes it is their symbolism, their meaning, their political attachment. In the case of the Aranjuez concerto it is just pure beauty. Its slow movement’s astonishingly beautiful melody, its melancholic and dreamy mood has made it a popular “song” through generations, it is fantastic! The elegance of its third movement and the flamenco flavour of its first and second movements makes it unique. It is not surprising that it is one of the most performed pieces from a 20th Century composer.

Nevertheless, its success has hidden maestro Rodrigo as a true first league composer, an incredibly inspired musician and an amazingly crafted orchestrator. The works on this CD show many of his qualities as a composer. There is a fascinating maestro Rodrigo beyond the Aranjuez concerto, it should be rediscovered and I am convinced that his orchestral works, in this case for chamber orchestra, will be included in programmes once conductors and promoters are more aware of the quality and beauty of this music. This would be the dream aim of this CD.

Rodrigo subscribed to a philosophy he termed “neocasticismo” – a kind of rediscovery of cultural purity, seeking to identify authentically Spanish artistic expressions and shed foreign elements. How much do you think he achieved this?

When you hear any piece of Rodrigo it is easy to identify his language. He absolutely achieved his goal in my opinion. He embraced both, the background aesthetic ideas of the nationalistic composers like de Falla, Turina or Granados, and the neoclassicism of Stravinsky, Dukas or Poulenc. Nevertheless he created a very personal language, taking inspiration from the Spanish masters of the 15th and 16th centuries. According to him that was the golden age of Spanish Music. Rodrigo admired Cabezón, Millán, Narváez and, of course, Tomás Luís de Victoria. Rodrigo offers tributes to them in a lot of his compositions, using ancient Spanish dances and melodies or inventing other melodies that remind that period. This is what gives Rodrigo’s music its very unique flavor. That is what he means by “neocasticism”, a term that means authentic and genuinely belonging to a place.

Although their approaches to forging a Spanish identity in music were broadly different, Rodrigo and Falla were friends and presumably must have shared ideas; do you hear any echoes of Falla in Rodrigo’s music, or vice versa?

Absolutely. Rodrigo admired Falla, he was his hero. For Rodrigo, Falla was the absolute reference of Spanish Music in the 20th century and the composer that linked new music with popular music, including a few of his pieces that take reference from the golden age of Spanish music, back in Medieval times and Renaissance. You can hear the influence of Falla in Rodrigo, and they became friends and Falla helped him a lot. But we must not forget that Falla was much older, and an important, established composer when they first met in Paris. Rodrigo uses many elements of the Neoclassical and Nationalistic movements, in which Falla and Pedrell were the references in Spain, so he also takes inspiration in Spanish folk music.

The difference is that he doesn’t go to just folk music of different regions of the country, with flamenco as the dominating style (Falla or Granados’ main source of inspiration). He goes deep back in the history of Spanish music, to the 15th and 16th centuries, this is where the personality of Rodrigo’s music recalls. In another hand, we must take into account the fact that Rodrigo was also younger and naturally more experimental than Falla. You can hear that it in the “Villancico” of the present CD, for instance, where he takes the strings into technical limits at times, and in some unexpected dissonances, for instance in the “Tres viejos aires de danza”. In fact, I had to call maestro León Ara, Rodrigo’s son-in-law a few times to make sure that some of the chords in these pieces were not editorial mistakes, but actually written on purpose by the composer to achieve what he wanted, subtle and sometimes shocking harmonic surprises. The pieces that link both composers more clearly are Falla’s harpsichord concerto, where he experimented with more modern sounds and textures and “El retablo de maese Pedro”, where Falla goes back to Medieval music.

Rodrigo’s tendency to draw on the Spanish Baroque for inspiration seems to have a parallel in Vaughan Williams doing the same with the English Tudor period – looking back to a time when the nation’s musical language was maybe less cosmopolitan. Would you say the two composers were trying to achieve broadly the same things?

I believe so, it is possible to find parallelism in both composers. They both find inspiration in 14th, 15th and 16th century music, a period that has a very particular sound to our 21st century ears. The colour of the Medieval and Renaissance music is heard in both composers, the harmonies, the somehow “fragility” of sound texture and the phrasing cadences. An example of this parallelism can be found, for instance, between the “Fantasy on Thomas Tallis” and the “Tres aires viejos de danza”, included in this CD. It doesn’t mean that they sound similar, but you can hear in both pieces this kind of ancient modernized sound flavour. Although they share this way to root some of their music, one important difference is that Rodrigo didn’t write big symphonies. Most of his compositions, with a few exceptions, are written for medium size orchestra, chamber orchestra and, of course for guitar and for voice, he somehow remains more “pure”.

You mention that much of Rodrigo’s early output consisted of arrangements and adaptations of the keyboard sonatas of Antonio Soler (roughly contemporary with Haydn). Why was Soler’s music so important to him?

Rodrigo describes Soler’s Sonatas in one of his own writings as “delicious pieces”. In these Sonatas, Padre Soler uses ancient Spanish dances, and I believe that this fact attracted Rodrigo’s attention. It is very interesting to read in his book of thoughts and writings that when he played Soler’s Sonatas he could hear inside his head a hall world of orchestral sounds implicit in the music, so it means that he already had the orchestration in his mind when playing them on the harpsichord or the piano. He later says that in Soleriana, “the naive harpsichord of Padre Soler is protected and covered of original orchestral clinks that do not alter the original authentic ancient Spanish music, forming a complete unity with ancient flavor and modern physiognomy”. This tells us a lot about Rodrigo’s aesthetic ideas. As he says, he wants to give a new life to this wonderful old music. I think that this idea helps a lot to understand his music and, on top of that, I think that Soleriana is a good example where to admire his mastery in orchestration.

Compared with other flowerings of European musical nationalism such as those occurring in Central Europe, Spain’s position was quite different – an independent state, rather than one ruled by foreign powers and needing to assert its cultural identity. Given this, what do you think gave rise to the nationalist grouping that he, Falla and Albeniz seem to form?

Albéniz, the first composer of that generation that succeeded in Paris found his own language, after some years of Romanticism, in rooting his music in his own country’s folklore. Falla, Granados, Turina and other artists followed and formed a unique group of incredibly talented composers. At that time, some intellectuals and artists had the possibility of studying with the best teachers at the time, mainly in Paris. They learned the technique of composition form Dukas, Boulanger, etc., and put it together with a fantastic inspiration based on their own country’s popular music. The basic aim was to make the amazing rich Spanish popular music into a universal language that could be understood around the world. They, therefore, created a unique musical language that has been very successful ever since because it added to the music world something new and authentic.

It is also worth mentioning that some of these musicians, together with other intellectuals and artists, as García Lorca, Picasso or Dalí, coincided in time and place for some years with the second Spanish Republic at the “Residencia de estudiantes”, a university students residence hall where the best ideas and pieces of art flourished in what could be described as the (other) golden age of Spanish music. Unfortunately the Civil War and the subsequent dictatorship destroyed all that. Most artists had to go in exile, even Falla, who was not politically inclined to any side went in exile just after the civil war away to Argentina, because he found in the country “too much noise”, referring to political pressure. Rodrigo stayed. He was younger and had the physical condition of being blind, he managed to obtain a scholarship to study in Paris thanks to Falla, and worked after that through the most difficult years of post-war. He actually not only survived, but made it possible to have a big career since the Aranjuez Concerto’s success, and admirable story.

I would also like to mention that, after having talked about exiled composers, there is a lot of fantastic music being rediscovered by composers that went in exile. Most of them followed Falla’s path, which seemed to have been the natural way Spanish music could have developed: Bautista, Halffter, Bacarisse, Bal y Gay…. Rodrigo was in fact one of the few exceptions of staying in the country and developing a career.

I have been active rediscovering music by these composers and recorded a few CDs, some for clarinet, the last one, dedicated to Bacarisse, with my group Moonwinds. Discovering this repertoire has redeemed myself with my country’s music history, discovering the enormous potential that was left behind because of the dictatorship.

Orquestra de la Comunitat Valenciana, Joan Enric Lluna

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC