Interview,

Antoine Tamestit on Bach

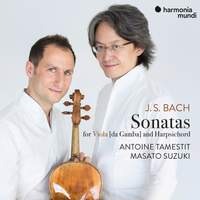

It’s hardly rare for Bach’s instrumental works to be arranged for new forces – sometimes authentically (even by the composer himself), sometimes less so. One instrument that doesn’t often get a share of the action is the viola, but Antoine Tamestit and Masato Suzuki are out to change this with their new album. Not only do they present Bach’s three sonatas for viola da gamba in a new guise (and one that, as Tamestit argues, could very well have existed in the composer’s own time) but they also showcase a wholly unique instrument: the magnificent Mahler Stradivari viola, one of only thirteen extant violas by the legendary luthier and endowed with a number of characteristic qualities that make it truly distinctive.

It’s hardly rare for Bach’s instrumental works to be arranged for new forces – sometimes authentically (even by the composer himself), sometimes less so. One instrument that doesn’t often get a share of the action is the viola, but Antoine Tamestit and Masato Suzuki are out to change this with their new album. Not only do they present Bach’s three sonatas for viola da gamba in a new guise (and one that, as Tamestit argues, could very well have existed in the composer’s own time) but they also showcase a wholly unique instrument: the magnificent Mahler Stradivari viola, one of only thirteen extant violas by the legendary luthier and endowed with a number of characteristic qualities that make it truly distinctive.

I spoke to Antoine about this fascinating instrument – part museum-piece, part living history – and about the sometimes fluid relationship between music and instrumentation in Bach’s output.

In your recent article in The Strad you mentioned being forewarned by other players that the 'Mahler Stradivari' would be a difficult beast to tame. How different is it from other violas you’ve played?

At the beginning I felt that it was very difficult to play, yes. The main reason for that was that it had been in and out of storage for many years: it would be loaned out for short periods and then go back in the safe or collection. It’s quite difficult to research its history thoroughly, but we are fairly certain that there was a long period in the nineteenth century (probably a few decades, maybe even a hundred years) where the instrument was not played at all. it’s a very interesting combination: on the one hand it’s an old instrument that felt a little bit closed-up by being locked away for so long, but it was also a little like a new instrument that had not bloomed yet and was still green in a way, which was very unexpected for a 400-year-old viola.

Early in my relationship with the instrument, I met with some very important viola-players (including my previous teachers Tabea Zimmermann and Jesse Levine and others like Yuri Bashmet and Nobuko Imai), who all agreed that it was closed-up and difficult to play at the moment - but all of them also felt that there it had such wonderful potential and a particular colour that was very special, and that if I could I should simply be patient. So that’s what I did, and I felt that colour and potential too. With all old instruments, they have been played by many different people who’ve shaped them in different ways, so you have to get used to them and understand how they need to be played – but for me in this particular case it was also about trying to ‘wake up’ the instrument and bring out its best qualities. It certainly wasn’t an easy task, but I could feel that underneath it all there was something wonderful. Every instrument of course is unique in its way, but this instrument was built by Stradivarius on a truly unique mould that makes it very different from his other violas, and from other violas in general. It’s flatter and wider, but it’s not that long; it also has a poplar back that emphasises lower harmonics and lower sound, so it has a very particular colour that takes time to locate. But once I did, it was quite incredible: I feel that I’m able to play any repertoire from the baroque to the contemporary on the instrument and it reacts.

What’s it like travelling around the world knowing that the instrument you’ve got with you is not just the tool that you use to make you music but also this incredibly valuable antique that can’t be replaced?

Yes, it’s exactly as you say: most of the time I try to remember that this is the tool that I need to work, whilst taking into consideration that it’s a very valuable and also a very old instrument that needs extremely special care. In terms of its safety, I keep it very close to me on planes and trains, and when I’m walking around it’s always on my back – in fact if I don’t have anything on my back now I feel I’m missing something! But I try not to think that I have the equivalent of an Leonardo da Vinci painting strapped to me, otherwise I wouldn’t be able to move! My philosophy is that if something happens to it, it’s already a very well-recorded instrument – everybody knows how it is, what it is, how it looks - but of course I’m always very careful with things like humidity and temperature. I check in with it each day to see how it’s doing: that can involve cleaning the instrument, examining the wood, making sure that nothing’s opening up in terms of the glue that holds the wood together…kind of an every-day health-check, really!

The name of Carl Friedrich Abel seems to recur in the story of Bach’s writing for the gamba. Is there any evidence that any of these works were written specifically for him (as other composers would subsequently do with particular instrumentalists)?

We don’t know exactly, but we do know that the First Sonata (BWV 1029) was initially written for two flutes and continuo, and then it seems that Bach wrote quickly an arrangement for viola da gamba and harpsichord (possibly for this Abel fellow and himself to play in a concert). What we have is two separate parts, not even a score, so it definitely feels like these were prepared for performance. This is the only sonata for which we have a manuscript in Bach’s hand; for the others there are only manuscripts by his student Christian Friedrich Penzel, which are clearly for viola da gamba.

I always start from the assumption that transcription was actually something very common at the time: you’d play the pieces with whichever instrument(s) you had in front of you, or within the orchestra or town that you were visiting. Perhaps some musician friends visited, and you made a new arrangement for them to play together…and all of this was OK. Today we are very careful, and I include myself in that: I consider these pieces holy works, and I want to see every version, every annotation, but still I think it’s legitimate to play them on any instrument, because that’s how it used to be.

How much work did you have to do to make these works performable on the viola?

If you look just at the notes, they can be played almost exactly as they are: you might have to change a total of four or five notes across all three sonatas. So that's how I started out, but I couldn’t help being inspired by actual viola da gamba playing and the da gamba sound: somehow in the medium register (which is the G string for the viola, so that’s getting close to the low register), the da gamba sounds more brilliant and slightly more nasal than a modern viola. So I took it upon myself to make my own arrangements - not only to solve those five notes I was talking about, but also to take certain lines up an octave so it sounded closer to the brilliance and the special sound of the viola da gamba. Again you can see that that was also the practice of the time: in the original version of the first sonata for two flutes and continuo, the notes are the same as in the viola da gamba version but at different octaves. When you talk to harpsichord-players like Masato Suzuki or anybody who does a lot of cantatas or Passions, they will tell you that playing things up an octave was also a type of habit during this period: musicians instinctively knew when to do it depending on the hall or maybe on the instruments at their disposal, so I also took a little bit of liberty by considering that this liberty was also being taken in Bach's time!

You’ve played quite a lot of Bach on this instrument before – do you find it suits his music particularly well?

Yes: I was always attracted to Bach since I was a child, but when I received this instrument and started to play his music on it, it felt so comfortable and so full. It felt exactly right for this repertoire – even more so when tuned at 415, and still more so with gut strings (or even naked gut-strings) and with a baroque bow. I can’t be certain, but it seems like the viola was built for this lower tuning and it feels at home at that pitch: it works beautifully not just for Bach, but also for Telemann and other baroque (or even Classical) composers.

Antoine Tamestit (viola), Masato Suzuki (harpischord)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Antoine Tamestit (viola)

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC